Summary of Parmigianino

With the possible exception of his nemesis Correggio, Parmigianino was the leading painter of Palma; an eccentric, but technically adept virtuoso who also worked in Rome and Bologna. He ranks as one of the most compelling artists, showing a true artistic daring in a readiness to confront the orthodoxies of the day and a leading exponent of the exaggerated Mannerist style. Defying the naturalistic approach of the great masters of the High Renaissance (namely Leonardo, Michelangelo and Raphael) some have viewed the rhythmic sensuality of his figures as an effort to translate the feeling of spiritual uncertainty that was a by-product of this most turbulent period of Italian history. His was, however, a short career (Parmigianino died in his thirties) but in that time he produced a substantial body of work featuring drawings and paintings of the profane and the sacred, often tinged with a feel for ethereal and the erotic.

Accomplishments

- Seen as a brilliant exponent of the Mannerist style, Parmigianino's works was notable for the freedom of his brushstrokes, his elegant decorative schemes, and a subtle rendering of spatial incongruity and elongated human figures. He was drawn to the idea of the super-natural, rather than the natural, but his art managed the fine balancing act between expressive splendor and technical control.

- The perception of Parmigianino as an eccentric is based on his pursuit, in his later life especially, of magic and alchemy. This translates to his paintings which are often lit from uncertain sources, giving the impression that the paintings themselves carry a golden glowing light that emits from somewhere within the subject. Moreover, his chiaroscuro and innovations in drawing reveal his fascination with transfigurations from one form of matter into another. However, his creativity was born of a mysterious, restless mind that meant that any full realization of his vision would always elude him.

- While other Mannerists tried to exaggerate the idea of beauty as presented by Raphael and the other masters of the High Renaissance, many of Parmigianino's paintings contain formal ambiguities that seem to verge on a sense of distortion. He would often apply a vivid use of color to create an impression of tension within the picture frame, while his figures, both portraits, and characters within religious scenes, are often imbued with a rather daring sensuality.

- Part of Parmigianino's legacy was his incursion into the field of printmaking. The feature of graceful elegance in his painting transferred in fact to Parmigianino's drawings. Indeed, he was one of the first Italian painters to venture into etching, using the etching needle with the same (if not more) freedom he used with his pen. He would use etchings to reproduce earlier drawings creating high demand for his graphic work both domestically and abroad.

Important Art by Parmigianino

Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror

Parmigianino's earliest self-portrait - casually (but unjustly) dismissed by Renaissance historian Cecil Gould as "a witty visual conceit, typical of its century" - was a meticulous and radical composition using a curved mirror from a barber's studio; the painter carefully copying everything visible in the glass onto a convex panel of poplar wood he made specifically for the purpose.

In their attempt to step out from the long shadow cast by the masters of the High Renaissance, the Mannerists challenge the idea of compositional harmony and were intent rather on exploring different perspectives and unusual spatial relations within the frame. Here, for instance, the drawing hand swings and flexes through the foreground of the globed composition, making it appear large and domineering, whilst the angelic delicacy of the boy-artist's face is allowed to recede into a kind of calm power in the mid-ground. Parmigianino's meticulous eye is evident at this early stage in details like the wood-panelling in the roof, the diamond-hatch leading of the window design, the frost or dust on the pane, and the play of light on the boy's ring (betraying an early glimmer, perhaps, of his later obsession with gold and alchemy). The entire picture is lit by daylight originating from the window in the back-left, but then reflected from the mirror-surface back onto the boy's hand and face. In this sense, the painter seems to be lit supernaturally, or from within. Or, equally, the effect is as though he is lit by something beyond the frame, on the spectator's side of the frame. The boards and panels and doorways of the artist's home in Parma are visible in the background even as they seem to shy away in the distorted frame (the Renaissance painters, incidentally, had used mirrors as a tool for eradicating distortions), giving them a demur, intimate feel.

The historian Sydney J. Freedberg calls the picture a "bizarria", albeit one achieved through meticulous "realism". For him, the "gentleness and unaffected grace" of the painter's expression is a necessary offset for the "capricious and bizarre" method of composition, so that the whole harmonizes in a way that is strangely true to High Renaissance ideals even whilst totally rejecting them in a Mannerist trompe-l'oeil.

The painting's fame was endorsed by the American poet John Ashbery whose long poem, Self Portrait in a Convex Mirror was the title poem for a collection that earned him a Pulitzer Prize, a National Book Award and a National Book Critic's Circle Award in 1976. The poem, considered by many to be Ashbery's best, and from which the following excerpt is taken, is a mediation on Parmigianino's painting:

The glass chose to reflect only what he saw

Which was enough for his purpose: his image

Glazed, embalmed, projected at 180-degree angle.

The time of day or the density of the light

Adhering to the face keeps it

Lively and intact in a recurring wave

Of arrival. The soul establishes itself.

But how far can it swim out through our eyes

Oil on convex wood panel - Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria

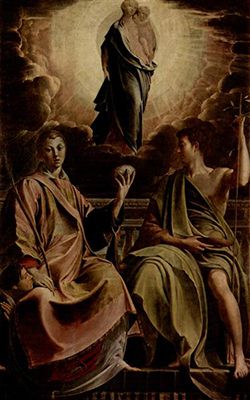

Virgin and Child with Saints John the Baptist and Jerome (Vision of St Jerome)

This is the only altarpiece, for the Caccialupi family chapel Parmigianino was commissioned to make whilst in Rome. One of Parmigianino's most accomplished religious works, it shows John the Baptist gesturing towards a vision of the Madonna as Apocalyptic Woman, cresting from tumbling clouds on a crescent of light. The Christ Child is oddly mature in years, large in size, and knowing in aspect. He, like the Baptist, looks directly at the viewer. He also appears to be selecting the passage from the Book of Revelations in which this scene takes place; an interesting detail of self-reference. The picture mixes different temporal perspectives, the same way it plays with spatial relations between figures: the size of the divine figures are for instance much larger than their distance into the background would suggest.

Parmigianino takes his cue from later ideas of Michelangelo's by sacrificing bodily realism for expressive effect: the contorted pose of the Baptist is physically impossible, designed to enhance the musculature of his shoulders and arms and the elongation of his gesturing finger. His usual attribution of a long cruciform is here simplified to split reeds threaded together. Both Christ and the Virgin take a definitive step forward onto a slab of stone, emphasising their position as bridge between the earthly and the divine. The composition is framed and balanced beautifully, on the left by the Baptist's firmly planted foot and leg, up through his slender cross, and then along the gracefully elongated arm of the Virgin. The right-hand side of the frame is closed nicely by the parallel lines traversed by the Baptist's pointing-arm and the elbow of Jerome. Jerome's red robe balances the palette, gently echoed by the Virgin's loose, translucent slip. Freedberg commented that though "the design may have a quality of drama, the temper of the picture remains controlled and suave." Critics have tended to agree that this painting has sharper acuity and greater precision than much of Parmigianino's later work.

Oil on panel - The National Gallery, London

Mystic Marriage of St Catherine

The "sheer beauty of the execution" of this painting is highlighted by modern critic David Ekserdjian, showing that its power to enthral has remained consistent over centuries - Vasari himself called it a "picture of extraordinary loveliness". It is the second painting that Parmigianino produced during his Bologna period and is therefore executed with an attitude of refreshed self-belief. Indeed, he was considered the chief talent in the city during his residence there.

St Catherine appears with the spiked-wheel that was used during her martyrdom, and here receives a ring from the Christ Child, symbolising her "marriage" to Christ and therefore her chastity. The child gazes into the face of his mother, who is turned with easy grace away from the viewer, her arm lying in postured elegance down by her side. The arm is echoed in the shapely sliver of foot visible beneath her robe, which in turn rhymes with the composition of Joseph's haloed profile in the bottom left. In the centre-background, meanwhile, a rustic doorway frames two shadowy figures.

Gould comments that the Virgin, "looked at through half-shut eyes, seems to resemble a root vegetable", perhaps hoping to suggest something organic about her pictorial composition. It seems much more likely, however, that Parmigianino would not have expected his audience to view his work in this way. The elongated neck seems to have been conceived of rather in the spirit of grace and elegance (or, perhaps, in a mood of mischief if one reads into it a hint of sacred eroticism). Gould proceeds by saying that "the picture hangs together so perfectly that the eye may not immediately perceive subtleties such as the way the green curtain, curving downward, and Saint Catherine's yellow draperies, curving upward, accentuate her alert and intelligent beauty, or how the doorway in the centre of the background frames both the mysterious figures in front of it, and also the central event of the picture - the exchange of the ring." This ring in fact echoes the one in the convex self-portrait, continuing Parmigianino's motif of bejewelling the focal points of his pictures.

Of perhaps most importance is this painting's feeling of liberty and freedom in its brushstrokes, broader and quicker and more impressionistic than High-Renaissance tastes would allow in a Raphael or a Leonardo. Parmigianino, in his confident mature-phase, manages great pictorial harmony whilst also exploring the radical flourishes of the Mannerist sensibility.

Oil on Panel - The National Gallery, London

Madonna dal Collo Longo (Madonna with the Long Neck)

According to Gould, this picture "is Parmigianino's most famous [and] also his most characteristic and most extreme". That a single work can be simultaneously his most 'extreme' and his most 'characteristic' hints at the kind of visionary artist Parmigianino was. The elongated figure of the Madonna is a stunning realization of those two words most often associated with Parmigianino: grace and elegance. The assemblage of the various limbs and their angles in relation to one another is as harmonious as it is erotically charged; and as balanced as it is asymmetrical. The painting certainly garnered the consent of E. H. Gombrich who, in The Story of Art, suggested that his goal, and that of other Mannerists, was to create something "more interesting and unusual" than that of the former generation of Italian masters. Gombrich argued moreover that Parmigianino (as part of the Mannerist movement) might even be grouped amongst the first truly "modern" painters because he "sought to create something new and unexpected, even at the expense of 'natural' beauty [as] established by the great masters".

Gombrich agreed with Gould in the suggestion that the artist's goal was to imbue the Madonna with grace and elegance, and in his attempts to do so, Parmigianino painted her in a "strangely capricious way," with "long delicate fingers" and with an elongated neck "like that of a swan." Other compositional innovations stand out too. The twinning of the planted right leg of the angel in the left foreground with the monumental marble pillar collapses the painting's depth into a narrow and immediate aperture. The elongated and stylised infant Christ stretches across the scene, joining interior and exterior; flesh and the ether. The bottom third of the panel meanwhile seems striped in alternate marble-white and deep-blue, symbolising both the innocence and the royalty of the Divine Mother and Child. The figure of St Jerome and the scroll is relegated to an odd and arresting position, the de Chirico-esque architectural landscape, combined with the fact that the figure (added later) is faded and translucent, and also the fact that a disembodied foot (to the left of St. Jerome) remains from an earlier rendering, gives the painting a somewhat surreal edge.

The painting then retains some of the "violent asymmetry" that Gould observes in its preparatory sketches, and though it might be a radical statement at this point in the history of devotional art, just "One step farther in this same direction", argued Freedberg, and "we should fall either into vapidity or hysteria"). Freedberg's point was that, though highly idiosyncratic, Parmigianino's instincts had known when to kerb his creative indulgences. Gombrich summed it up best perhaps when he said of Madonna dal Collo Longo "if this be madness there must be method in it."

Oil on panel - The Uffizi Gallery, Florence

A Young Woman ("Antea")

Gould called this "Parmigianino's masterpiece in portraiture", commenting on the "intensity of presence that is almost physical". He also points out that this is undoubtably a portrait of the same sitter who appears as the angel nearest to the Madonna in the "long neck" painting, looking directly at the viewer. Perhaps this echo has something to do with the obsessional detail with which the sitter's expression is picked out, and the refined potency of the painting's atmosphere.

Though better known for his radical, Mannerist approach to Religious art, Parmigianino also made great strides in the field of portraiture. The force of expressive presence and decorative detail give this painting a power that was absent from much of the portraiture at the time. As Ekserdjian observes, "her deep brown eyes are open so wide that the whites are completely visible beneath them". 'Antea' refuses to be simply the "object" of this painting, instead gazing back at the spectator with a calm ferocity that asserts her own authority.

Oil on canvas - Capodimonte Museum, Naples, Italy

Choir Vault at Santa Maria della Steccata, Parma

This detail from Parmigianino's work at the Steccata, showing the 'Wise Virgins' (the 'Foolish Virgins' stand opposite, on the other side of the arch), is evidence of the feverish nature of the artist's practise by this stage in his life. He saw this major commission as an opportunity to challenge the greatness of Correggio, and most critics agree that his obsessive energy got the better of him. The motif of the dove takes off from the exposed bellies of crabs. Swags of foliage sweep down and around the impressive gold rosettes. The Wise Virgins leave their lamps unlit, and glow instead with Parmigianino's trademark "inner light", which appears pure and white, whilst their counterparts fritter away their oil casting a yellow-gold light upon themselves. Flanking the foolish Virgins are Eve and Aaron, condemned figures in the Bible, whilst here with the wise women are images of Moses and Adam.

The golden color of the foolish Virgins, and the presence of Aaron, who provoked God's wrath by making a golden calf, could be an act of self-awareness from the alchemy-obsessed painter, an attempt to purge through his work a pre-occupation which, according to Vasari, so troubled his final years. Though the fresco is widely considered to be wayward and incoherent in its symbolic programme - Gould for instance notes a "striking disregard for theological consistency" while Freedberg calls its methods "laggard in the extreme" - one detail is agreed to be a triumph: the depiction of Moses wielding the tablets. Sir Joshua Reynolds himself didn't know "which to admire most, the correctness of the drawing, or the grandeur of the conception". For Gould however this was perhaps the only time Parmigianino "surpassed his model" in Correggio.

Tempera on fresco - Church of Santa Maria della Steccata, Parma, Italy

Madonna and Child with Saint Stephen, the Baptist, and a Donor (Dresden Altarpiece)

The "mystical, otherworldly, almost trancelike effect" that Gould senses in this painting has much to do with its vertilinear composition. The palm branch on the left of the frame, St Stephen's other arm holding up one of the stones with which he was killed, and the Baptist's cross together form a trinity-scaffold for the more fluid and musical elements of the picture. At certain points in his career, Parmigianino's command of gravity and weight within a painting was perhaps a little underdeveloped and lax. Here, however, the folds of the fabrics adorning the saints, the positioning and weighting of their arms and the attributes they hold, their bodily posture on the steps, are all masterfully observed and executed. St Stephen the protomartyr looks challengingly out towards us, openly brandishing the heavy stone. It is a bluntly emphatic evocation of his martyrdom, and a potent willing towards the achievement of religious divinity through earthly sacrifice.

The visionary power of the Virgin and Child, blessing into the space through a halo of clearing cloud, is hard to overstate. Because the figures are rendered with a slightly shimmering, blurred effect, the vision plays tricks with our perception, seemingly defying our earthly power of sight. We feel literally blinded by divine light. Gould called this the picture's "element of genius; the focal point - the vision itself - is actually out of focus...As a result the vision really is a vision." It is a remarkable achievement, and one that is exclusive to Parmigianino during the Renaissance. Whilst his peers and predecessors sought aesthetic perfection, the "Little One of Parma" wanted to amaze, confound, appal, and transcend. With this picture, he may have achieved his goal.

Oil on panel - Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Dresden, Germany

Biography of Parmigianino

Childhood

Girolamo Francesco Maria Mazzola was born in Parma somewhere towards the beginning of 1503. It was only retrospectively, once he had gained his substantial reputation during the middle-period of the Italian Renaissance in fact, did he become known as Parmigianino - "little one of Parma". He was born the fourth child to Donatella Abbati and the painter Filippo Mazzola. Before his second birthday, his father succumbed to the plague and died, aged 45, leaving the young Parmigianino to be raised by his mother and his two uncles, Pier and Michele Ilario, themselves artisanal painters. Indeed, painting was the family business and Filippo had been well-known in his provincial sphere. Sadly, so far as the family business was concerned, Filippo's brothers' abilities were considered somewhat modest by comparison.

From an artistic point of view, the city of Parma was not well placed during the early part of the 16th Century. The city was well known for its Romanesque architecture and design but Parma was unable to boast any painters of note during the years of the High Renaissance. Indeed, in cases where fresco-work was required, painters were brought in from elsewhere. As well as the plague, the wars between Papal, German-Imperial, and French forces unsettled northern Italy at this time too. Battle-zones moved constantly through the area, shifting and re-shifting centers of power, and displacing families like Parmigianino's. Isolated by events beyond his control, in an artless town far removed from Renaissance centres like Florence and Rome, Parmigianino was torn between becoming aware of his own audacious talent, and striving to match the seemingly insurmountable achievements of figures like Raphael and Michelangelo. It seems reasonable to surmise that Parmigianino's role in the development of the Mannerist style - pushing High-Renaissance ideals of balanced form and mathematical realism towards a less composed, more vivid style - owed something at least to his childhood ambivalence towards early-16th-century Italian culture.

Early Training

According to Giorgio Vasari, the famous chronicler of Renaissance painters' lives, the young and restless Parmigianino furtively produced sketches during his first writing lessons. His teacher and his uncles recognised that the boy had become heir to his father's talent and so trained him in drawing. Reports vary, but somewhere between the ages of 14 and 16 he produced his earliest extant painting, Baptism of Christ (c.1519). The painting showed details that would become characteristic of his mature work: a tumbling Etruscan landscape, a glowing treatment of skin lit from unnatural sources and figures of accentuated grace and elegance. The painting was crude and amateurish, and almost certainly includes contributions from one or both of his uncles, but it also bears witness to the early motions of a mind and hand that would be crucial in defining the later stages of Renaissance art and the Mannerist school beyond.

On the strength of his earliest works, and due in part to the efforts of his uncles, Parmigianino was contracted to complete the frescoes inside Parma's church of San Giovanni Evangelista, working alongside two painters who had settled in the city. One, Anselmi, had arrived in Parma from Siena a few years earlier, and would at the time have been the most talented painter the boy had ever known. It's likely that Anselmi would have been the defining influence on Parmigianino were it not for the arrival, around 1520, of the second painter: Antonio Allegri, better known as Correggio. The young boy experienced something like trauma when he saw Correggio's completed cupola at San Giovanni Evangelista. If we are to believe Parmigianino biographer and critic Cecil Gould, "an indefinable mixture of admiration, envy, and resentment of Correggio's greatness was to be perhaps the chief emotion of Parmigianino's life".

Despite learning by the master's side (as they painted the walls of the San Giovanni) Parmigianino never became formally apprenticed to Correggio. In fact, there is no evidence that he ever underwent any formal apprenticeship in the workshop of an established artist or draftsman. It appears rather that Parmigianino was largely self-taught, taking sketches after Correggio's work, from observing him paint, and by learning compositional techniques from drawings and chiaroscuro-copies of works by Michelangelo that Correggio had made while on visits to Florence and Rome. Parmigianino's abilities were raw, but he managed nevertheless to produce significant works including Bardi Altarpiece (c.1521).

Correggio's frescoes at San Giovanni earned him a flurry of commissions in the area, and so he took up residence in Parma. Parmigianino's work was however interrupted in the early 1520s when ongoing conflicts between the Empire and the Church convinced his uncles to depart for the town of Viadana. Parmigianino's time in this even more remote town appears to have been relatively productive. This may be down to the fact that he was joined in Viadana by Girolamo Bedoli, a gifted painter from his uncles' studios who was betrothed to Parmigianino's cousin.

Returning to Parma sometime during 1523-4, Parmigianino turned his thoughts towards Rome, perhaps hoping to move out from under Correggio's shadow. However, shortly before leaving Parma, he produced many important works, three of which he would take with him to Rome in the hope of announcing himself to potential patrons. One of these was the famous Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror (c.1524).

Mature Period

Aged just 21, Parmigianino arrived in Rome with his distorted self-portrait, Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror in 1524, just as the Renaissance cusped into what is now known as its "post-peak" phase. It is possible, judging by certain pictorial and compositional elements which Parmigianino began to explore, that he arrived in Rome via Florence where he briefly met Michelangelo. However, the dominant problem for all aspirational painters was how to follow the masters of the High Renaissance who seemed to have perfected compositional form; to have truly captured earthly beauty; and to have expressed religious visions so consummately. Though his painting style had become more finished, the question of how best to apply his notable talents still brought Parmigianino considerable inner turmoil.

The paintings he brought with him to the city were warmly received by the new Pope Clement VII. He gifted one of these, a Madonna, to the Pope's young nephew, Ippolito de' Medici, who became henceforward the most notable patron of Parmigianino's works. Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror, meanwhile, passed into the hands of the poet Pietro Aretino, and then on to Alessandro Vittoria, a Venetian sculptor, who duly displayed it as a popular curiosity.

On the strength of these paintings, most biographers agree (Gould, for one, accepts Vasari's account) that Parmigianino was asked by Clement to paint the Hall of the Popes at the Vatican. The commission, however, never materialised, and Parmigianino joined the ranks of talented but frustrated "post-peak" painters. Parmigianino was left to trade techniques and ideas, and to paint minor loggias and frescoes, with the likes of Rosso Fiorientini, and Michelangelo's wayward protégé, Sebastiano del Piombo (who, incidentally, shared Parmigianino's love and talent for playing the lute).

In 1527, Imperial forces of Charles V sacked Rome, raiding houses, murdering and raping civilians, and claiming the city for the Holy Roman Empire. Parmigianino, rapturously absorbed in painting his Madonna and Child with the Baptist and St Jerome (c.1527), was oblivious to the uproar. German troops stormed his residence and found him in his studio. Mythology tells it that the troops froze, stunned by the angelic beauty of the young painter's face, the innocent intensity of his concentration, and the supernatural light of the painting itself. They could not bring themselves to harm either the artist or his work, and instead kept him in their employ for some months, producing pictures and portraits. Eventually, Parmigianino would escape Rome with the help of his uncle. Their plan was to make once more for Parma, but the painter found a temporary home in Bologna instead.

After very possibly making another visit to Florence - and being introduced there to the almost surrealist experiments of the painter Jacopo da Pontormo, an important influence on his later work - Parmigianino settled in Bologna in 1527. Other than a notable St Cecilia by Raphael and Noli me Tangere, a masterpiece by Correggio (who was becoming an inescapable presence in Parmigianino's life), 1520s Bologna was home to precious little by way of great paintings. Parmigianino found that he was very much the star-turn, and his time there was perhaps his most productive and most happy. He made great strides in the art of graphics, producing etchings and chiaroscuros of a quality far beyond what had been done in the province before. He was commissioned to paint the altarpiece for the church of San Petronio, produced a startling self-portrait, and made one of his greatest paintings, The Mystic Marriage of St Catherine (undated, but certainly from the Bologna period).

Having already witnessed the sack of Rome, fate had it that Parmigianino was to be present at another great historical moment. In 1530, whilst the painter was still resident in Bologna, Charles V was crowned Holy Roman Emperor by Pope Clement VII in the city. This marked the final time that an Emperor would be crowned by a Pope. Charles is remembered as the first ruler whose domain was described as "the empire on which the sun never sets". Parmigianino was present at the banquet and based on his sighting of the new Emperor, Parmigianino painted an unorthodox and fascinating portrait. Despite its strange energy and flashing brushstrokes, it pleased Charles very much. Unfortunately for the painter, this interaction would go down in posterity as yet another missed opportunity. Reportedly, on the ill-advice of a friend, Parmigianino took the portrait back, saying it was unfinished. He never re-presented it to Charles. The payment and subsequent commissions which would surely have otherwise followed were unforthcoming.

Later Years and Death

Upon returning to Parma in 1531, Parmigianino stayed briefly in his family home with his uncle Pier. He and Pier no longer saw eye-to-eye however and his daughter and her husband, the painter Girolamo Mazzola Bedoli, were now the focus of his patronage and hospitality. Soon thereafter Parmigianino took up a solitary and separated residence for the final phase of his short life.

Though Correggio himself had moved on by this point (and there are suggestions that Parmigianino deliberately returned only after the master-painter had left), Parma was still colored by his works, his influence and his reputation: the town still abuzz with the beginnings of Correggio's great legacy. It is likely this had a profoundly negative effect on Parmigianino, and he felt himself once more shrouded in his old rival's shadow. However, Parmigianino still received a commission to paint a half-dome at Parma's Santa Maria Steccata. As Gould tells us, Parmigianino "wanted to challenge Correggio [with the commission] and then found, when he tried, that he could not".

For his fresco designs for the Santa Maria's Choir Vault, Parmigianino had to take into account the huge coffers that dominate the barrel vaults. His design (some preliminary sketches for which are held at the British Museum in London) featured vase-bearing maidens standing between the coffers with the remaining space being filled with swags, shells, crabs, flowers and birds. Parmigianino convinced the specialists who made the rosettes from his designs, to allow him to gild the flowers in gold-leaf himself. He obsessively performed the task alone, over and over again, believing he was turning the wood into gold. Vasari had made the claim that alchemical obsessions had driven Parmigianino to a kind of distraction, and in support of that argument, work on the fresco was so slow that Parmigianino was forced to sign a new contract with the church in 1535. A further three years on still, the church agreed another extension but finally ran out of patience in December 1539 when they had Parmigianino arrested. The artist was released on bail but, before he fled to Casalmaggiore (where he died in the following year), he found time, in a fit of pique, to storm the church and vandalize part of his very own fresco.

The Steccata church was consecrated and declared finished in the same year (1539). Although Parmigianino's work was incomplete, the remaining swags and crabs and lobsters and frogs of the vault were shockingly vibrant and totally original. However, his contributions were not seen as "masterful" but rather bewildering to the contemporary churchgoers who saw them. The unfinished vault still stands however as a monument to a brilliantly gifted but essentially wandering "post-peak" Renaissance mind.

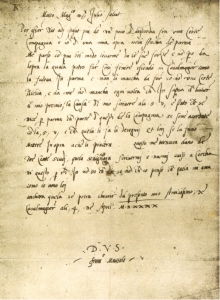

As an interesting endnote to the Steccata saga, Parmigianino, concerned that the work be completed in his absence as per his designs, wrote back to Parma on the 4th of April 1540, addressing Giulio Romano, who was tipped to lead the completion of the half-dome. It is the only surviving personal message in Parmigianino's handwriting, and shows a stubborn, unyielding mind, worried about his money and his reputation. It concludes with a strange, ambivalent statement, leaving an image of a guarded and neurotic man: "Please deign to write to me and give me advice on this matter as I know not what to say except that I think you love me as much as I love you..."

In the midst of the Steccata project, Elena Baiardi commissioned Parmigianino to paint the altarpiece for her husband's (Francesco Tagliaferri) funerary chapel. The result was arguably his most famous work, the Madonna of the Long Neck (c.1535-1540). In this piece his propensity to elongate and exaggerate the human form comes across with a poise and an expressive control that is possibly unrivalled elsewhere in his work. Whilst at Casalmaggiore, however, Parmigianino summoned the effort and self-control to gain one final commission, and through it he produced a masterpiece of near equal standing: Madonna and Child with Saint Stephen, the Baptist, and a Donor (c.1540) (otherwise known as The Dresden Altarpiece). Painted with the same care and refinement as Madonna of the Long Neck this piece still shows the eccentricities that make Parmigianino such an arresting painter. There are many who believe indeed that The Dresden Altarpiece competes with Madonna of the Long Neck as his finest work.

Parmigianino died on August 24, in the year 1540. As was his wish, he was buried naked with a cypress cross at his breast. He was 37 years old, equalling Raphael in the untimeliness of his death. Tradition has it that Parmigianino was killed by lung complications caused by the fumes from his alchemical experiments. In this case his explorations in transmutation finally did lead to a form of transcendence. He is buried at 'La Fontana', Motta San Fermo, just outside Casalmaggiore.

The Legacy of Parmigianino

In his paintings, Parmigianino's figures are often their own light-source, much as he himself was essentially self-taught, never formally apprenticed. He is a strange and singular figure whose influence stretches far. There was likely some cross-pollination with Correggio, but more importantly his elongated Madonnas and saints were the first truly Mannerist figures, and very directly influenced El Greco, Tintoretto, Benvienuto Cellini, and others from the Mannerist school. The young painter's willingness to begin deconstructing the formal perfection of his early-Renaissance predecessors was a subtle but seismic shift in the history of art, and paved the way for further innovations in the years following the High Renaissance. Parmigianino is also attributed with being amongst the very first Italian etchers. His work influenced artists such as Andrea Schiavone, who learned to etch directly from Parmigianino's prints, and Battista Franco, who would go further in their experiments with etching techniques. Though his unorthodoxy and his strange passions perhaps cost him in terms of patronage and reputation during his own lifetime, his legacy is that of an innovator, a true original whose importance endures right up to the contemporary moment.

Influences and Connections

-

![Michelangelo]() Michelangelo

Michelangelo -

![Raphael]() Raphael

Raphael -

![Jacopo Da Pontormo]() Jacopo Da Pontormo

Jacopo Da Pontormo - Correggio

- Michelangelo Anselmi

- Rosso Fiorientini

- Sebastiano del Piombo

- Ippolito de' Medici

- Pope Clement VII

- Pier Ilario

-

![El Greco]() El Greco

El Greco -

![Tintoretto]() Tintoretto

Tintoretto - Correggio

- Giulio Romano

- Girolamo Bedoli Mazzola

Useful Resources on Parmigianino

- ParmigianinoOur PickBy Cecil Gould (1994) / Definitive critical and chronological biography including analysis and reproduction of all known works, including drawings and etchings

- Parmigianino: His Works in PaintingBy Sydney J. Freedberg (1971) / Long considered the authority on the painter. Critical history of the paintings.

- ParmigianinoOur PickBy David Ekserdjian (2006) / Exhaustive catalogue of the history and influences behind all of the painter's works, including the most in-depth and thorough analysis available of Madonna of the Long Neck

- ParmigianinoOur PickVarious contributors, edited by Dominique Cordellier (2015) / Latest collection of critical essays on Parmigianino

- Self Portrait in a Convex MirrorOur PickBy John Ashbery (1974) / Pulitzer and National Book Award winning collection of poems by the great American poet, John Ashbery, inspired by Parmigianino's famous self-portrait, including the title-poem which responds directly to the painting

- The Story of ArtBy E. H. Gombrich (London Phaidon Press, 1995)