Summary of Camille Claudel

Talented from youth, inspired by nature, and captivated by love, Camille Claudel unlocked the emotive power of sculpture after centuries of its subtleties having been obliterated by excessive polishing and focus on technique. Drawn intuitively to the innocence of children, the experience of old age, and the complexities of love and madness, Claudel exhibited great skill in the portrayal of raw and real emotions. Whilst sculpture until this point had typically dealt in hard and impenetrable subject matter akin to its materials, Claudel managed to peer beyond the surface and add transformative elusiveness to formulaic solidity.

Sadly, following the end of her long-standing affair with fellow sculptor, Auguste Rodin, Claudel's own underlying delicacy unravelled and she experienced a psychological breakdown. As unsupported personally as she had been professionally, her own family placed her in an asylum. This action was the equivalent of caging a bird, and as Claudel could not fly in captivity, she instead became the living embodiment of her pain, a symbol of the destruction of love, existing only in her own despair. Although the woman herself died in relative obscurity, interest in her art grew organically and there is now a National Museum in France dedicated to Claudel's life's work.

Accomplishments

- Every work by Claudel is infused with an intensity of expression, psychological investment, and sense of truth that is arguably lacking in the work of her male contemporaries. The likes of Alfred Boucher and Auguste Rodin had tendencies to overlay emotional reality and lived experience with projections of fantasy and a finishing sheen of beauty, and as such they neglected to explore 'meaning', or to move away from outdated neo-classical and imperial styles. It was Claudel who was keen to experiment - influenced by Art Nouveau and Japanese prints - her sculpture became 'expressionist'.

- Claudel's sculptures reveal an interest in relationships, and in particular the dynamism created by the gathering of small groups (including couples). Whilst the portrait busts that she made typically exude a sense of calm, her groupings emit abundant energy. Like others at this time (most notably Sigmund Freud) Claudel attempted to understand moods and behaviours that were triggered by human interaction. Like Edvard Munch, she worked repeatedly on the same subjects illustrating a tendency towards obsession.

- Claudel experienced ongoing torment in both her personal and professional life - due to being at best sidelined and at worst completely betrayed - and this writhing agitation was often made visible in her work. Professionally, her career was a constant struggle, from being one of the first women to formally study when such was still frowned upon, to later finding it difficult to gain financial support to help cast vulnerable plaster models into lasting bronze. Personally, she felt betrayed by Rodin who aided her emotional damage to such a degree that once institutionalized, she would no longer make art in fear that he would steal her ideas.

Important Art by Camille Claudel

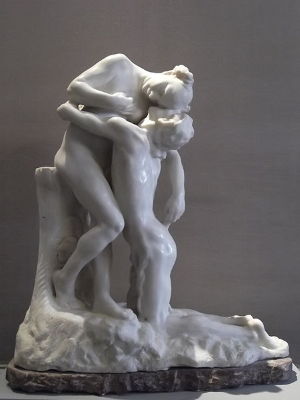

Sakuntula (or Vertumnus and Pomona)

Although also smooth-lined and romantic, this sculpture differs radically to those of her male contemporaries. Similar in composition to Rodin's Eternal Idol (1889), whilst in his sculpture we are confronted by highly polished sex and desire, here Claudel depicts love as a power of the mind, as well as an attraction between bodies. The lovers are connected as equals as they gracefully unite their heads. The title and subject of the piece originally comes from the legendary Indian tale by the poet Kalidasa, in which Sakuntula is reunited with her husband following a long magic spell. First modelled in 1886, Claudel repeatedly fought for a state commission for a marble version but was constantly refused. It was only in 1905, when the Countess of Maigret was still Claudel's financial sponsor that a version was finally carved in marble. At this point the sculpture was renamed Vertumnus and Pomona after the Roman God of metamorphosis who initially disguised himself as an old woman to gain the trust of the goddess of fruit. Indeed the sculpture is also sometimes known as The Abandon, and with these three different titles, moves from Hindu to Greek mythology, to personal experience.

Originally read as a surrender to love, the renaming in 1905 to introduce an aspect of disguise points towards Claudel's distrust of Rodin after their separation and complicates the meaning. According to the art historian, Angelo Caranfa, the piece expresses Claudel's worry that she can never detach herself entirely from Rodin. A letter written to Gustave Geffroy in 1905 indicates that the work had a particular personal and artistic significance for Claudel, "(...) I am still coughing and sneezing as I polish with rage the group destroying my tranqulity: with tear-filled eyes and convulsive groans I finish the hair of Vertumnus and Pomona. Let's hope that despite different accidents, they shall be finished in a logical way, suiting two perfect lovers." The sculpture is Claudel's hopeful recounting of tender, real, and vulnerable love. It is not an idealised symbol of love as Rodin's The Kiss has come to represent, but instead reveals love, even if in time lost, that was actually experienced by two people, not an untouchable vision, but a momentary actual joy felt in the course of everyday life.

White marble

The Waltz

Immortalised in bronze, a beautiful couple dance together in passionate, sensual, and harmonious embrace. They are each attentive to the other's body and spirit in the space; they are in love. As the duo lean significantly to one side the notion of the precarious in relationships is introduced, and the idea that what is quickly built can also easily fall comes to mind. The overall energy, however, is intensely joyous and romantic.

Most notable and unusual for the composition is the fact that whilst the male figure remains whole, his body fully formed from head to toe, the woman at the point of her buttocks becomes swirling cloth. Read in a positive light, the woman's transformation shows affinity with the environment and a great sensitivity to all that surrounds her. Construed negatively however, we see a warning sign that the female sense of self can be upset and in extreme cases, begin to disappear when engaged in all-consuming romance. Interestingly, after his ten-year affair with Claudel, Rodin began another ten-year affair with the British painter, Gwen John. Equally damaged by the relationship, John's self-portraits became increasingly muted and less defined afterwards.

Claudel made The Waltz in the same year that her relationship with Rodin began. In style and in spirit, the work introduced her as a significant artist in her own right, showing a love for the creation of movement in solid form and also her interest in the underlying psychology of relationships. When first exhibited however, the piece was confronted by gendered censorship and ignited indignation from critics; Armand Davot wrote, "this work cannot be accepted (...) the violent reality which emanates from it would forbid it, despite its value, a place in a public gallery." Mainly to ensure funding to get her clay maquette cast in bronze, Claudel modified the sculpture - which originally did present a whole nude woman -before presenting it to the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts. Without realising, by forcibly adding 'a skirt', the critics had in fact added a new dimension to the meaning of this sculpture. Once altered, not only did it prefigure Claudel's own sad disintegration of self, but it also revealed the artist's interest in Art Nouveau, characterised by flowing, non-linear shapes inspired by nature. It is rumoured (although not confirmed) that Claudel may also have had a short relationship with the composer, Claude Debussy, at this time. She gave Debussy the sculpture, which remained in his study until his death.

Bronze

Clotho

The year following the official end of her romantic relationship with Rodin, Claudel cast Clotho in plaster. The old, naked woman stands as a vision of writhing horror and despair. All skin and bones, with hanging breasts, and a confused toothless grimace, the woman grows from the rock beneath her and she is being consumed by her own hair. Her unruly locks are also serpent-like as they wrap around her weakened form, perhaps making reference to the snake that lured Eve to her demise. Clotho though is the name of the youngest of the three fates in Greek mythology. Together with her three sisters, Clotho spun the 'thread' of human fate, whilst Lachesis dispensed it and Atropos cut it. Suddenly, the hair of Clotho becomes the thread of life and despite Claudel's sorrow at the loss of her love, she recognises that such is not misfortune as much as the weight of her destiny. It seems too that she is also aware that such a burden will follow her into old age.

Throughout their ten-year relationship, both Claudel and Rodin were interested in the representation of old age. It became somewhat of an obsession in the work of Rodin, who had already explored the theme in She who was the helmet-maker's once beautiful wife (1884). It may be that Claudel had an anxiety surrounding old age, for as their relationship deteriorated she was aware that Rodin was attracted to younger lovers.

The work also shows how as an artist, she is able to portray unapologetic, raw representation of the female nude in a way which was considered scandalous and unacceptable at the time. The plaster model of Clotho shown at the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in 1893 was received with mixed results. While Claudel herself never recovered from the tone of distress that she introduces in this work. Indeed, art historian Griselda Pollock notes, "Alone as a woman of her class, not married to the man with whom she had a sexual relation, perhaps deeply distraught by the loss of love and undergoing major changes in her life cycle, while she watched her own sculptural ideas make Rodin the lionised figure of French sculptures, she may well have had some kind of psychological breakdown."

Plaster

The Gossips

A group of four women form a circle, heads close together with expressive gestures indicating an animated 'secret' conversation. Huddled behind an encroaching screen, three of the women listen to the other woman as though they are conspiring. The work speaks loudly of Claudel's increasingly unstable mental health and growing paranoia. Are the women plotting against the artist, or is it the artist herself who is presenting advice to a small audience? Claudel writes to her brother that she was inspired to create The Gossips having witnessed a group of chattering women in a train carriage. The grouping of these women does seem to emphasise feelings of Claudel's own psychosis and the notion that others want to harm her. The walls appear heavy, as though they could move in and crush life at any moment, perhaps making reference to the experience of pressure within Claudel's mind.

Claudel had been separated from Rodin for several years by this point and increasingly attempted to absorb her own personal struggles into her work. Between 1893 and 1905 she called her pieces 'sketches from nature', drawing from life around her, these were original, captured great depth of expression, and were in general well-received. Claudel created many copies of The Gossips all the while experimenting with different materials. Art critic Gustave Geoffroy called the work "an apparition of truth, intimacy (...) a marvel of comprehension and human sentiment." At this time there was a great obsession in Vienna surrounding mind exploration and making portraits of those most expressive in society, including the mentally ill, but in France it was still extremely rare for artists to derive inspiration from mundane, everyday scenarios rather than from allegory or myth. In this sense, both Claudel and her works were pioneers of a new wave focused on self-investigation that would dominate 20th-century art.

Onyx Marble and Bronze

Maturity

Down on her knees, a young woman begs her lover not to leave. Although he reaches with an out stretched hand, he does not look back as he is enveloped into the arms of an older woman, and guided away. Although possible to read the work as a general allegory of the passage of time from youth to old age, because of known facts about the relationship between Claudel and Rodin it is more likely that the sculpture has meaning rooted in biography. By this time, Claudel had been involved for ten years with Rodin, as his assistant, his pupil, and his lover since the age of nineteen. The couple had recently separated because Rodin refused to leave Rose Beuret. Despite romantic estrangement, Rodin continued to try and find Claudel work and Maturity was the result of these efforts. In 1899 the work was presented to the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts to consider whether it should be cast in bronze. Somewhat strangely, as Rodin was on the board, the cast was not commissioned at this time, nor was the work admitted to the 1900 Universal Exhibition. The work was finally cast in 1902 with the financial support of Captain Tissier.

Rodin's involvement surrounding the work therefore becomes ambiguous; Claudel began to believe that he had intentionally sabotaged the work's development. In the words of Claudel's brother, the poet, Paul Claudel, this was an entirely autobiographical work, "(...) this vulnerable soul, this young girl on her knees...that's my sister! My sister Camille. Begging, humiliated, on her knees and naked, that proud and haughty creature (...) and what's being taken away from her at that very moment, under your very eyes, is her soul!" However, once again - as in Clotho - despite her pain, Claudel recognises that what is happening to her is less misfortune than it is destiny. Destiny has been recorded as an alternative title for the work and the old figure once again recalls Clotho, or this time Lachesis who determines the length of the life thread once woven by her sister. It seems that it has been decided by fate that Claudel will be abandoned and humiliated in love and left alone and exposed without any support or encouragement at the height of her career.

Bronze

The Wave

The Wave is a joyful image of three women 'set free'. They frolic naked emerged in the grandeur of nature. Their hair is abundant and unruly just like the sea itself and control is ousted as the immediacy of experience is fully embraced. Sadly and ominously however, it is clear that this playful time dancing in the sea cannot last and the wave will soon crash down. Indeed, the three women may be the three fates themselves (a repeated motif for Claudel), acting as metaphor for the sorrowful course that the artist's life must take and cannot be prevented. The three women together could also serve to make a nostalgic gesture back to earlier times when Claudel shared her studio with fellow female sculptors, to a time when the future looked bright and fate had not yet played her cruel hand.

Shown first in its plaster version in the year that it was made, the artist later chose to cast the bathers in bronze and replicate exquisite ocean tones by using onyx marble for the wave. At the time in Paris there was a literal 'wave' of enthusiasm for Japanese woodblock printing and especially for the work of Katsushika Hokusai. Claudel would have seen The Great Wave (1832), getting a direct inspiration for her own work.

Indeed Japanese art also became a great influence for Vincent Van Gogh; he shared Claudel's experience of mental instability and had the same desire to explore such torment through his art. Although successful in incorporating a complex array of new influences and showcasing great skill, this work bears testament that Claudel will not fight the might of nature any longer, that this large looming wave will bear down, and that she will be tragically consumed and lost.

Onyx Marble and Bronze

Biography of Camille Claudel

Childhood

Camille Claudel was born in 1864 in Fère-en-Tardenois, Aisne, France. Her father made a living from mortgage dealings and bank transactions, and her mother came from a long line of wealthy Catholic farmers. The family moved from place to place, one of which was Villeneuve-sur-Fère, which made a deep impression on Claudel and the family would continue to spend summers there even after moving on. In 1927, Claudel wrote of Villeneuve to her younger brother, the poet Paul Claudel, "What joy if I could find myself at Villeneuve again! This beautiful Villeneuve unlike anything on earth!". It seems that the children enjoyed the landscape and atmosphere of this countryside home in particular, and may have contributed to Claudel's particular love of nature, and literally for the earth. When the family moved to live for three years at Nogent-sur-Seine - at which time Claudel was 12 - she was already working with clay. Her early work attracted the attention of the already successful sculptor Alfred Boucher, who advised her father to encourage his daughter's artistic career. In response to such advice, in 1882, along with her mother, Paul and her younger sister, Louise, Camille Claudel moved to the Montparnasse neighbourhood of Paris while her father continued to work elsewhere and supported the family from afar.

Early Training

At the time, very few spaces were open for women to study art. The official École des Beaux-Arts remained exclusively for men until 1897. Thus, Claudel studied sculpture at the more forward thinking, Académie Colarossi, where promising female artists were not only admitted, but where they were also (highly controversially) permitted to draw from the male nude. With her confidence bolstered, in 1882 Claudel rented her own studio space, which she shared with three British sculptors Jessie Lipscomb, Amy Page, and Emily Fawcett.

Following her earlier encounter with Alfred Boucher, once in Paris, he became Claudel's mentor and they established a strong and productive student-teacher relationship. Claudel sculpted his bust, and he depicted her in the very tender piece, Camille Claudel lisant (1882). Boucher's sculpture powerfully reveals that Claudel was not a typical woman for her era. Not only did she ambitiously carve and model her own highly original works of art, she also and perhaps more significantly, made those around her 'see' differently. While Boucher would usually present the classic female body, languid, on offer, and seductively emerging from stone, his depiction of Claudel stands out as a radical exception. Claudel sits clothed, with a book in hand, and with her eyes closed, not in erotic reverie this time but instead committed to deep thought and self-development.

Having won the Grand Prix du Salon, unfortunately for Claudel, Boucher soon left Paris for Italy. Upon his departure, he asked Auguste Rodin to become the tutor for his group of women pupils. At the time, Rodin was forty-three years old with a strong reputation as a sculptor. Claudel quickly became not only one of his pupils, but also his muse and lover, starting to work in his workshop in 1883. Whilst her father continued to support her talent and life choices, the rest of her family condemned her henceforth and forced her to leave the family home. In 1884, Claudel became one of Rodin's official studio assistants and worked, somewhat ironically, on both The Kiss (1882) and on The Gates of Hell (1880-1890) with her lover (the two also happen to be some of Rodin's greatest masterpieces). Rodin was always open about his belief in Claudel's talent, originality, and creative genius. He talked of her as his best assistant but refused to end his relationship with Rose Beuret to be with her exclusively in romance. Ensnared by Rodin's 'double life', Claudel carried a rage and jealousy surrounding the situation that would later grow into paranoia.

Mature Period

Alongside becoming Rodin's muse and the source for many of his portraits and allegories, her own work was getting stronger and she became a great influence on Rodin stylistically. Her 1886 sculpture, Shakuntala, won a Salon Prize. Her daring use of the nude combined with strong psychological message had started to attract attention from art critics.

Meanwhile however, her relationship with Rodin was falling apart as he refused to separate from Beuret and marry her. By 1892, after an almost 10 year affair, the couple officially parted and the separation inalterably shifted the tone of Claudel's art, always inseparable from her life. Works that followed, for example Clotho (1893) and Maturity (1895), display sorrow emotionally, but also in practical terms, they are no longer supported by the team and finances that she previously had access to through Rodin's studio. Rodin did attempt to continue to help to further Claudel's career beyond their time as lovers, but Claudel felt such strong resentment and mistrust towards Rodin by this time that she refused any help. She labelled Rodin as a career saboteur and referred to him as "The Ferret" in letters, who alongside the "bande à Rodin" had caused her great harm. Despite growing unhappiness, Claudel experienced a period of productive creativity. Inspired by everyday reality, Art Nouveau decorative curves, and memorable images from Ukiyo-e Japanese prints she made some of her most original works. Her experiments with different materials and combination of marble and bronze were unprecedented and attracted the financial support of the Comtesse de Maigret in 1897.

Late Period

Claudel had been working and living alone in her studio on the île St-Louis since 1899 and despite support from the Comtesse de Maigret, continued to have financial difficulties. It is recorded that Rodin paid her rent in 1904 and continued to search for commissions for her. From 1905 onwards, Claudel's mental health appeared to be deteriorating, as she sporadically experienced bouts of rage and destroyed her own work. Following an argument with the Comtesse she also lost her rich patron at this time. Despite increasing paranoia and isolation, Claudel did have other supporters; the art critic Gustave Geoffroy was a strong advocate of her work, as was the writer and critic Octave Mirbeau who wrote about her talent in the press. It seems though, that this was not enough as Claudel was convinced that the entire world was set against her and seemed to produce less original work but instead further copies of pieces that she had already made.

Her behaviour became increasingly unsettling to others as she secluded herself in her studio, installed traps behind her doors and only spoke to visitors through her shutters. She destroyed most of the work in her studio in 1912, and then tragically in 1913, her ever supportive father died. Claudel was not informed of her father's death and instead, now without opposition, her mother, her brother, and her sister instantly took the opportunity to have Claudel diagnosed with paranoia and committed to an asylum.

Following this sad extraction, the remains of Claudel's workshop were destroyed. Doctors tried to reason with Claudel's family that she was by no means insane, but the family wanted Claudel out of their lives and effectively imprisoned. In 1917, Claudel wrote to her former doctor, trying to negotiate her release, "I am reproached (what a terrible crime!) to have lived alone, spending my life with cats, to have felt persecuted! It is based on accusations that I have been imprisoned for five years and a half like a criminal, deprived of freedom, deprived of food, fire and the most basic essentials." Out of utter despair and embroiled in a nightmare, Claudel abandoned sculpture completely. Loyal admirers of her work openly criticized her family, while Rodin attempted to intercede in his former lover's favor without success. Claudel spent thirty years at the asylum of Montdevergues during which time she received only a handful of visits. When her old friend, Jessie Lipscomb visited her in 1929 she photographed Claudel who appears as the interesting shell of a once magnificent creature.

She died alone in 1943 at the age of 78, and was buried in the mass grave of the institution with her body never claimed by her family.

The Legacy of Camille Claudel

Following a long period of relative obscurity, with her work having been significantly overshadowed by her relationship with Rodin, it has now re-emerged and become rightfully recognized for its ingenuity in the portrayal of emotion and human nature. More so than that of any of her male contemporaries, the work of Claudel looks forward to the expressionist career of Edvard Munch and the Post-Impressionist journey of Vincent van Gogh. Diverging from the typical illusionist and historical depictions of the time, Claudel's approach prefigures the early-20th-century focus on autobiography, exploration of relationships, and self-representation, both in art and in the introduction of psychoanalysis. Although mildly influenced technically by Alfred Boucher and Auguste Rodin, Claudel was principally an innovator driven by her own individual experience.

Claudel's struggles with mental illness, her stigmatisation as an unusual solitary character, and decision to live on the borders of society raise questions surrounding the artistic temperament and what it in fact means to be an artist. Furthermore, her struggles cannot be dissociated from her sex as woman, for the eccentric and/or antisocial behaviour of male artists had already long since been tolerated. As a light at the end of a mostly long dark tunnel, the inauguration of the Musée Camille Claudel on the 26th of March 2017, the international day for women's rights, has acknowledged her influence to stem even beyond art history, to become a symbol for women's struggle to raise themselves up from the falling debris of a long standing patriarchal system.

Influences and Connections

-

![Michelangelo]() Michelangelo

Michelangelo -

![Donatello]() Donatello

Donatello - Benvenuto Cellini

-

![Auguste Rodin]() Auguste Rodin

Auguste Rodin ![Alfred Boucher]() Alfred Boucher

Alfred Boucher- Claude Debussy

-

![Art Nouveau]() Art Nouveau

Art Nouveau -

![Romanticism]() Romanticism

Romanticism ![Greek sculpture]() Greek sculpture

Greek sculpture- Japanese art

- Antoine Bourdelle

- Gaston Schnegg

- François Pompon

- Ernest Nivet

-

![Auguste Rodin]() Auguste Rodin

Auguste Rodin ![Octave Mirbeau]() Octave Mirbeau

Octave Mirbeau- Jessie Lipscomb

- Paul Claudel

-

![Expressionism]() Expressionism

Expressionism -

![Post-Impressionism]() Post-Impressionism

Post-Impressionism ![Feminist Movement]() Feminist Movement

Feminist Movement

Useful Resources on Camille Claudel

- Camille Claudel: A Sculpture of Interior Solitude (1991)Our PickBy Angelo Caranfa / Detailed account of the artist's life and work

- Camille: The Life of Camille Claudel, Rodin's Muse and Mistress (1988)Our PickBy Reine-Marie Paris

- Mind of Steel and Clay: Camille Claudel (2014)Our PickBy Enrique Laso / Details about the artist's time in an asylum, from the view of her nurse

- Camille Claudel: A Life (2002)By Odile Ayral-CLause / Biography of the artist

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI