Summary of Marie Bracquemond

Despite being referred to as one of "les trois grandes dames" (the three great ladies) of the Impressionist movement by the famous French art historian, Henri Focillon in 1928, the work of Marie Bracquemond was somewhat obscure until at least the 1980s. A good deal of what we know about her comes from a brief biography that Pierre, her only child, wrote about his artist parents, Felix and Marie. In contrast, it was her husband, the evidently domineering Felix who resented her career and loathed the Impressionist style, who played a significant role in downplaying the importance of Marie Bracquemond in the larger context of the Impressionist movement.

Nevertheless, she persisted in developing her apparently prodigious talent, incorporating en plein air painting techniques of her youth into her professional regimen while working with some of the most notable artists of the period such as Claude Monet and Edgar Degas and, later on, Paul Gauguin. Gradually, Bracquemond established her own distinctive, colorful approach to the style and she was rewarded with invitations to exhibit her work, including at the Impressionist exhibitions in 1879, 1880, and 1886.

Accomplishments

- Bracquemond began her career as an academic painter whose polished, Realist style had far more in common with the anachronistic work of Salon-approved artists like Cabanel, Regnault, and Gérôme than emerging avant-garde painters like Monet and Degas. However, after having met the latter two, her style began to change dramatically as she absorbed the precepts of Impressionism and by the 1880s her painting could only be described as fully Impressionist.

- Bracquemond is known for having been something of a recluse, particularly as she aged. While earlier in her career, she enjoyed going out and painting en plein air like most of her Impressionist colleagues, by mid-career, many of her paintings were made in the garden of her home in the southwestern Parisian suburb of Sèvres.

- Her work after 1886 began to change with her palette becoming increasingly more vibrant. This transformation was due in large part to Bracquemond having met Gauguin in 1886. The two were introduced by Felix, who had befriended the then-impoverished, budding new artist. At Gauguin's encouragement, Bracquemond enhanced her relatively subdued Impressionist palette so that it became much brighter, all of which was ironic given that her husband took exception most of all to her use of color, preferring printmaking in black in white to his wife's chosen medium of oil painting.

Important Art by Marie Bracquemond

Woman in the Garden

Bracquemond's Woman in the Garden reveals her roots in academic painting. In 1859, she was accepted as a pupil to the legendary painter, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. Despite learning a great deal from the French master, she reflected later that she had feared his stern nature and observed that Ingres treated his female students differently in some ways than his male students. She wrote: "The severity of Monsieur Ingres frightened me...because he doubted the courage and perseverance of a woman in the field of painting... He would assign to them only the painting of flowers, of fruits, of still lifes, portraits and genre scenes." That aside, the important art critic, Philippe Burty, referred to Bracquemond as "one of the most intelligent pupils in Ingres's studio."

Bracquemond's early portraits are examples of academic Realism. Here, a female sitter, the artist's sister, Louise, who modeled frequently for her, is perched on a garden chair. The ruffled train of her white gown spills into the space between the prim young woman and the viewer. Her delicate hands, which rest on the back of the chair, are perhaps those most emphatic references to Bracquemond's teacher, Ingres. The tips of her graceful fingers are refined nearly to points, as was the practice of Ingres, famous for his usually fairly subtle, elegant distortions of the human figure.

Louise is framed by the deep green of the lush garden setting behind her. In this painting, probably produced at least half a decade after Bracquemond left Ingres's studio, the artist is still using the somewhat refined brushwork of her early, pre-Impressionist career. Another painting, The Woman in White, closely resembles this painting both in style and subject matter. In fact, the "Lady in White" or "Woman in White" became a popular theme for the Impressionist painters.

Throughout her career, Bracquemond continued to produce works of art, from drawings and prints to finished paintings, within a somewhat restricted range of subject matter: domestic scenes, portraits, landscapes, and still lifes. These were standard themes for the women Impressionists, whom, because of their gender and class - all of them middle- or upper-class women - were restricted in terms of what and where they could paint. For instance, it would not have been appropriate for a woman artist in the 19th century to paint a nude, whether male or female. "Proper" women could not move about the modern city unaccompanied, so the women Impressionists were unable to produce the kind of genre scenes that became common fare with many of their male colleagues such as lively scenes at bars and dances.

Oil on canvas - Private Collection

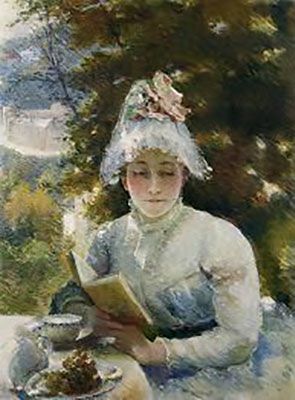

Afternoon Tea (The Snack)

By the 1880s, Bracquemond had met Monet and Degas and had begun to incorporate the loose brushwork and wistful, muted, light-infused palette of Impressionism - much to the dismay of her printmaker husband, Félix, who was famously contemptuous of the Impressionist style.

Here, Bracquemond has once again represented her sister, Louise. Attired in white once more, the young woman no longer looks directly at the viewer but is instead absorbed in reading a book. Seated at a table on the garden terrace of the artist's home, Villa Brancas in Sèvres, Louise reads while taking a cup of tea and a plate of grapes.

While the theme is typical, the style marks a dramatic departure from Bracquemond's academic treatment of such a scene. Less a portrait than a genre image, the feathery brushwork and sunlight-dappled surface of the picture, situates Afternoon Tea soundly in the Impressionist style for which she is best known. This painting is, incidentally, one of the rare ones that is in a public collection.

Oil on canvas - Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-arts de la Ville de Paris

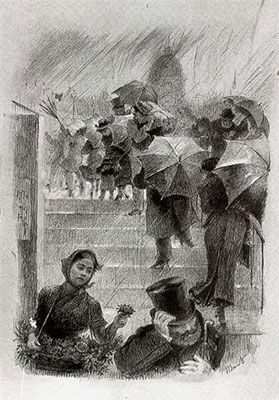

The Umbrellas

Just as her husband, Félix, had drawn Bracquemond into the decorative arts via his role as art director at the Haviland porcelain shop, so he apparently strongly encouraged her to apply her talent as an accomplished draftsperson to printmaking. In particular, etching was his favored form of printmaking and, under his instruction, she excelled. According to her son, Pierre, however, Bracquemond found printmaking far too restrained both because of its typically small format and also because she preferred working with color.

The Umbrellas is one of Bracquemond's most successful etchings, clearly demonstrating her skill at drawing as well as at conceiving of successful compositions that exploited the range of gray tones that etching could produce. Here a young woman attempts to sell flowers to a well-to-do, top-hatted gentlemen who apparently scurries past her in an attempt to escape the rain and wind, which is described by the light diagonal lines sweeping across the image. He holds onto his hat and the viewer is left to wonder why he hasn't raised his umbrella like the other pedestrians in the image.

Bracquemond, like many of her Impressionist colleagues, cropped her images so that they resembled photographs, lending them a spur-of-the-moment sense of immediacy. Because of the cropping of the man in the foreground, there is an added urgency: the viewer feels crowded, compelled to step aside and allow him to pass.

The lively composition pulls the viewer in, past the fleeing man to the cluster of umbrellas, up the stairs, and into the excitement of the modern city.

Etching - Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Three Women with Umbrellas (The Three Graces)

Also in a public collection, Three Women with Umbrellas alludes to the artist's roots in academic classicism. Its alternate title, The Three Graces, suggests that, despite her transition to the radical new Impressionist style, Bracquemond was conscious of the longstanding tradition of drawing from themes rooted in classical mythology. Bracquemond's Three Graces are thoroughly modern, fashionable Parisian women whose umbrellas protect their pale skin from the bright afternoon sun, which has virtually bleached the fabric of their dresses nearly to white.

With short, varied brushstrokes, she dissolves forms until they are comprised largely of color and light. The three women stand at the front of the picture plane, the lower portions of their dresses cropped. This unusual cropping was a major feature of the work of many of the Impressionists and, specifically Bracquemond's mentor, Degas. It owes much to the mechanical cropping of photography and the reference suggests a kind of spontaneity particular to a photo.

Oil on canvas - Musée d'Orsay, Paris

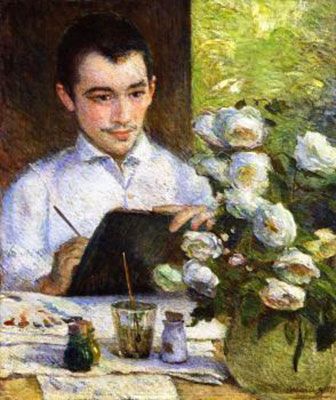

Pierre Painting a Bouquet

In this luminous portrait of Bracquemond's only child, her son Pierre seems to have inherited if not his mother's talent some of her zeal for making art. Painting an evidently small-scale still life of cut flowers in a vase, Pierre sits absorbed in his activity at a table in the bright sunshine, seemingly on a terrace - probably at the Bracquemond's home in Sèvres.

Because of the radical cropping of the work, the viewer seems to occupy the opposite side of the table from Pierre, making the portrait a somewhat intimate glimpse into the private world of the artist and her son, who seem to have likewise formed a bond over their mutual interest in making art. Bracquemond's lively brushstrokes change direction to more fully describe the effects of light on objects and the space between them. Her palette with this painting and others in the late 1880s is increasingly brighter and more expressive.

According to her son, Pierre, the resistance of Félix to his wife's chosen medium and style was one of the most formidable obstacles of Bracquemond's artistic career. Apparently, while he was quick to criticize her work, Félix refused to consider constructive criticism from his wife. When visitors came to their home, he was resistant to showing them her work. Ultimately, by the 1890s, Bracquemond almost completely relinquished painting as her husband had made it so difficult for her to pursue her career. Yet, she remained an ardent defender of the Impressionist style, once stating, "Impressionism has produced...not only a new, but a very useful way of looking at things. It is as though all at once a window opens and the sun and air enter your house in torrents."

Oil on canvas - Private Collection