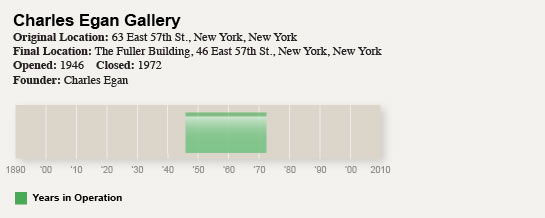

Summary of The Charles Egan Gallery

The Charles Egan Gallery was a relatively small institution on Manhattan's 57th Street, the center of all gallery activity in the 1950s. Its proprietor, Charles Egan, did not grow up wealthy nor did he possess any serious credentials in the art world, but he was very well liked by many artists of the New York School. The Egan Gallery was a small but very bright star in the 1940s and 50s, and was best known for its solo exhibitions of some of Abstract Expressionism's biggest figures, including de Kooning, Kline and Guston.

Despite having no formal training in the arts, academic or otherwise, Egan became very popular among a slew of New York artists. Egan frequented the Waldorf cafeteria and befriended artists such as Isamu Noguchi, Franz Kline, Willem and Elaine de Kooning, and Milton Resnick. Sensing that Egan was displeased with answering to others, they all encouraged Egan to open his own gallery.

Many of Egan's artist friends from the Waldorf cafeteria were surprised that they themselves were not selected for the gallery's opening show. According to Resnick, "No one took it [the exhibition] seriously." But Egan defended his position by saying, "You know, you guys, I'd never be able to sell your paintings. I'm broke, and I need to sell."

Many of Egan's artist friends from the Waldorf cafeteria were surprised that they themselves were not selected for the gallery's opening show. According to Resnick, "No one took it [the exhibition] seriously." But Egan defended his position by saying, "You know, you guys, I'd never be able to sell your paintings. I'm broke, and I need to sell."

In only its second year, the Egan Gallery managed to acquire on loan a number of paintings and exhibited an impressive group show that included works by de Kooning, Rothko, Joseph Stella, Joseph Albers, Paul Klee and Georges Braque.

- Milton Resnick remembering Charles Egan's decision to open his own gallery

"It was a tiny little hole in the wall. He had no storage space, just a closet. He had a little extra square room. That was about all. And the artists fixed it up and painted it."

- Milton Resnick

"Charlie used to go down to Bill's studio early in the morning. Bill had a way of not letting people in when he was working. They'd take walks and talk. Charlie loved to talk about art."

- Betsy Egan Duhrssen, Egan's first wife, discussing his frequent visits to Willem de Kooning's studio

Background of Charles Egan

Born in Philadelphia in 1914, Charles Egan dabbled with drawing and painting at an early age, but never expressed much desire to become an artist. He never completed high school, and in 1935 he moved to New York and took a job selling art at Wanamaker's department store. He subsequently found work as a salesman at the Ferargil Gallery and then at J.B. Neumann's New Art Circle, which specialized in older European Modern art. Despite having no formal training in the arts, academic or otherwise, Egan became very popular among a slew of New York artists. Egan frequented the Waldorf cafeteria and befriended artists such as Isamu Noguchi, Franz Kline, Willem and Elaine de Kooning, and Milton Resnick. Sensing that Egan was displeased with answering to others, they all encouraged Egan to open his own gallery.

The Charles Egan Gallery Opens

In February of 1946, Egan's gallery started out as a tiny room on the top floor of a four-story residential building on 57th Street. The gallery's very first show was an exhibition of gouaches by the Swiss artist, Otto Botto.  Many of Egan's artist friends from the Waldorf cafeteria were surprised that they themselves were not selected for the gallery's opening show. According to Resnick, "No one took it [the exhibition] seriously." But Egan defended his position by saying, "You know, you guys, I'd never be able to sell your paintings. I'm broke, and I need to sell."

Many of Egan's artist friends from the Waldorf cafeteria were surprised that they themselves were not selected for the gallery's opening show. According to Resnick, "No one took it [the exhibition] seriously." But Egan defended his position by saying, "You know, you guys, I'd never be able to sell your paintings. I'm broke, and I need to sell." In only its second year, the Egan Gallery managed to acquire on loan a number of paintings and exhibited an impressive group show that included works by de Kooning, Rothko, Joseph Stella, Joseph Albers, Paul Klee and Georges Braque.

Willem de Kooning Joins the Gallery

Egan was an enormous fan of de Kooning's paintings, and in the spring of 1948, he gave the artist his first ever solo exhibition. De Kooning was approaching 44 years of age, and after 22 years of working and struggling in New York City, one of Abstract Expressionism's true giants finally got his first exclusive, large scale show. The show was important for de Kooning and was lauded by fellow artists even though it received a tepid response from the press. Starting in 1948, Egan was de Kooning's exclusive art dealer. By 1953, however, de Kooning was lured away by the dealer and gallery owner Sidney Janis, whose gallery offered far greater public exposure than Egan's. Egan Marries and has an Affair

In September of 1948, not long after de Kooning's first show at the gallery, Egan met his wife-to-be, Betsy Duhrssen while vacationing on Martha's Vineyard. The two returned from their honeymoon around the same time Willem and Elaine de Kooning returned from a summer teaching at Black Mountain College. Elaine was stunned to discover Charles had married, as the two had been carrying out an affair for some time. The affair continued even after Charles' marriage to Betsy, and appears not to have been terribly secretive. Betsy knew about and tolerated the affair, while both Elaine and Willem had been carrying out their own extramarital affairs for years. Rauschenberg's "Combines" are Unveiled

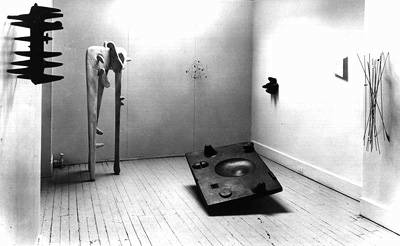

Although the artist Robert Rauschenberg would eventually be represented by the dealer Leo Castelli and achieve his early fame through the Castelli Gallery, it was at the Egan where the artist first unveiled his famed "Combine" paintings. In a 1955 solo exhibition, Charles Egan showed Bed (1955), one of Rauschenberg's first and certainly most famous Combines. Legacy of the Charles Egan Gallery

The single greatest achievement of the Charles Egan Gallery was launching the career of Willem de Kooning. While Jackson Pollock was the most celebrated American artist of the New York School by the late 1940s, a small 4th-floor art gallery in midtown gave de Kooning (revered by fellow artists but relatively unknown outside New York) his own show. Though de Kooning was not well received at the time, Charles Egan would continue to represent the artist who in a short time became Abstract Expressionist royalty. The gallery also exhibited regular solo shows for artists like Kline, Noguchi and Guston, but the Egan Gallery will always be remembered as the place where de Kooning got his first real chance at publicity. Most Important Exhibitions:

Willem de Kooning

Opened:

April 12, 1948Artists Represented:

Willem de KooningImportance:

On display at this exhibition were 10 of de Kooning's early black-and-white paintings, all priced between $300 and $2000. The show was well attended by New York artists who had been discussing the work of de Kooning for some time but previously had few occasions to view it; for some the Egan show was their first chance, and they loved it. The general public and many critics, however, did not attend. One of the few critics who did visit was Clement Greenberg, who wrote in the The Nation, "..this magnificent first show [confirms de Kooning as] one of the four or five most important painters in the country." When not a single painting sold after a month, Egan decided to extend the exhibition for a further month. In the end only a single painting sold; de Kooning's Painting (1948), which was purchased by MoMA for $700. Quotes

"He told us he couldn't stand working there. He said, '[Neumann] won't let me talk. He said that I have to dress nice and if someone talks to me I'm supposed to look at my shoes.' And we said, 'Why don't you open up your own gallery?'" - Milton Resnick remembering Charles Egan's decision to open his own gallery

"It was a tiny little hole in the wall. He had no storage space, just a closet. He had a little extra square room. That was about all. And the artists fixed it up and painted it."

- Milton Resnick

"Charlie used to go down to Bill's studio early in the morning. Bill had a way of not letting people in when he was working. They'd take walks and talk. Charlie loved to talk about art."

- Betsy Egan Duhrssen, Egan's first wife, discussing his frequent visits to Willem de Kooning's studio

THIS PAGE IS OLD

The Art Story Foundation continues to improve the content on this website. This page was written over 4 years ago, when we didn't have the more stringent/detailed editorial process that we do now. Please stay tuned as we continue to update existing pages (and build new ones). Thank you for your patronage!

WORKS OF ART:

|  |  |

| RESOURCES: Articles about the Charles Egan Gallery  Charles Egan, 81; Art Gallery Owner Helped de Kooning Charles Egan, 81; Art Gallery Owner Helped de Kooning By Bruce Lambert The New York Times March 18, 1993 |

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI