Summary of Francisco de Zurbarán

Sitting in the middle of the "holy trinity" of Seville painters, between the departure of Velázquez for Madrid, and the ascendency of Murillo, Zurbarán occupied the role of the Spanish City's "official painter". The majority of his paintings belonged to Spain's devotional religious style to which he brought elements borrowed from his studies of Caravaggio. His painting was unique inasmuch as it blended a direct approach to his religious subjects with a penetrating aura of spirituality. Later in his career he was commissioned (his only royal commissions) to paint mythological scenes for Philip IV's Buen Retiro palace in Madrid. Having then produced a series signed "painter to the king" for the Carthusian monastery at Jerez, and having decorated a ceremonial ship presented to the king on behalf of the city of Seville, he fell out of favor and legend has it that he spent his last years in Madrid living in poverty.

Accomplishments

- Zurbarán's style was well equipped to tackle portraiture and still lifes but he found his true vocation in religious subjects. His approach to the somber, monastic Spanish Baroque elevated his painting above many of his contemporaries by virtue of the fact that he imbodied his saints, friars, and apostles with a rigid figurative modelling and a refined naturalistic simplicity.

- Zurbarán became well known for the way he created emotional effects by creating sharp contrasts between dark backgrounds and light foregrounds. This technique revealed not only the influence of Caravaggio (Zurbarán was sometimes nicknamed the "Spanish Caravaggio") but also the dramatic technique of tenebrism whereby human shapes and facial features are often depicted in shadow. Though unique amongst his contemporaries, his take on his subject matter - where the material coalesces with the ethereal - was still in keeping with the Counter-Reformation theology of seventeenth-century Spain which was invested in the idea of the spiritual presented in the earthly.

- In later works, Zurbarán would place his religious and mythological figures within the landscape. Though not a landscapist per se, his mature works reveal an affinity with his natural environment and a deft hand when rendering nature as a narrative feature. Such a strategy merely cemented Zurbarán's Counter-Reformation worldview: just as the spiritual exists in the corporeal, so the heavenly finds its expression in the natural world.

- Though Zurbarán carried the earnest storytelling legacy of the Baroque into his later devotional paintings, his figures become more idealized - more mythical - and less realistic in form. This shift was not met with universal approval, however, with some historians suggesting his later work had sacrificed their palpable aura of spirituality for a wistful sentimentality.

The Life of Francisco de Zurbarán

Shining star of the Spanish Golden Age, Zurbarán was one of the most skilled painters of the 17th century. His compelling use of tenebrism is showcased here in the faces of the monks in his masterwork: St. Hugh in the Refectory of the Carthusians.

Important Art by Francisco de Zurbarán

Crucifixion

Most of Zurbarán's output was produced for religious organizations in Seville. Crucifixion was commissioned by the San Pablo el Real monastery. Here Christ is nailed to a cross set against a blank black background.

This work is thought to be the artist's earliest known take on a subject that would become a theme throughout his oeuvre. Indeed, according to curator Almudena Ros de Barbero, Zurbarán "executed some thirty works on this subject" though these fall into two categories: "the Christs who are still alive and taking their last breath [...] and those [Christs] who are dead".

Here, an example of the former, we see the emergence of the Baroque style for which Zurbarán would eventually become world renowned. The intensity of the moment and the agony of Christ is present, not just in his expression, but also in the way Zurbarán rendered the figure bathed in the light emanating from his pale skin and from the white linen wrapped around his waist. These features foreground him in sharp contrast to the black background against which he is placed. According to the exhibition description for this painting at the Art Institute of Chicago, Zurbarán "envisioned the crucified Christ suspended outside of time and place. Conforming to Counter-Reformation dictates, the artist depicted the event occurring not in a crowd but in isolation. Emerging from a dark background, the austere figure has been both idealized in its quiet, graceful beauty and elegant rendering and humanized by the individualized face and insistent realism".

Oil on canvas - The Art Institute of Chicago

Saint Serapion

In this highly dramatic painting, Zurbarán's canvas is filled with the figure of a young friar dressed in a white robe. His arms are extended above his head, tethered by ropes that have been tied to his wrists. His lifeless head hangs to his right resting on his shoulder. On the far right of the canvas is a small piece of paper on which the words "B Serapius" (Blessed Serapius) are written, effectively providing a record of the holy man's identity. Considered one of Zurbarán's most well-known works, Saint Serapion lionizes a religious Martyr whose demise came, according to most historians, at the hands of English pirates.

There is a quiet dignity to Saint Serapion who seems at peace with death; this despite his horrific suffering which included beatings, disembowelment and dismemberment. The way in which Serapion is rendered provides a first-class example of the style in which Zurbarán tended to approach such subjects. According to art historian Odile Delenda, "The painter never liked to make specific reference of the horrific aspects of violent death, and here conceals the martyred saint's body beneath the beautiful white habit of the order. Recalling that of a crucified Christ, the victim's head hangs over his right shoulder in a masterfully achieved expression of abandonment, acceptance, and serenity".

In choosing to avoid the more violent elements of Serapion's death, Zurbarán achieves a different, but equally compelling, scene whereby the spectator's gaze is directed, not to the horror of his injuries, but rather to the face of the friar. The drama of the scene, meanwhile, comes via the use of the sharp contrast between the dark background and the friar's white robe. This technique became something of a feature in Zurbarán's work, revealing once more the influence of Caravaggio on his work.

Zurbarán's gentler, more human approach in rendering Serapion (one of his many monk paintings) would be looked to for inspiration two centuries later. Art historian Jonathan Brown asserts that, "Zurbarán's continuing relevance to modern art is witnessed in [Paul] Cézanne's Uncle Dominick as a Monk of c. 1866 [...] which seems to synthesize the portraits of white-robed monks. It is fitting that Cézanne, whose painting is prerequisite to our appreciation of Zurbarán, should himself have acknowledged a community of artistic spirit with this great Spanish artist".

Oil on canvas - Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut

Hercules Staying the Course of the River Alpheus

Here Zurbarán gives us a near nude Hercules standing on an outcropping of rock with left arm outstretched, resting on a walking stick. His head is turned over his right shoulder as if engaging the viewer. Dominating the background is a thunderous river. Something of a rarity in Zurbarán's career, this painting has as its subject a non-Christian theme. Part of a series of ten paintings depicting the labors of the mythological god Hercules; the theme here is of his fifth labor, one of a series of punishments he was tasked with completing in order to return to the king's good graces. In this particular labor he was forced to clean the stables of King Augeas, a complicated task as the stables held more than 1,000 cattle and had been untouched for thirty years.

Zurbarán chose to depict the moment that embodies Hercules's intellect and cunning where he decided to alter the direction of the Alpheus River so it would flow through the stables washing them out in one swift pass. Zurbarán's choice to depict this element of the labor was a wise one as he was able to demonstrate his mastery of the landscape. Art historian Odile Delenda asserts, "this canvas is one of the most noteworthy of the series on account of its magnificent river landscape. The composition, the perspectival effects, and the lighting are masterfully achieved, especially if it is taken into account that the painting was intended to hang very high and be viewed from below".

Though he did not, as a rule, benefit from royal patronage, this series of paintings was produced for the new royal palace in Madrid. Furthermore, this series provided a rare example of Zurbarán's ability to possess his works of contemporary political messages: the labors of Hercules standing as a metaphor for the unassailable power of the Spanish king. Indeed, according to Delenda, "the scene is steeped in symbolism [...] Here the filth of King Augeas's stables represents the ills that were plaguing Spain, which it fell to the country's powerful rulers to eradicate".

Oil on canvas - Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, Spain

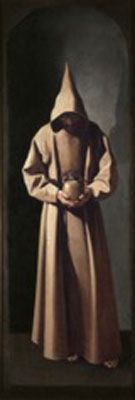

Saint Francis Contemplating a Skull

Originally believed to be part of an altarpiece, this work, like so many of Zurbarán's religious paintings, demonstrates the artist's ability to capture the spirituality of his subjects. As the title confirms, Zurbarán's painting depicts Saint Francis wearing the brown habit typical of the Franciscian Order. Dominating the canvas, he stands with his hood-covered head, shadows obscuring his face, bent looking down at a human skull which he holds in front of him at waist level.

Zurbarán's mastery of the dramatic effects of the Baroque style is reflected in his contrast of light and dark seen here in the shadows which surround the figure and the wash of light that serves to draw the viewer's eyeline up from the skull to Francis's meditative face. Acting as a memento mori, the skull in Francis's hands is a comment on the crucifixion. Indeed, meditation on death was a favoured theme amongst Jesuits, and saints contemplating skulls was something of convention of seventeenth-century Italian and Spanish painting. According to the descriptive text that complements the painting at the Saint Louis Art Museum, "the saint's downcast gaze and shadowed face remove him from the viewer's realm, making his contemplation of the skull a compelling model of religious devotion".

The simple intensity of Zurbarán's treatment of Saint Francis had a strong influence on the Impressionist Édouard Manet. According to art historian Jonathan Brown, Manet's "anachronistic Kneeling Monk of 1865 [...] is a virtual paraphrase of Zurbarán's Saint Francis Meditating [while even] the most radical aspect of Manet's painting, its flattened, undefined space, only emphasizes Zurbarán's suppression of illusionistic depth"

Oil on canvas - Saint Louis Art Museum, Saint Louis, Missouri

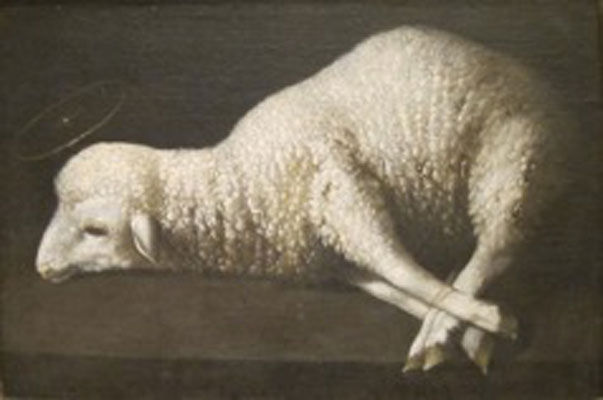

Agnus Dei

Zurbarán's painting Agnus Dei features a lamb with its four legs, bound together at the hoofs, resting on a plank of wood. Set against a blank background, there is, barely visible on the left side of the canvas, a golden ring-like halo hovering above the lamb's head.

Although this is a still life, this painting incorporates the religious theme for which Zurbarán was best known. As the title reflects, and the words inscribed at the bottom of the canvas "Tanqvam Agnus In Occisione" reinforce, the lamb is a metaphor for the persecution of Jesus Christ. The animal is rich in symbolism and according to curator Almudena Ros de Barbero, "The yeanling, with its legs bound together, lies abandoned on a wooden slab that recalls Christ's cross". In rendering the lamb in this way, the artist creates a visual foreshadowing of the death that Christ will suffer through his crucifixion. The intensity of the scene, and thereby the monumentality of Christ's sacrifice is made greater by a common motif in Zurbarán's oeuvre; his amazing skill at creating a sharp contrast between light and dark present here in the black background against which the white lamb rests which might arguably even be interpreted as a representation of good (Christ) and evil (Satan and the ills of the world).

Oil on canvas - Museo de la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Madrid, Spain

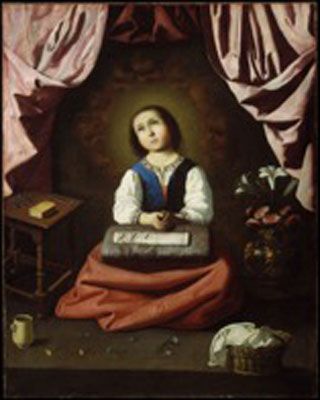

The Young Virgin

The Young Virgin features, in the center of the canvas, a young girl seated on the ground, hands clasped in her lap looking upward. Barely visible, surrounding her head is a semicircle of cherubic angels. A domestic scene, in Mary's lap rests a piece of fabric in which a threaded embroidery needle is resting upright, awaiting her next stitch.

This work is an important example of the many paintings Zurbarán created as private commissions. According to curator Almudena Ros de Barbero, this painting represented the first in this style for the artist: "scenes of the holy childhood of the Virgin and Jesus". Here, as in so many of his works, one finds a rich stream of symbolism including, as Ros de Barbero observed, "the jug of water, the basket with the white cloth, and the flowers at the Virgin's feet" all of which "symbolize purity, loyalty, and spiritual maturity". Furthermore, the "book of sacred writings on the table to Mary's right denotes her life of prayer, and to her left, the richly decorated vase of flowers [...] symbolizes her virtues".

The Baroque style of the period proved the perfect means by which Zarbarán could render his religious scenes. That this image amounts to more than a young girl at work - she is rather the embodiment of the most holy female in the Christian faith - is made by Zurbarán through the high drama of a soft glowing light that reflects off her face and surrounds her head in a halo-like fashion. This serves to make Mary's holiness clear as she looks upward from her domestic responsibilities towards heaven foreshadowing the future connection she will have with God and the important role she will play in the life of Christ.

Oil on canvas - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

Jacob

In this painting Zurbarán depicts the biblical figure of Jacob as an old man with long, gray beard. Head bent and back stooped, he rests with hands clasped on his walking stick. His attire is rich in color and includes a blue shirt and red vest along with a cream colored turban with scarf that wraps around his neck and hangs down his chest. The leather sandals he wears are fitting for the pastoral background in which he stands. This painting, one of a series of thirteen works, is an epic achievement of individual life-size portraits that feature not only Jacob, but each of his twelve sons too. Once more, Zurbarán has taken his subjects directly from stories in the bible (here the Old Testament book of Genesis).

In describing the significance of these works, critic Peter Schjeldahl writes, "they constitute a terrific feat of Baroque storytelling: movies of their day. All the characters - each a distinct personality uniquely posed, costumed, and accessorized, and towering against a bright, clouded sky and a low swath of sylvan scenery - appear to be approximately as old as they are in the forty-ninth chapter of Genesis. There the dying Jacob prophesies, in gorgeous verse, the fates of the founders-to-be of the Twelve Tribes of Israel".

Standing as prime examples of his mature style, this series show clearly Zurbarán's command over the figure. In addition, however, these works highlight another of his artistic skills which is often less acknowledged, his skill at rendering nature. According to historian Jonathan Brown, "although Zurbarán painted no independent landscapes, he became the master of a type of landscape background almost from the start of his maturity." Here his command over the subject, as the finely rendered background indicates, help to place the figures more solidly within their biblical narratives.

Oil on canvas - Collection of Auckland Castle, Bishop Auckland, England

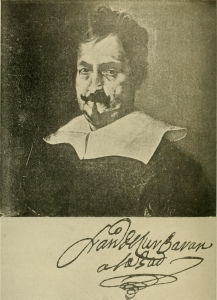

Biography of Francisco de Zurbarán

Childhood and Education

Francisco de Zurbarán was born in the small Spanish town of Fuente de Cantos to the merchant Luis de Zurbarán and his wife Isabel Márquez. He was the youngest of six children - four brothers and a sister - but little else is known about his childhood. It seems, however, that Zurbarán must have demonstrated an aptitude for drawing at an early age given that his family was willing to support his pursuit of art as a career. While some biographical accounts suggest that he may have first studied under a local artist, records show that in January 1614 his father arranged formal training for him in Seville where he entered into a three-year apprenticeship. Under the guidance of Díaz de Villanueva, Zurbarán interacted with leading artists of the day including Francisco Herrera the Elder. It was in Seville in fact that he formed what would become a lifelong friendship with fellow student Diego Velázquez. It is true that Velázquez was/is considered the greatest painter of Spain's Golden Age, but Zurbarán was/is considered more representative of the period given that Velázquez would work exclusively for the royal court in Madrid whereas Zurbarán (before joining his friend later in his career) consistently produced ecclesiastical and monastic subjects for his patrons in the south (the heartland) of Spain.

Zurbarán's early training had a lasting impact on the direction of his art. According to art historian Odile Delenda, "the workshops of Seville were extremely busy at the time due to the demands of the religious orders to decorate their new ecclesiastical buildings and also to renew the ornamentation of the established houses in conformity with the dictations of the Council of Trent". It was by executing these religiously themed works that Zurbarán learned his craft. Indeed, he would tackle religious themes throughout the majority of his career even though historians have been left puzzled as to whether or not the artist was himself a man of devout faith. Having had a practical, rather than academic, training, however, Zurbarán's mature style was honed by assiduously studying the works of past masters, not least the works of Caravaggio.

Mature Period

On the completion of his apprenticeship in 1617, Zurbarán turned down the opportunity to enter Seville's city guild of painters choosing instead to return home where he established a business as a painter in the town of Llerena. Though his business thrived, his personal life was beset with tragedy. His first marriage to María Páez Jiménez, a woman nine years his senior, in 1617, lasted just six years due to her premature death. María left her husband with three young children, including a son Juan, who would also become an artist. In 1625, shortly after María's death, Zurbarán married another older woman, Beatriz de Morales, who came from a wealthy family. However, their only child, a daughter, died in infancy.

Still early in his career, Zurbarán received important commissions from religious groups including an early request in 1626 for fourteen pictures for the Dominican Order in Seville. In 1628, after accepting a commission to paint a series of twenty-two paintings of the life of Saint Peter Nolasco, he moved to Seville and lived in that monastery with his assistants while completing the commission; and then, following the promise of more work, he permanently relocated his family to the city. Once settled in Seville, evidence of Zurbarán's growing independent streak started to reveal itself. In 1630 he refused to sit the exam necessary for admittance into the Seville Guild of Painters, seemingly unwilling to submit to the "petty" behavior of the city's artistic elite. His reputation had grown enough however that the City Council continued to support him on the grounds that it was more advantageous to have a painter of such skill and vision working in Seville.

In the immediate years that followed, Zurbarán secured a number of important commissions. While these were mostly religious in nature, he was invited to Madrid where he undertook the task of decorating the Great Hall of the royal palace. As a guest of his old friend Velázquez (who was directing the project), he worked on mythological paintings that were analogous with the King's glory. Legend has it that so impressed was he with Zurbarán's contribution, Philip IV placed his hand on the artist's shoulder and declared "Painter to the king, king of painters".

Unfortunately, the ebb and flow of artistic success and personal tragedy continued to affect Zurbarán. Political troubles in Seville had already resulted in a reduction of local commissions. But, with the assistance of his son, Juan, Zurbarán looked to the Americas and the Spanish colonies - including Argentina and Peru - for new markets. While this new enterprise proved prosperous, it was offset by further personal tragedy when his second wife died in May of 1639. Five years later, a 46-year-old Zurbarán entered into his third and last marriage to Leonor de Tordera, a widow who was eighteen years his junior. She would give birth to six children, but only one, a daughter, would survive beyond infancy. Zurbarán's terrible personal loss was only compounded in 1649 when Juan lost his life to the plague which was ravaging Seville.

Later Period

During the last decade of Zurbarán's life, his beloved city of Seville become less receptive of his work as his style fell out of favor due to the rising popularity of other Spanish artists, notably Bartolomé Esteban Murillo. Seeking a change of fortune, he relocated his family to Madrid in May of 1658. Joining a circle of fellow artists, including his friend Velázquez, Zurbarán received some royal commissions, and requests from individual patrons looking for paintings for their private religious devotions, but he failed to recapture his earlier success. His financial situation duly declined which, according to Odile Delenda, "seem to have mainly derived from the difficulty he had in getting paid by his debtors".

Zurbarán's health declined significantly in his final years. It is believed he was forced to stop painting in 1662 causing further financial strain on his family. It is generally thought (though some accounts query this assumption suggesting rather that his estate was valued at 20,000 silver reales) that his dire financial situation was exposed in the will he drafted on the day before his death. According to art historian Jonathan Brown, "[the will] is short because the painter had little to leave his heirs except three small debts still owed him. He bequeathed the money from them to his wife, together with the 'few possessions that we have,' which were to be auctioned for his widow's benefit".

The Legacy of Francisco de Zurbarán

Zurbarán's legacy has followed an uneven trajectory in the history of art. According to Jonathan Brown, his "powerful, monumental style held no appeal for [an eighteenth century] Rococo audience, [and] many of his best works were hidden from view in the monasteries and churches that had commissioned them". Opinions changed, however, when his work began to be recognized during the beginning of the 19th century. According to Brown once more, two key historical events - "the Peninsular War (1808-14) during which French generals looted the churches, monasteries, and convents of Andalusia and appropriated paintings for their private collections [and] the Secularization Act of 1835, which disestablished Spain's monasteries and caused the dispersal of their artistic fittings and decorations" - directly benefited his legacy by allowing Zurbarán's art to gain a wider visibility in the international art world.

For contemporary audiences, Zurbarán's place is secured as a leader of seventeenth century Baroque art, and one of the great artists of Spain's Golden Age. Two centuries on, his work, and attitude, would inspire the first generation of Modern artists. Brown asserts that, "to [Jean-François] Millet, [Gustave] Courbet, [Théodule] Ribot, and others, Zurbarán furnished a model of nonacademic art. His willingness to ignore the conventional rules of painting [...] and his refusal to follow a classical conception of man and nature encouraged painters who themselves wanted to approach their art with a fresh eye".

Influences and Connections

-

![Caravaggio]() Caravaggio

Caravaggio -

![Albrecht Dürer]() Albrecht Dürer

Albrecht Dürer -

![Diego Velázquez]() Diego Velázquez

Diego Velázquez - Alonso Cano

- Francisco Herrera the Elder

- Don Diego de Cárdenas

-

![Paul Cézanne]() Paul Cézanne

Paul Cézanne -

![Gustave Courbet]() Gustave Courbet

Gustave Courbet -

![Édouard Manet]() Édouard Manet

Édouard Manet - Pedro de Camprobín

- Alonso Cano

- Don Diego de Cárdenas

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI