Summary of Pieter de Hooch

De Hooch is renowned as a painter of interiors and courtyards featuring sophisticated spatial arrangements and virtuoso atmospheric lighting effects. With contemporaries Gerrit Dou, Gabriel Metso and Johannes Vermeer, he played a central role in the promotion of Dutch genre painting during the seventeenth century. Almost habitually compared to Vermeer, historians are apt to debate who exerted more influence over who, though de Hooch, though less gifted, was undoubtedly the more versatile and prolific of the two Delft painters. For all his famous colleague's superior handling of the adult human figure, it is de Hooch who emerges as the painter of children and as the "master of interiors". He created unsentimental vignettes acted out in courtyards and superbly furnished rooms realized through fine attention to detail and complex picture perspectives that typically featured his signature doorkirkjie - or "see-through-doorway" - technique. Though the intimate quality of his work deteriorated in later years (a decline that has been attributed to a series of profound personal tragedies), he remains one of the most important figures of the Golden Age of Dutch painting.

Accomplishments

- De Hooch's works, which were generally small in size, revealed the artist's finely nuanced observation of the fleeting details of everyday living; his cultured treatment of color and light and his variations in tone and perspective making him comparable only to Vermeer. The artist's virtuoso command of perspective and responsiveness to light intensity was unprecedented in seventeenth century Dutch painting and set new standards of authenticity for interior domestic narratives.

- Creating what were, in effect, "pictures within pictures", de Hooch is considered the pioneer of the doorkirkjie technique. Complementing the main picture narrative, his "see-through" doors expanded the scope of the picture plane to offer a more involved method of storytelling. Indeed, by offering the viewer a glimpse of the architectural world adjacent to, but beyond, the walls of the interior space he provided inspiration for many of his contemporaries.

- In General, de Hooch adopted a straightforward approach to his subject and did not resort to moralizing or symbolic excesses. Though they are intimate and kindly in character, often focusing on women and children for their human interest, his best works brought a new level of respectability to the genre which had historically treated such material with a mawkish sentimentality.

- De Hooch's exquisite handling of lighting effects are abundantly evident in his skill of creating the illusion of looking into a living domestic space. He was a trailblazer in capturing light on ceramics, polished wood and glass but the artist had a specially fine eye for slightly crumbling exterior walls that revealed exposed areas of mortar. As Sue Herdman, Editor-in-Chief of The Arts Society Magazine, noted, de Hooch "'builds' his house on canvas, one brick at a time, each just centimetres large, using the tiniest brush strokes of red paint".

The Life of Pieter de Hooch

Pieter de Hooch is best known for his skill at rendering domestic interiors, and for his invention of the doorkirkjie, or “see-through-doorway", technique, bringing the exterior world into the frame, thus emphasizing the home as a safe haven for families to live out their pious lives.

Important Art by Pieter de Hooch

The Empty Glass

De Hooch's early paintings, known as "koortegardje" pictures, showed scenes of disorderly soldiers in stables and taverns depicted through shades of dark browns and yellows. The Empty Glass painting shows just such a tavern interior. In the foreground, a seated soldier, who appears drunk (due to his red nose and overly jovial expression and gesture) is handing his empty glass to a barmaid who holds a pitcher of wine. In the dark background of the tavern sit two men playing cards. On the floor lays discarded playing cards and cigarettes.

Although these works bear the hallmarks of Dutch painter Adriaen van Ostade, de Hooch used the genre to finesse his skills in lighting, color, and perspective. Comparisons have also been drawn between his works and the tavern interiors by his contemporaries, Gerard ter Borch, Gerbrand van den Eeckhout, Ludolf de Jongh, and Pieter Codde, particularly in terms of the palette of browns and yellows, and the painting's chiaroscuro effects.

Shortly after he produced this work, De Hooch moved to Delft, where he abandoned tavern scenes in favor of the popular genre paintings and domestic scenes. His domestic scenes were characterized by quiet and order, and served as models for a fully realized Calvinist family life. What citizens of the newly independent Dutch Republic wanted were not scenes of rambunctious drunkards, but images that foregrounded the importance of the stable family unit, which was seen as foundational to the health and resilience of the Republic.

Oil on panel - Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

The Courtyard of a House in Delft

In this work, the setting is an interior domestic courtyard. A woman and a young girl enter the courtyard hand in hand. The pair look lovingly into one another's eyes suggesting a mother/daughter relationship. To their right, we look through a brick and stone archway onto an open doorway, where another woman, dressed in black and red, stands with her back to the viewer looking out onto the adjoining street. Above the archway, a stone tablet in the wall reads "This is in Saint Jerome's dale, please be patient and meek, for we must first descend, if we wish to be raised. 1614″. On the floor of the courtyard lie a broom and bucket. To the top right, blue sky and fluffy white clouds can be seen.

Around the mid-1650s, de Hooch stopped painting soldiers and peasants, and began to focus instead on domestic scenes featuring the middle classes engaged in quotidian activities. In most of these works, the interaction between the figures is restrained, giving the scenes a sense of stillness, and in the case of mother-child tableaux (of which he painted several), a sense of intimacy. Art historian Simon Schama asserts in fact that de Hooch provided "the first sustained image of parental love that European art has shown us".

These domestic interiors are considered to be de Hooch's greatest works, and were popular subjects for many Delft School painters, and Golden Age Dutch painters generally. Curator Alejandro Vergara suggests that de Hooch's work shows the influence of Nicolaes Maes, "Particularly the dignity of the treatment of domestic subjects, [...] and above all, the geometry of the spaces and the warmth of the light which illuminates them". Vergara adds that de Hooch organizes space "following a strict geometry" and that in his works, "light plays a key role, creating strong contrasts between the illuminated areas and those left in shade and emphasizing the differences between the various materials".

Oil on canvas - The National Gallery, London

A Woman Preparing Bread and Butter for a Boy

This painting, one of few surviving works from de Hooch's early years in Amsterdam (before the deaths of his wife and two of his children), shows a domestic interior, with a doorkirkjie to the left leading out to the street. To the right are a seated woman dressed in a black jacket and blue skirt, and a young boy standing to her right, wearing red and clutching a hat under his folded hands. The woman has a loaf of bread on her lap, and is carving a piece of butter from a plate on a chair to her left. The boy's folded hands indicate that he is saying grace before receiving his morning meal. We can assume that after eating, he will head to the school visible through the doorkirkjie.

De Hooch and his contemporaries often included simple symbolism in their domestic interiors in order to convey moral lessons regarding education, child-rearing, and the importance of keeping busy. In this painting, for instance, the books and candle in the niche above the doorway symbolize enlightenment through education. The small top lying on the floor in front of the door likely refers to a Dutch proverb that states that a child and a top will both fall idle unless continually "whipped" (a toy spinning top that has to be "spun" by striking it with a stick).

In de Hooch's work, his meticulous rendering of architectural elements like brick and stonework indicate that he learned some aspects of masonry from his bricklayer father. But these elements can also be read for their moral and religious overtones by communicating the importance of maintaining order and simplicity within the private home. The interior space is dark, moreover, and this contrasts with the daylight spilling through the front door. The dark interior connotes, perhaps, the importance of leading a still and deferential life.

Oil on canvas - Getty Center, Los Angeles, California

The Council Chamber in Amsterdam Town Hall

De Hoochshows one of two mayor's rooms of Amsterdam Town Hall, with its patterned black and white marble floors, high ceiling, double bay windows, and impressive chimney-piece with a cornice and frieze supported on pilasters. To the left, we see a second room and window through an open doorway. The upper-left section of the image is dominated by a red curtain. The painting serves as an important historical document as it faithfully represents the day-to-day activity in the city's civic offices.

Several figures populate the scene, all of whom are upper/middle-class individuals and families enjoying their visit to one of Amsterdam's most important buildings. To the left, a woman dressed in red and yellow holds hands with a man dressed in black who gestures with his left hand at the vaunted ceiling. They appear to have just arrived. At the centre, in front of the fireplace, is a group of people that includes two men, one woman, and three children. In front of them is a dog. To the right stands a solitary man carrying a stick facing the viewer, and behind him, a solitary woman, seen in profile, gazing out the window.

During the 1660s, De Hooch began to paint for wealthier patrons in Amsterdam, and he became known for his "merry company" scenes and family portraits in opulent interiors (as opposed to his previous domestic interiors), with marble floors and high ceilings (influenced by an increasing taste for French art and culture). Amsterdam's Town Hall became one of his favorite settings (the building also appeared in his Musical Party in a Hall (1663-65), and Going for a Walk in the Amsterdam Town Hall (1663-65)). This painting exemplifies de Hooch's talent for using various lighting sources to create a play of shadows. The work also demonstrates de Hooch's skill in architectural views and perspective, something he likely learned from Carel Fabritius.

Oil on canvas - Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, Spain

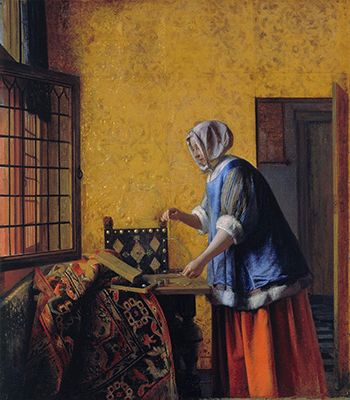

Interior with a Woman Weighing Gold Coin

In this mature work, a wealthy woman, signified through her blue top trimmed with fur and her fine red skirt, stands in front of a small table, holding a small scale with her right hand, and picking up coins with her left. A patterned carpet is hung over the corner of the table. The wall behind the woman is painted vibrant gold. To the right is an open door, through which we see another room and a second closed door. To the left of the frame, finally, de Hooch paints an open window.

According to curator Alejandro Vergara "The quality of light in [de Hooch's] paintings and the pleasure with which he recreates the textures and the beauty of everyday objects contributes to the welcoming, comforting mood of his interiors. The great innovation of de Hooch's painting is the importance which it gives to the middle-class setting, while its most unique quality is the absolutely convincing naturalism of his paintings which rely on the treatment of light and space and the psychological proximity of the figures. As we stand before one of De Hooch's paintings, we feel that we have stepped inside a seventeenth-century home".

This painting is frequently compared to Johannes Vermeer's Woman Holding a Balance (also from 1664). Indeed, many of de Hooch's and Vermeer's works are similar in style and subject matter, and scholars continue to debate which artist exerted the greater influence over the other. Study of this work and its preparatory drawings indicates that de Hooch's slightly pre-empts Vermeer's painting. Vergara argues that "De Hooch's sensibility towards the effect which the representation of space has on the psychological mood of a painting may have influenced Vermeer. Other shared features such as their interest in describing textures and the effects of light on materials, are the result of shared sensibilities which they must have mutually reinforced".

Oil on canvas - Gemäldegalerie, Berlin, Germany

A Musical Party in a Courtyard

In A Musical Party in a Courtyard, three people (two women and one man) are seated in a dark courtyard, enjoying their leisure time together. The woman at the far left plays a violin. The man smiles at the second woman. The figures all wear fashionable clothing and fine jewelry, and on the table lays an expensive Turkish rug. A fourth figure, with his back to the viewer, stands in the arched doorway at the right of the frame, looking out at the street, the canal, and the houses beyond.

Despite the opulent elements (the carpet, clothing, and jewelry) depicted in this painting, de Hooch does not render the courtyard architecture in any detail, instead giving us only a glimpse of the area. Curator Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. writes that, by the 1670, "De Hooch's work had lost much of its delicacy and finesse. His later compositions be¬came grander and more contrived, and his color harmonies and light effects harsher". The only section of this work which bears the lightness and fine detail of his earlier masterpieces is the city view seen through the doorway. It is generally surmised that the quality of de Hooch's work suffered due to his grief and anguish following the death of his wife and two of his children in the 1660s.

Oil on canvas - The National Gallery, London

Biography of Pieter de Hooch

Childhood

Little is known about de Hooch (sometimes spelled Hoogh) since only a handful of documents directly connected to him are known to historians. It is agreed however that he was the eldest of five children and was baptized on, or shortly after, his birth date in the Reformed Church in Rotterdam. His father was a master bricklayer (who may have had a influence on his son's painterly interest building materials such as brick and tile) while his mother, a midwife, passed away when her children were very young. It is also known that de Hooch outlived all four of his siblings.

Education and Early Training

Though the exact dates are not recorded, de Hooch served his apprenticeships under two painters, the "vroedschap" ("wise man") Ludolph de Jongh in Rotterdam, and later, Nicolaes Pietersz Berchem, one of the leading Dutch painters of Italianate landscapes, in Haarlem. While at Haarlem he befriended fellow pupil Jacob Ochtervelt, himself destined to become the leading specialist in aristocratic genre painting. De Hooch showed little or no interest in landscapes, however, with all his early paintings being so-called "koortegardje" pictures: scenes of rowdy soldiers in stables or taverns rendered in shades of dark browns and yellows. He soon graduated to "kamergezichten" ("room-views") featuring middle-class subjects in informal conversation. He appears to have drawn inspiration from Hendrik Sorgh, a fellow Rotterdam painter known for his skill in organizing figures in interiors.

It was commonplace for artists of the day to have a second trade and, in 1650, de Hooch began working as a painter and dienaar (servant or assistant) for the Rotterdam linen merchant and art collector, Justus de la Grange. His work involved accompanying de la Grange on trips to The Hague, Leiden, and Delft. As well as learning the cloth trade, it is believed that De Hooch exchanged many of his early works (at least eleven paintings) for housing and other benefits. In 1652 de Hooch relocated to Delft where he met and married (in 1654) Jannetje van der Burch. Pieter and Jannetje (very probably the sister of the painter Hendrick van der Burch) had seven children.

Mature Period

De Hooch entered the guild of Saint Luke in Delft as an independent painter in 1655 and is recorded as having paid dues in 1656 and 1657. He studied under guild painters Carel Fabritius and Nicolaes Maes, and, given the many similarities in their painting style, there is universal agreement that he crossed paths with Johannes Vermeer (who also lived in the Delft municipality). Like Vermeer, de Hooch produced small works, and, like Vermeer, his painting displays an elegant finish and a tremendous compositional poise. But while it is known that Vermeer worked with a camera obscura, there is no evidence, especially in his most famous Delft works, that de Hooch was interested in using optical devices to perfect his images.

Because of their similarities, the relationship between de Hooch and Vermeer has, down the years, been the source of considerable debate among art historians. It was assumed throughout the nineteenth-century that de Hooch had been influenced by Vermeer, but that view has been reassessed. According to the art historian Johnathan Janson, "Vermeer's early works of the 1650s reveal little interest in the developments that were revolutionizing Dutch genre painting [and it] was not until 1657 that he painted his first known genre interior, A Maid Asleep, in which he made a 'superficial adaption' of the innovative motifs developed in Delft [by de Hooch]". Janson adds, however, that "given the paucity of historical evidence it is not out of the question that Vermeer led the way on some occasions while in others, De Hooch [led the way]. Whatever the case may be, although the art of de Hooch may appear today as wanting in intellectual profundity and philosophical implications (and perhaps ambition) when compared to the art of Vermeer, de Hooch was unquestionably the more prolific and versatile painter of the two".

With his Delft colleagues, de Hooch came to the fore at a pivotal moment in the forming of the new Dutch Republic. Although liberation from Spain was declared in 1581, the Spanish state did not formally recognize Dutch independence until the end of the Eighty Years War in 1648. With religious tensions playing such a significant role in the conflict, art in the newly independent Republic (where Protestantism had replaced Catholicism) became a vital tool for national self-identity. In the period that became known to art history as the Dutch Golden Age, a uniquely indigenous art helped the Republic reinvent itself and to celebrate: its newfound religious freedom; its military might; its scientific skill; and its political independence. Though one can certainly find traces of ideological themes in the works, Golden Age art supported the idea of secular enlightenment and rejected outright extravagant treatments of biblical parables.

By the turn of the sixteenth century, the Dutch Republic had become an important colonial power, with the world's first multinational corporation, the Dutch East India Company, forming as early as 1602. The nation prospered economically through trading relations with Europe, the Baltic States, Asia, and also from its colonial expansion into the Americas and its strong stake in the slave trade. At the same time, a large number of highly educated and highly skilled Protestant workers migrated from the Habsburg territory to the Dutch Republic, helping to further drive economic prosperity. It was the new merchant classes that became the primary consumers of art, and their preference was for still lifes, landscapes, and genre paintings.

De Hooch was by now experimenting with his doorkijkje ("see-through door") technique that extended the narrative space from one room to the next, or often out onto the adjoining street, through a series of open doors and/or windows. The home became a vital symbol of Republican culture and de Hooch's pictorial device showed a way to juxtapose the calmness and order of private life against the chaos of the public world. Indeed, the new Dutch society was placing great value on the home and the family as the source of moral education. As art writer Allen Hirsch explains, "People worked hard and when they returned home, they wanted a reminder of the true fruits of their labor: their home life [...] the sacred was now the domestic". Curator Walter Liedkte added that in de Hooch's paintings, "the interior itself seems to promise comfort and protection, while the light stroking (as if feeling) different surfaces suggests pleasure in the beauty of ordinary things".

It was between the years 1655 and 1662 that de Hooch came of age as an artist and his work reached its peak of excellence. Though he would occasionally paint open-air scenes, almost all of his mature paintings were unsentimental interior and courtyard scenes, typically featuring two or three figures engaged in everyday domestic activities. There is, evident in paintings such as The Courtyard of a House in Delft (1658) and A Woman Preparing Bread and Butter for a Boy (c. 1660), a palpable atmosphere of calm and de Hooch perfected the skill of creating spacious and carefree effects through his masterly control of light, color, and compositional balance. Janson argues that de Hooch's mature works "are often so believable that they appear to be faithful records of actual sites" although they were "in significant part, fruit of the painter's imagination and compositional skill". Commenting specifically on de Hooch's preference for urban courtyards, meanwhile, the art historian Wayne Fantis - who credits the artist with the "invention of one of the most popular motifs in genre painting" - noted that courtyards were an "intrinsic feature of Dutch domestic architecture and were either constructed within the middle of a house or at its very back" where they would "provide light to their interiors". Fantis adds that de Hooch's "representations of courtyards, like his interior scenes, were, ultimately, contrived, skillfully combining direct observation of his immediate surroundings with prevalent pictorial conventions".

Late Period and Death

Though there are no official traces of his movements between 1657 and 1667, all indications are that de Hooch and his family settled in Amsterdam in the early 1660s, most likely due to the greater number of wealthy clientele residing there. Notwithstanding a documented visit to Delft in 1663, it is agreed that de Hooch practiced in the Amsterdam area for the rest of his life.

The move to Amsterdam was blighted by personal tragedy with two of his children succumbing to the bubonic plague. Little else is known of de Hooch's time in the city, other than he had regular contact with the painter Emmanuel de Witte and that he and his family lived (and attended church) on the city outskirts at Westerkerk. Most scholars agree that after his wife died in 1667 (aged 38) de Hooch's work lost much of it tenderness and delicacy. Indeed, his later compositions become more monumental in scale and his colors and lighting effects darker, coarser and generally more stylized. This deterioration in quality was quite possibly due to the grief of being widowed and the stress of raising his children on his own. De Hooch's son Pieter, who was also his pupil, died at Amsterdam's mental asylum in 1684 but how and when De Hooch himself died is unclear, though his last known work is dated 1684.

The Legacy of Pieter de Hooch

Although de Hooch has usually been eclipsed by Vermeer as the greatest Golden Age painter, it was he who did most to popularize genre paintings of domestic interiors and scenes of private family life. De Hooch has been taken to task by some historians for his "less than elegant" handling of the brush and his "below par" technique, but de Hooch's influence is unmistakable in the work of several eminent Northern European painters including Hendrick van der Burch, Ludolf de Jongh, Pieter Janssens Elinga, Esaias Boursse, and even Johannes Vermeer himself; the latter particularly in regard to lighting effects, his use of geometry and perspective, and a focus on domestic familial scenes.

It is perhaps de Hooch's pioneering use of the doorkirkjie - or "see-through-doorway" - that is his most unique legacy. It proved to be one of the most effective ways of achieving pictorial depth within the domestic space and allowed the painter to create more complicated architectural spaces and thus widen the scope for the pictorial narrative. The technique, which was adopted by Maes, De Witte, van Hoogstraten and Vermeer, even allowed for glimpses of city street life to be observed through open doors or windows. Moving beyond the realms of painting, and into the twentieth century, the Italian film director Luchino Visconti was renowned for framing domestic scenes in the "de Hoochian" way.

Influences and Connections

-

![Carel Fabritius]() Carel Fabritius

Carel Fabritius - Ludolph de Jongh

- Nicolaes Pietersz Berchem

- Hendrik Sorgh

- Adriaen van Ostade

-

![Johannes Vermeer]() Johannes Vermeer

Johannes Vermeer - Justus de la Grange

- Nicolaes de Maes

- Emmanuel de Witte

- Delft School

- Hendrick van der Burch

- Pieter Janssens Elinga

- Esaias Boursse

- Luchino Visconti

-

![Johannes Vermeer]() Johannes Vermeer

Johannes Vermeer - Emmanuel de Witte

- Jacob Ochtervelt

- Hendrick van der Burch

- Gerard ter Borch

-

![Dutch Golden Age]() Dutch Golden Age

Dutch Golden Age - Delft School

- Genre Painting

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI