Summary of Ulay

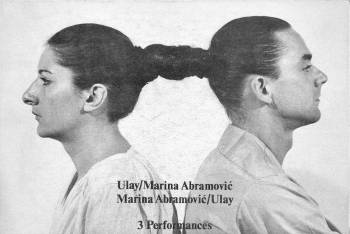

Ulay was a mercurial, multi-disciplinary, and profoundly independent artist, working across the borders of disciplines, bodies, and nations to produce urgent and immediate artworks that asked the viewer to confront what they had once assumed without question about the world around them. He is best-known for his artistic and personal collaboration with Marina Abramović over 12 years from the mid-1970s, performance work which influenced a generation of Performance, Body, and Installation artists and became foundational to an art-world understanding of the power and potential of live performance in a gallery.

Ulay's practice went far beyond this collaboration, however, stretching from an early investment in photography (specifically the Polaroid) as a medium to explore gender and identity, to audacious public interventions like stealing a painting from a national museum and displaying it in the home of a migrant family. After concluding his work with Abramović he produced more photography, sculpture, and installation, and whilst the two ex-collaborators occasionally clashed on the representation of their joint work, Abramović's increased profile led in turn to Ulay achieving an ever greater level of recognition and curatorial respect.

Accomplishments

- Ulay formed with Marina Abramović one of the most important partnerships in the history of Performance Art, and yet has consistently been underrepresented in curatorial representations of their collaboration. This stems partly from his resentment of the commodification and archiving of performance, a process that, unlike Abramović, he largely refused to participate in. He dismissed attempts to "reperform" any of their works (as Abramović has explored), suggesting that their uniqueness, irreproducibility, and resistance to incorporation within a museum is an essential quality of their success as artworks.

- This skepticism of the institutions of the art world extends from museums and their attempts to "capture" performance to art historians and critics, whom Ulay frequently dismissed as lazy. Described by some as having a "secretive" relationship to art history, Ulay insisted that his work was never made for the benefit of art critics or historians and made little attempt to be recognized or included in surveys or retrospectives. This "secretive" relationship could easily be read as a form of Institutional Critique.

- As a consultant for the Polaroid company in the 1970s, Ulay pioneered polaroid photography as a new technique for artists, centering his experimentation around ephemerality and the recording of unique moments, and using the medium to explore gender and those on the margins of society. Whilst not as well-known as some of his performance collaborations, these images would prove to be highly influential in later conversations around the documentation of performance and embodied artistic practices, particularly the notion of "performing to camera".

- Ulay believed profoundly in the social and political efficacy of art, famously stating that "aesthetics without ethics is cosmetics". Much of his artistic practice and personal life therefore engaged with the representation and experiences of marginalized people, from migrant workers in Germany, transvestites in Amsterdam in the 1970s, and Aboriginal Australian people. As with all his work, Ulay invested his own body in this engagement, living amongst these communities, taking on aspects of their lives in his own and committing to a productive and unique artistic dialogue.

- Alongside this interest in cultural and social identities (such as the way that indigenous and non-western societies viewed questions of art and ecology), Ulay's work is also concerned with an internal interrogation of self. This examination of the way that he, and by extension his audience, establish and perform our own identities extends throughout his photographic work, his collaborations with Abramović, and his solo performances and connects his practice to a broader history of Identity Art.

The Life of Ulay

Ulay was born in a German bomb shelter during a WWII air-raid, spent over a decade living out of a van with his lover and artistic collaborator Marina Abramović, and has called himself " a Polaroid child," "a loner who longs for collaboration," "a model of the urban nomad," and the "most famous unknown artist."

Important Art by Ulay

S'he #644

From 1973-74, Ulay produced the series S'he, in which, as art and photography writer Emily Dinsdale explains, he "presented himself as the hybrid-gendered alter-ego he named Renais Sense" (a play on the term "renaissance", meaning "rebirth"). In many of the images, including S'he #644, Ulay photographed himself in makeup and costume, vertically dividing himself into masculine presentation on one side (with stubble, men's clothing, shorter hair, and a rolled cigarette or joint in his mouth), and feminine on the other (cleanly shaven with full makeup, a wig, and women's clothing). He often emphasized that his Polaroid work was "fast, direct, non-mediated," and unstaged, and that, unlike many photographers, he was not concerned with the formal or aesthetic qualities of the images. This body of work was inspired by the transvestite and transsexual communities with whom he frequently interacted during this time, as well as functioning as an exploration of his own concept of self.

Art critic Leigh Markopolis considers Ulay's S'he series to be the work in which he is "at his most beguiling and disquieting," adding that "the characters he presents are expressions of an interior truth, rather than props to catalyze an alternate reality. They appeal because they convincingly seem to represent facets of the artist's personality, documenting them for analysis at a later stage. They are both mirror and reflection." Indeed, Ulay did not think of his early Polaroid work as "art", but instead as "intimate actions, carried out in the absence of a live audience, ephemeral in nature, yet arrested in time. [...] These were very intimate and private works, my business, nobody else's. [...] It was a mirror, a true mirror, but with one main advantage: it kept the images."

Ulay held a performative view of identity that broadly aligns with the more contemporary theoretical work of Judith Butler, arguing that identity characteristics like gender are the produced the repetition of symbolic actions rather than innate truths. As Ulay stated later in life "What I have learned - and it may be the best lesson about identity - is that it is a very easy thing to accept, because you are born with it. You have a national identity, a religious identity, a familial identity, a name identity, everything. But for me [...] identity is change and in my life I have changed many times." Moreover, he saw deep connections between his polaroid work and the performance work he was soon to undertake, even though "performance is ephemeral while Polaroid produces a material object". He stated, "As I began using the Polaroid camera, mainly pointing it at myself - a practice I called auto-Polaroid - I immediately discovered its performative element. I performed in front of the camera, giving priority to the resulting still image."

Polaroid photo - Centre Pomidou, Paris, France

GEN. E. T. RATION ULTIMA RATIO

For this work, Ulay had the words "GEN. E. T. RATION ULTIMA RATIO" tattooed on his lower left arm. Shortly after getting the tattoo, he found a plastic surgeon working at a hospital in Haarlem who agreed to remove the section of skin. The operation took place four weeks after the artist got the tattoo under a local anesthetic. A nurse assisted Ulay in changing the film in his camera as he documented the procedure. The resulting images became a series titled Tattoo/Transplant. Ulay explained that "as you can see in the images, it looked awful, because when you remove the skin, the meat underneath lifts up a few millimeters higher than the skin. It looked disastrous." The surgeon then took a thin layer of skin from the underside of Ulay's forearm, and grafted it where the tattoo had been. Ulay preserved the tattooed skin in formalin for a year, and then took it out, stretched it, air-dried it, and framed it in an ornate golden frame.

Explaining the concept behind this performance, Ulay remarked that he"wanted to expose the art market. [...] There is an expression, to bring your skin to the market, which means to sell yourself. I wanted to bring my skin to the art market." The phrase he had tattooed was derived in part from the French anarchist slogan "Ultima ratio regum", meaning "The Last Resort of Kings and Common Men". This work is generally considered to be one of the first instances of plastic surgery in Performance Art, a strategy that would be later expanded by other performance artists, such as in the work of Orlan and others.

Art critic Leigh Markopolous wrote about GEN. E. T. RATION ULTIMA RATIO, "the gesture most clearly portended an ambivalent relationship with pain. Overall these photographs document and establish the terms of use for his body as a medium as well as a vocabulary of endurance and self-exposure. Individually and in their totality, the images are perplexing; theatrical, yet convincing; tormented, yet uplifting; sexually provocative, yet guileless. Their urgency is conveyed in their volume and their immediacy enhanced by the use of Polaroid." Performance curator RoseLee Goldberg retroactively coined the term "performative photography" to describe Ulay's photos from this early period, recognizing his creation of a new category distinct from the use of photography as mere documentation of a performance.

Skin

Irritation - There Is a Criminal Touch to Art

For Irritation - There Is a Criminal Touch to Art Ulay stole Hitler's favorite painting, Carl Spitzeg's The Poor Poet (1839) from the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin and took it to the home of a migrant Turkish family, where he hung it on the wall. Spitzeg's painting depicts a poet in a dilapidated home whose stove appears to be fueled by his own manuscripts, and was considered by Ulay to be a "German identity icon", recalling that it was the only color reproduction in one of his childhood schoolbooks. By stealing this symbol of German national identity and displaying it in the home of those usually ignored by the society, Ulay declared that art used to establish or represent a national identity often overlooks or marginalizes important truths about that nation and its view of itself. It also makes a more general point about elitism and the restriction of access to art.

To complete the theft, Ulay had studied the security situation at the gallery and the ideal exit strategy for about a week before engineering the heist. After taking the painting from the wall he made it successfully out of the building with The Poor Poet in hand. He took off in his black truck with the security guards on his heels, but, fearing capture due to the uniqueness of his truck, he got out and began running in the heavy snow. Ulay took the painting to Kreuzberg, then largely a ghetto for poor immigrant communities, and the home of a Turkish migrant family. He had spoken with the family beforehand, but only told them that he wanted to enter their home for "documentary film reasons".

Before entering the home with the painting, he called the authorities from a pay phone and said he wanted the museum director to meet him at the home to pick up the painting and certify that it had not been damaged. He then went to the Turkish family's home, removed a large art print they had hanging on the wall and hung the painting on that same nail. After about an hour, the museum director arrived, confirmed that the painting had not been damaged, and Ulay was taken to jail for twenty-four hours before agreeing to pay a fine and being released. The entire event was filmed by Jörg Schmitt-Reitwein, who also worked with Werner Herzog as a cameraman and cinematographer.

Now Ulay's most well-known solo performance (or aktion, as he preferred to call it), this piece was intended to "bring into discussion" the treatment of the Gastarbeiter, the primarily Turkish migrant workers in Germany, and to "bring into discussion the institute's marginalization of art". As Ulay stated, "Everyone should have art in their homes". In their coverage of the event, the news media referred to the artist as a "radical leftist thief" and a "madman". Ulay suffered repercussions for years, perhaps most notably in 1977 when he and partner Marina Abramović were refused inclusion in the Documenta 6 catalogue because the director of the Neue Nationalgalerie was still upset with him.

Performance - Berlin, Germany

Relation in Space

When Ulay and Marina Abramović met in 1976, they began a twelve-year collaboration that included fourteen performances they called Relation Works, which, according to culture writer Terry Nguyễn, examined "the duality and dependence inherent in romantic relationships - in relation to gender, identity, and the natural world". The first of these, performed for the Venice Biennale in 1976 was Relation in Space, for which they ran toward each other repeatedly and at an increasing speed for one hour, fully naked, colliding with one another in the exhibition space. According to Abramović, the intention was to "have this male and female energy put together and create something we called That Self," because "it was very important to collaborate and to mix our ideas together" and to "create that kind of third energy field". Subsequent works would create similar interchanges between the two bodies, highlighting both the energy that existed between the two performers and the witnesses to their interaction.

Art critic Thomas McEvilley describes the Relation Works as "mystical-philosophical approaches to the concept of the two-in-one, the mutual dependence of opposites." Nguyễn asserts that "there was an earnest synergy to the series, a mutual devotion toward their newfound togetherness. They were learning to love, while discovering how to make art in unity." Some of these performances had violent or aggressive elements, such as Light/Dark (1977) in which they sat facing one another, repeatedly slapping one another for six minutes. However, as Ulay explained, the violence of these acts did not represent how they interacted in their personal lives and was rather "the opposite of how [they] understood, lived, and loved each other".

Performance

Imponderabilia

In this piece, also part of their Relation Works (1976-88) series, Ulay and Abramović stood naked, facing each other on either side of the doorway of the main entrance of the Galleria Communale d'Arte Moderna in Bologna, forcing gallery visitors to turn sideways and squeeze past them to gain entrance. Visitors were thus forced to make a choice of which artist, male or female, to face as they brushed past, to interrupt the intimacy of the eye contact between the couple, and to come into physical contact with the artists' bodies. A hidden camera filmed each person's entry. Once inside, gallery-goers were confronted with the wall text "Imponderable. Such imponderable human factors as one's aesthetic sensitivity / the overriding importance of imponderables in determining human conduct." The performance was intended to last for three hours, but it generated a great deal of controversy and the gallery authorities put a stop to it after just ninety minutes.

Regarding the intention and concepts behind the work, Abramović explained that it "says something about the emotions of the public [and the] integration of the artists in the public" because "if there were no artists, there would be no museums, so we are living doors". In this way the two performers sought to force gallery-goers into a situation wherein they had no choice but to acknowledge the presence of the artists in the gallery space, and to reconsider their own role as the audience. As Ulay put it, they wanted to explore and "play on" the psychology of the audience. "In a flash of a second you have to make a decision and you make your decision before you figure out why," he said.

Imponderabilia, like many of the couple's other Relation Works, has become an internationally famous work, now central to the history of Performance Art. Ulay later found it "fascinating [...] that millions of people know about [the works] without ever having been there, without ever having seen them," adding "that means that what we did has travelled verbally from one generation to another and [...] we managed with our work, as shamans sometimes do, to once again stimulate the oral tradition."

Performance - Galleria Communale d'Arte Moderna, Bologna, Italy

The Lovers

In 1980, Ulay's partner in life and art, Marina Abramović, had a vision of an epic performance work in a dream. The work would involve herself and Ulay walking toward each other from opposite ends of the Great Wall of China over the course of months and holding a wedding when they met at a central point. As arts writer David Bramwell explains, "They saw The Lovers as an odyssey and a performance in which they alone would be both players and audience." They announced their plans for the work in 1983, and began preparing immediately, stocking ups on dried seaweed, tofu, and other provisions.

However, Ulay and Abramović were not prepared for the bureaucratic difficulties with which the Chinese government would present them. The government struggled to understand the purpose of the walk, failed to comprehend how it qualified as "art", and saw it as a highly dangerous undertaking that would require a large team of support staff to function properly. The couple found their requests for permissions and visas constantly denied, until 1986, when they were told they could do it the following year. They immediately went to China to begin to familiarize themselves with the landscape they would traverse. However, at the last minute, the Chinese government further postponed the performance. As Ulay remarked at the time, "I have been living with the wall in my thoughts for five years. Already I feel I have walked it 10 times. Already it is worn, it is polished."

Eventually, after agreeing to participate in a film for Chinese Central Television about their "study" of The Great Wall, the artists were granted permission to undertake their walk, beginning on March 30, 1988. By this time, however, their personal and professional relationship had grown extremely strained, due to infidelity on both sides and differing views on the correct path forward for their art. In the end, they went ahead with The Lovers, but instead of the walk leading to a wedding, it led to what might now be argued as the most famous breakup in art history. Ulay began from the Gobi Desert, and Abramović from the Yellow Sea. Each night, after walking along the wall, they would each have to walk up to two kilometers further to reach the village or campsite at which they were to sleep.

Much like earlier art/life projects the couple undertook, such as living with the Indigenous peoples of Australia, The Lovers proved to be a fascinating ethnographic journey for the two artists. Ulay spent much of his journey in the desert, coming across locals with working donkeys and camels. Both Ulay and Abramović also came across a number of families living in caves carved into the wall itself. After ninety days of walking an average of twenty km per day, the pair encountered one another at the center of a stone bridge in Shenmu, Shaanxi province. They embraced as they said a heartfelt farewell to one another, with Ulay telling Abramović that he wished he could continue to walk with her "forever". The notoriety and canonical importance of The Lovers attests to the magnitude of Ulay and Abramović's personal and working relationship and the influence of their collaboration on the contemporary history of Performance Art.

Performance - China

Performing Light

At the age of seventy-six, when his body had become depleted and weakened by old age and lymphatic cancer, Ulay performed Performing Light at the Richard Saltoun Gallery in London. For this work, he darkened the room entirely, lay in a nearly fetal position on a sheet of photo-sensitive paper, and had the audience members stretch out their arms above him as his assistant exposed the image with a flash of light, capturing in black and white the silhouette of his body and the outstretched hands surrounding him. The photograph was then installed on the wall in the exhibition space alongside much older photographic self-portraits by Ulay, emphasizing the change in his physical appearance over the decades. He explained that "I'm a body artist you see, so I don't like getting sick." Other works he created in this later period of his career that involved his own body and the bodies of audience members in the creation of life-sized photograms include Ulay Life-Sized (2000), Family at 4 O'Clock (2007), and 5 Greek Men (2008).

This later work by the artist serves as an ideal example of how his work functions as "performative photography" (a term coined by curator RoseLee Goldberg). Rather than a mere photographic documentation of a performance, the production of the photograph is an irreproducible and unique action, blurring the distinction between the live and the document.

While performative photography was more broadly popularized by American photographer Cindy Sherman in her series Untitled Film Stills (1977-80), Ulay was the true pioneer of the genre with his introspective performative Polaroid work in the early 1970s. As he explained, "The union of performance and photography was really a unique event in the history of photography and in the history of performance." By the end of his career, he had also added a participatory element to his performative photography works, involving the audience in the image creation and reflecting his interest in the live moment and tension between bodies in a space.

Performative photograph - Richard Saltoun Gallery, London, England

Biography of Ulay

Youth and Education

Frank Uwe Laysiepen, later to take the professional name Ulay, was born in a bomb shelter during an air raid on the steel-manufacturing town of Solingen, Germany, two years before the end of WWII. He was the only child of his mother Hildegard and father Wilhelm. Wilhelm had been forced to fight in both the first and second world wars, and as a child Ulay never met any other relatives as they had all been killed in these conflicts. The lived experience of the wars and the atrocities that took place were not discussed in Ulay's family while he was growing up, a fact that would cause him a great deal of distress later in life. He once stated "I was born into what you could call a 'social refrigerator.' I had to educate myself."

When Ulay was fourteen his father gave him his first camera. As his father liked to work in the garden and would have his son plant seeds for flowers and trees, Ulay's earliest photographs were of these plants. In the same year his father gave him this camera Wilhelm died, which caused Ulay's mother Hildegard to turn "in on herself". Ulay later remarked that for all intents and purposes he considered himself "an orphan" beyond the point of his father's death.

Ulay left home to study engineering in the early 1960s, but deviated from this path after a 1968 trip to Amsterdam during which he met an anarchist group of performers called Provos. He began photographing the group's actions and performances and signed up for the Art Academy in Cologne in 1969.

At the Academy, Ulay wanted to study photography, but as no such faculty existed he "ended up" in painting. He was already a technically advanced photographer, and as a result was often called upon to teach these skills to some of his fellow students. He recalled that, "after a year and a half, my professor called me in, offered me a bowl of goulash soup and some Unterberg (a heavy German digestive drink), and said: 'I would suggest that you leave the Academy before it spoils you. The Art School community can ruin your character, just go and do your own work.' He also told me something I now believe deeply: you cannot learn art in school. You can learn about art, but not to produce art. I was thrown out of school with the best intentions!"

Early Career

Now finding himself "in the streets" with a newfound resolve to be an artist, Ulay began collaborating with German visual artist Jürgen Klauke. During this time he became politically involved with social issues affecting people on the margins of society, or as he put it, "transvestites, homeless people, misfits". He recalled, "I felt I could find my reason for being an artist in that world." At this point, however, he also found himself in a crisis of identity and troubled by his "Germanness". Seeking to address this, in the early 1970s he packed up his belongings and left Germany to settle permanently in Amsterdam.

Ulay worked as a consultant for Polaroid for the next five years, enjoying unlimited access to equipment and film. He used his own practice to explore questions of identity, shooting himself and the "misfit" population with whom he had grown close, at times dressing as a woman, or presenting himself with a mental disability. He said, "In the first phase of my art making, my attempts were the works of a loner. I used a Polaroid camera as my witness: these were intimate performances. There was just the camera and myself."

The result of Ulay's early introspective photographic work (dealing mainly with gender) was a series of autobiographical collages titled Renais sense (1974). In 1975, Ulay held his first public exhibition at De Appel Foundation in Amsterdam (a contemporary art institution focusing on performance, which he helped to found that same year). Also in 1975, he began doing public performances, although he preferred the term aktion to "performance". This period of solo public aktions included his now notorious theft of Carl Spitzeg's The Poor Poet from the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin in 1976. He called this aktion Irritation - There is a Criminal Touch to Art.

Ulay had accompanied his new partner, Serbian Performance Artist Marina Abramović to Berlin for a series of performances, recording and taking photographs of her work, but was struck when he saw the painting displayed in the Neue Nationalgalerie. Spitzeg's work was a major symbol of German national identity and the favorite painting of Adolf Hitler, and Ulay later said that he stole it "to deal with my German-ness. I wanted to irritate it, and I did it best by stealing Germany's favorite painting". Ulay removed the painting from the wall of the museum and took it to the home of a Turkish migrant family, which he saw as making "a point about the difference between their living conditions and the safety of the art world". He then telephoned the museum director to come and collect the work, certifying that it had not been damaged.

Ulay was arrested and fined at the conclusion of this aktion and convicted and sentenced to either serve 36 days in prison or pay a fine of 3,600 deutschmark. He had began an itinerant lifestyle with Abramović by this point and evaded paying until he was detained in Munich after travelling from Amsterdam to Agadir (Morocco) a year later. Ulay paid the fine, with help from friends, but had achieved a particular notoriety in Germany through the tabloid scandal around the theft, which would present later problems when attempting to show both his work as a solo artist and his collaborative practice with Abramović in the country.

Mature Period

Ulay had met Marina Abramović in Amsterdam in 1976 before his theft of The Poor Poet, and the two had begun a romantic relationship almost immediately. Besides sharing, as art critic Thomas McEvilley notes, "remarkable similarities of physiognomy, personal style, and life-purpose", the two artists found that they shared the birthday of November 30th (though Ulay was three years older). Arts writer David Bramwell explains that, from the moment they laid eyes on each other, they were inseparable, as "Ulay found Abramović 'witchy' and otherworldly" and "she found him wild and exciting". The couple began performing and living an intense and sexually charged nomadic lifestyle together, referring to themselves as a "two-headed body," "That Self," "the third," "glue," and "the Other".

As Ulay later remarked about his partnership with Abramović, "We were a couple, male and female, and the urgency for us had an ideological basis. The idea was unification between male and female, symbolically becoming a hermaphrodite [...] We used to feel as if we were three: one woman and one man together generating something we called the third." For the next twelve years, their collaborative performances, which focused on the use of their bodies and the creation of opportunities for viewer discomfort, as well as the critical analysis of the concepts of the Ego and artistic identity, took center stage in their lives, and to this day, their collaborative works and personal relationship continue to dominate their narratives as individual artists and cultural figures.

Shortly after Ulay conducted his aktion in Berlin, the two artists embarked on an itinerant lifestyle together, moving from place to place across Europe and living with their dog Alba, in a corrugated iron Citroën van. They wrote a one-line manifesto, titled "Art Vital", which stated, "No fixed living place, permanent movement, direct contact, local relation, self-selection, passing limitations, taking risks, mobile energy." Ulay explained that this was "not a hippie idea [nor] a nomad idea, it has to do with the intensity achieved by permanent motion." Together, they performed at the 1976 Venice Biennale and the 1977, 1982, and 1988 editions of the Documenta quinquennial in Kassel, Germany. Some of these appearances were additionally complicated by the fall-out from Irritation - There is a Criminal Touch to Art, but their joint practice was rapidly recognized as a significant intervention in the rapidly developing discipline of Performance Art.

In 1980, Ulay and Abramović had the idea for an epic performance work titled The Lovers, which would consist of a walk from opposite ends of the Great Wall of China toward each other, culminating in a wedding at the point of their meeting. It took them eight years to secure approval from the Chinese government, and in that time the couple's relationship changed significantly. Several factors contributed to this shift, including infidelities and Ulay's inability to maintain the same intensity of endurance as Abramović in their collaborative performances, although the major dividing issue was that Abramović sought higher levels of acclaim and prestige, while Ulay was resistant to what he saw as the growing commercialization of their work.

The Lovers took place in 1988, but instead of the three-month, 2500 km walk terminating in a marriage, it ended with a break-up of their collaboration and romantic partnership at the point on the wall where they met. Ulay later said of their split, "For her, it was very difficult to go on alone. For me, it was actually unthinkable to go on alone. So it was actually heartbreaking for both of us." After the performance, each returned separately to Amsterdam, after which they would not see each other again in-person for twenty-two years. Ulay had begun a relationship with his Chinese interpreter Ding Xiao Song during the walk, who was pregnant at the culmination of The Lovers. Ulay would live together with Song and their daughter Luna Rey Laysiepen for the next 17 years.

Late Period

After parting ways with Abramović, Ulay maintained primary residences in both Amsterdam and Ljubljana (Slovenia). After taking a break from art making for a few years, he returned to photography and performance work. His performances increasingly involved audience participation, and once again began to deal more directly with social and political issues, such as the expansion of the European Union, women's rights in Morocco, elephants' rights in Sri Lanka, and worldwide access to clean drinking water. As he put it, "art without ethics is cosmetics".

From 1998-2004 Ulay worked as a professor of new media at the Hochschule für Gestaltung, Karslruhe in Germany. His seminars involved taking students to the Black Forest for a week, during which they had to survive in the wilderness, similar to an Australian Aboriginal walkabout.

In 2010 at her MoMA retrospective, Abramović performed The Artist is Present, in which she sat across from an empty chair that audience members could sit in and share a moment of silence with the artist. This performance shared many elements with an earlier work she had developed with Ulay, Nightsea Crossing (1981-87). Ulay attended unbeknownst to Abramović, and when he took the seat and Abramović opened her eyes and saw him, she reacted emotionally, crying, and breaking her "no contact" rule to reach across the table between them to take his hand. Video documentation of this moment would circulate widely across print, broadcast, and social media, cementing the growing recognition and art world profile of Abramović (and, to a lesser extent, Ulay). It was later reported that Ulay had to be persuaded to attend this performance by his family and gallery, who were insistent that his contribution to their shared work should be recognized and present in the record of the exhibition.

Despite their moment of reconnection, 5 years later Ulay took Abramović to court claiming that she had failed to pay him sufficient royalties for sales of their joint works. In September 2016, a Dutch court ruled in Ulay's favor. In 2017, the pair reported that they were once again on good terms. Said Ulay, "Everything naughty, nasty disagreements or whatever from the past, we dropped. We became good friends again. That's a beautiful story actually." Likewise, Abramović asserted that "this really beautiful work that we left behind [...] is what matters," adding that "Looking back, this relationship was extremely important for the history of performance art".

In addition to his daughter with Deng Xiao Song (who was named Luna after he delivered her himself by moonlight), he also had a son from his earliest marriage, which had lasted for approximately three years in the mid-1960s, and another son from a relationship he had with artist Paula Françoise-Piso in Amsterdam from 1971-75. He later said of these two early relationships, "I left the mothers of my children twice because I had so much work to do on myself and I gave priority to my own development and existence. So, I left, I ran away." In 2012, Ulay married Slovenian graphic designer Lena Pislak.

In 2011, Ulay was diagnosed with lymphatic cancer. His battle with the disease was documented in Slovenian director Damjan Kozole's 2013 documentary film Project Cancer: Ulay's Journal from November to November. He went into remission in 2014, the same year as he established The Ulay Foundation in the Netherlands to preserve and promote his artistic legacy, but suffered a recurrence a few years later. He passed away at the University Rehabilitation Institute in Ljubjana on March 2, 2020, at the age of 76. His New York gallerist, Mitra Korasheh, wrote that he "was incomparable. The most influential and generous artist I have ever known, the most gentle, selfless, ethical, elegant, witty, the most incredible human."

The Legacy of Ulay

Ulay is best known and remembered for his collaborative, body-centric performance work with Marina Abramović, which was massively influential on the development of Performance Art as a defined medium in its own right and as a direct inspiration for innumerable artists, including Chris Burden, Coco Fusco, Nao Bustamente, Guillermo Gomez-Peña, and Annie Sprinkle. However, Ulay's solo work in performance and photography was also pioneering. He was the first recognized artist to used body modification (tattooing and piercing) and plastic surgery as part of his Performance Art, prefiguring the later work of other artists like French Performance artist Orlan, who underwent a series of plastic surgeries to change the appearance of her face or Japanese artist Mao Sugiyama who had his genitals and nipples surgically removed in order to promote asexual rights.

Ulay's pioneering use of photography as performance (rather than to simply document performance) paved the way for artists like Cindy Sherman to engage in "performative photography" (a term coined by curator RoseLee Goldberg to retroactively describe Ulay's early explorations of self through Polaroid photography). As gallerist Richard Saltoun writes, "Ulay was the freest of spirits - a pioneer and provocateur with a radically and historically unique oeuvre, operating at the intersection of photography and the conceptually-oriented approaches of performance and body art."

Ulay's legacy is maintained by his family and gallerists, as well as the foundation he established in the later period of his life. There has been a greater interest in his contribution to his shared works with Abramović, particularly following the successful civil case in 2016. As Abramović's public profile has grown and been the subject of increasing controversy (both politically and in relation to her use of volunteer performers and connections to celebrities and wealthy elites), several academics, historians, and gallerists have published works which seek to reassert his importance and centrality to these now commercially and canonically valuable works.

Influences and Connections

-

![Marina Abramović]() Marina Abramović

Marina Abramović - Jürgen Klauke

-

![Performance Art]() Performance Art

Performance Art -

![Collage]() Collage

Collage -

![Conceptual Art]() Conceptual Art

Conceptual Art -

![Fluxus]() Fluxus

Fluxus - Photography

-

![Ana Mendieta]() Ana Mendieta

Ana Mendieta -

![Chris Burden]() Chris Burden

Chris Burden ![Stelarc]() Stelarc

Stelarc- Karl Wratschko

- Ron Athey

-

![Marina Abramović]() Marina Abramović

Marina Abramović - Jürgen Klauke

- Christian Lund

- Jaša

-

![Performance Art]() Performance Art

Performance Art -

![Collage]() Collage

Collage -

![Conceptual Art]() Conceptual Art

Conceptual Art - Performance Photography

Useful Resources on Ulay

- Ulay & Marina Abramovic: Modus VivendiBy Thomas McEvilley

- Art, Love, Friendship: Marina Abramovic and Ulay, Together & ApartOur PickBy Thomas McEvilley

- The Art of Living: An Oral History of Performance ArtBy Dominic Johnson

- Ulay: What Is This Thing Called Polaroid?By Frits Gierstberg and Katrin Pietsch

- Ulay: Life-SizedOur PickBy Matthias Ulrich and Max Holheim

- Ulay - Luxemburger PortraitsBy Lucien Kayser and Maria Ruiter

- Visionaries and the Art of Performance: Blake, Allen Ginsberg, John Latham, Ulay and Other MastersBy Orietta Benocci Adam