Summary of Paul Nash

Paul Nash painted deeply romantic and lyrical landscapes subtly re-envisioned through the shards of modernism and the horrors of war. He was a prolific and hugely talented artist, a writer, a photographer, a fine book illustrator and designer of stage scenery, fabrics, and posters, as well as most famously, a painter. Although Nash embraced and encompassed many of the major twentieth century art movements, including Surrealism and abstraction, his intense love for nature and surrounding landscape always remained the primary subject of his work. Indeed, even in his duties as official war artist - during both great wars - while documenting the broken debris of battlefields and feeling traumatized by the destruction that he saw, he still managed to make everything that he depicted appear somehow enchanted; gnarled and broken trees resemble ancient standing stones and sunlight or moonbeams usually peak through. As such Nash gives his viewers a magical gift: the insight that even from death springs rebirth, and furthermore, that the imagination always transforms, even the most horrific of scenes.

Accomplishments

- In his deep attachment to the countryside, his persistent understated romance, and his interest in the perpetual cycle of time, there is something quintessentially English about the work of Paul Nash. He is connected to a lineage of the English Romantic poets, and to famous landscape painters, most notably to William Blake and J.M.W. Turner. He was also influenced by the artists Samuel Palmer and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and like all of the above successfully placed English art on an international stage.

- Although he never joined any modernist movements, Nash worked with and had links to some of the most important British artists of the first half of the twentieth century. In the Summer of 1914, before enlisting as a soldier he worked with Roger Fry in the Omega Workshops. In 1933 he established the Unit One group with Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth. Later in the 1930s, he became close with Eileen Agar and started to write about "seaside surrealism".

- Nash successfully exposed the "bitter truth" of war through a series of muddy trench pictures from WWI; he created invaluable documentary material of changes to the landscape experienced following trench warfare. During WWII Nash produced a series called "aerial creatures", showing German planes crashed in various landscapes. Throughout both wars he was officially employed by the government but remained an ambiguous and highly political individual within the system. Nash once superimposed Hitler's head on one of his wreaked aircraft pictures and wanted these dropped as postcards all over the Third Reich.

- In later work, Nash was heavily influenced by Surrealism, and especially by the 1928 Giorgio de Chirico exhibition that he had seen in London. Unlike other Surrealists, he concentrated on mysterious aspects of landscapes rather than the placement of uncanny objects. He was very interested in the impact of man on nature. He explored this relationship in an incredible imaginative feat, through a series of late paintings called "aerial flowers" - thus a combination of complex human invention and the simple beauty of nature - a potential precursor to Salvador Dalí's; iconic image of the Meditative Rose (1958).

Important Art by Paul Nash

We are making a new world

Having returned from his service in WWI with many watercolors and pastel sketches depicting the landscapes he had seen, this is one of Nash's first oil paintings, based on the drawing Sunrise, Inverness Copse (1918). Both his drawing and painting that followed depict the war-torn Western Front, where the trees have been burned or beaten away and the earth has become scarred and undulated by shell holes. There are no people, but the tree stumps have an eerie human presence. Indeed, the trees are either personified or they stand as gravestones for the men no longer standing there themselves.

Despite a tone of pessimism and a scene wrought with destruction, the sun beats down and continues to illuminate this land. This light works on two levels; it shows a glimmer of hope that Nash cannot let go of, but also introduces a tone of mockery with regards the purpose and intent of war. The latter rings particularly true when considered in respect to the title of the work - We are making a new world - which acts both as a parody of the naive ambitions of war and as a description of how the landscape has been subjected to such destruction that it is almost unrecognisable. Former curator at The Imperial War Museum, Roger Tolson, affirms "In Nash's bitter vision the sun will continue to rise each and every day to expose the desecration and to repeat judgment on the perpetrators. This new world is unwanted, unlovable but inescapable."

This work is generally considered to be one of the most memorable images of the First World War and has been compared to Picasso's Guernica (1937) - the Spanish Master's legendary response to the bombing of the eponymous town. Nash poignantly subverts the usually peaceful and picturesque English landscape tradition and introduces a new element of horror. As such, the painting well embodies his comments of the previous year with respect to his role as a war artist: "I am a messenger who will bring back word from men fighting to those who want the war to last forever." This message, he claimed, would reveal the "bitter truth" of war.

Oil on canvas - Imperial War Museums

The Menin Road

The proposed title for this work was A Flanders Battlefield. It had been commissioned by the Ministry of Information in 1918, on the theme of heroism and sacrifice, and was intended to be shown in a Hall of Remembrance dedicated to "fighting subjects, home subjects and the war at sea and in the air". The Hall, however, was never built, and the painting is far from a celebratory depiction of war. It shows a flooded trench, ground split apart by shells, stumps of trees, and other broken debris including wire, metal, and concrete. In the background, smoke suggests that the destruction is ongoing. Nash himself suggested the following caption for the painting: "The picture shows a tract of country near Gheluvelt village in the sinister district of 'Tower Hamlets', perhaps the most dreaded and disastrous locality of any area in any of the theatres of War."

This is Ypres in Belgium, an area that was entirely destroyed during the Battle of the Menin Road Ridge. The extent of the devastation is further emphasised by two soldiers at the centre of the picture who attempt to follow the road that no longer exists. Every inch of the picture is filled with some form of rubble, and none of the small criss-crossing paths reach the horizon. The resulting impression is that there is no escape or relief from this horror. As art historian Paul Gough notes, the viewer seeks a way through the obstacles, but "the horizon is unreachable, locked in some unimaginable future". Even the beams of sunlight that pierce through the scene have some resemblance to the barrels of guns. Man has utterly betrayed nature in this scene.

The color scheme of the painting has been said to derive from Flemish tapestries, whilst the artist and critic Wyndham Lewis's description: "an epic of mud" also calls to mind images of historic battle tapestries. Indeed, Gough praised Nash for capturing the disfigurement of the landscape and agreed with the artist that this was one of his finest works. There is a trace of Vorticist influence in these early war paintings by Nash. This was the English movement headed by Wyndham Lewis that aimed to express the dynamism of modernism through art and poetry. Nash has most in common with C.R.W. Nevinson - with both adopting an angular style for the battlefield - but this influence did not really become particularly decisive for him and did not impact his work anywhere near as much as his love for English landscape traditions from the nineteenth century.

Oil on canvas - Imperial War Museums

Equivalents for the Megaliths

In 1933, Nash visited the village of Avebury, in Wiltshire, southwest England. He became "excited and fascinated" by the Neolithic monuments and standing stones that he found there, in which he saw at once "magic" and "sinister beauty". He painted the landscape several times in different styles, and in this case he introduces abstraction to further highlight the sense of mystery encountered at the site. In a letter to the then Director of the Tate Gallery (from 1951), Nash's widow wrote that Equivalents for the Megaliths had "a beautiful design, and is, in my opinion, the most important of the Megalith series of paintings".

In Equivalents for the Megaliths, Nash re-imagines the historic standing stones as abstract forms typical of contemporary sculpture. In a statement on the painting, written in 1937, the artist speaks of the monuments' dual appeal: their impressive age value and their capacity to represent bygone eras; and their formal, geometric appeal ("lines masses and planes, directions, and volume"). The artist felt that both the history and geometry of these stones lent them a mystical presence.

Indeed, Barbara Hepworth's Two Forms With Sphere (1934) could have been an influence on this painting, as may have been the nineteenth century artist, Thomas Guest's Finds from a Round Barrow at Winterslow, Wiltshire (1814), a fellow artist deeply interested in archeology and the ancient remains of past English civilizations. Some critics have also noted the painting's similarity to his brother John Nash's The Cornfield (1918) in the geometric and ordered treatment of landscape. This is perhaps in deliberate contrast to Nash's previous war paintings, which are characterized by chaos, ruin, and disarray, an attempt in pictures to re-establish harmony and balance.

At this point Paul Nash had fully recovered from his breakdown in the early 1920s that had come about as a result of "war strain". During the decade that followed he built a friendship and artistic relationship with fellow English modernist, Ben Nicholson. As result, in 1933, Nash formed a group called Unit One that included Nicholson and his wife, Hepworth. Equivalents for the Megaliths was exhibited during the two years that Nash was affiliated with this group. He shares his subdued, understated, and pastel palette with Nicholson and the interest in organic geometrical forms with Hepworth. Furthermore, the two great painters both had a love for landscape but whereas Nash always remained more lyrical, Nicholson engaged further with abstraction.

Oil on canvas - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

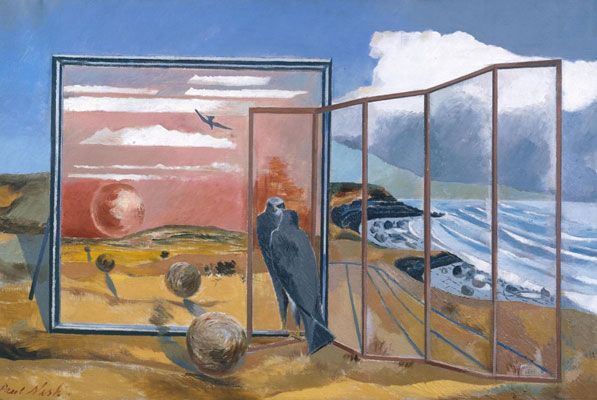

Landscape from a dream

This painting is widely considered to stand as the culmination of Nash's personal response to Surrealism, in which he had taken an interest since the 1920s. The work was completed shortly after Nash visited the International Surrealist Exhibition of 1938 and it is inspired by the Surrealists' fascination with Freud as well as by their principle theories surrounding the power of dreams. At the time, Nash had also recently met and become a good friend of the Surrealist artist, Eileen Agar who like Nash spent a great deal of time walking the coast and finding inspiration there. Along with connections to Agar, the dominant cloud filled sky and central objects placed in a mystical landscape bear strong resemblance to the work of René Magritte. Magritte was a long-standing influence for Nash and one that he returned to towards the end of his career when painting his "aerial flower" series.

The painting shows a hawk contemplating itself in a mirror, in which there is also a landscape and several spheres. The action is set within another landscape - the Dorset coast - though it is contained between screens. The mixture of the unusual activity at the centre of the painting combined with the recognisable surroundings outside it, results in an overall impression that is both unsettling and intriguing. This combination of familiar and unexpected has much in common with the nature of dreams. Nash later explained the symbolism of each of the elements in the painting: the hawk represents the material world and the spheres, the soul.

The artist and historian Roland Penrose praised Landscape from a dream, drawing a similarity between the bird looking at itself in the mirror and the viewer contemplating the painting. He wrote that just as the bird "watches itself in a glass, waiting for the image to move so as to know which is really alive, itself or the image", Nash's paintings "[assert] their independent life". This idea of movement becomes more complex in view of the fact that Nash painted the bird from an Egyptian carving. Thus the "real" hawk is immobile and the flying hawk in the mirror is an illusion. The carving from which the hawk was painted now adorns the artist's grave.

Oil on canvas - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Totes Meer

Totes Meer (Dead Sea) was painted during the Second World War. Nash wanted to title the work using the original German as he intended the picture to be seen by the German people and to reveal the fall and failure of their military attempts to dominate Europe. As such, the work can in a way be viewed as a subtle, patriotic statement in support of the British war effort. It was submitted to the War Artists' Advisory Committee in 1941 - for whom Nash worked intermittently throughout WWII - and shows a "dead sea" of destroyed German planes.

Nash based this painting on sketches and photographs that he had made and taken at the Metal and Produce Recovery Unit near his Oxford home. He then collaged his collection of images together to create a fragmented sea of battered remnants. He particularly wanted to represent German planes (as opposed to the British ones occupying most of the recovery unit) so as to illustrate the fate of the "hundreds and hundreds of flying creatures which invaded these shores". His unrealised vision was to distribute a postcard of this image throughout Germany as propaganda. Somewhat grimly, he even creating a version of the painting with Hitler's head collaged on to the damaged aircraft, for this purpose. A year later, he extended this interest and made the work Follow the Fuhrer (1942), whereby a squadron of German aircraft fly through the sky accompanied by a huge flying shark. Here Nash successfully uses techniques of Surrealist collage to convey the colossal and brutalising force of Adolf Hitler.

Paradoxically, the inclusion of the moon in the background of Totes Meer adds "incongruous beauty" to the painting and in typical Nash style, suggests the unwavering power of nature, in spite of man's atrocities. The landscape beyond the broken sea of planes suggests that salvation remains a possibility and that the destruction, though horrific, is not total. Kenneth Clark called Totes Meer "the best war picture so far", and this is an opinion still held by many. Of this painting and The Battle of Britain (1944), Clark further commented on Nash, "you have discovered a new form of allegorical painting. It is impossible to paint great events without allegory ... and you have discovered a way of making the symbols out of the events themselves".

Oil on canvas - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Battle of Britain

The composition for Battle of Britain was inspired by a 19th-century lithograph showing a storm over Paris, which Nash's wife Margaret had shown to her husband's pupil, Richard Seddon. At first glance, the coastal landscape, brilliant blue sky, and carefully rendered cloud formations dominate this painting, which takes a view from Britain in the foreground - across the English Channel - to France in the background. However it soon becomes apparent that the scene is set in the midst of an aerial battle, the Battle of Britain, and that the landscape is under attack. Entwined with the clouds are the trailing paths of airplanes, whilst darker trails of smoke are signs of combat and of damaged, sometimes falling planes. At least one of these black smoke trails was not painted by Nash but by his student, Richard Seddon, who advised his teacher that he should add more of these destructive marks to the work.

Nash painted this work during the battle itself, explaining that it contains characteristic elements such as the winding river across the parched countryside, the cumulus clouds after a summer day, and the trails of airplanes in the sky, both those that are still flying and those that are burnt and falling. The Germain air force (Luftwaffe) can be seen advancing in formation, whilst - in a midst of vapour trails, cloud, smoke, parachutes and balloons - British RAF pilots break up these forces at the centre of the painting. The British planes rise almost from the earth itself, lending the landscape more grandeur, poetry, and dignity than is seen in Nash's earlier, more devastating paintings.

Characteristic of Nash's work at this time, the painting is not entirely true to life but takes on an imaginative and symbolic edge, which in part is demonstrated by discrepancies in scale between the action in the sky and the landscape below. Rather than render a particular, realistic battle scene, the painting speaks of large-scale, dramatic aerial conflict. Nash wrote "The painting is an attempt to give the sense of an aerial battle in operation over a wide area and thus summarises England's great aerial victory over Germany." In this sense, it could be considered a patriotic work.

Oil on canvas - Imperial War Museums

Battle of Germany

Battle of Germany was the last painting that Nash completed under his official employment for the War Artists' Advisory Committee (WAAC). The commission had stated that the committee would like a sequel to Nash's Battle of Britain (1941), a picture that would depict a flying bomb. Nash, however, was not inspired by this idea at all, writing "It has fallen through I think. I did not find any point of departure, no bomb site as it were to launch into a composition." Instead, Nash chose to paint a German city under attack from aerial bombardment. In order to do so, he was given access to reports from crews who had participated in German air raids. Despite such detailed research, there is very little evidence of this in what is essentially a predominately abstract canvas.

The composition of Battle of Germany is divided into "the suspense of the waiting city under the quiet though baleful moon" on the left, and the city under bombardment on the right. The former is characterized by stillness and quiet whereas the latter shows the "violently agitated" sky and sea. In the center, smoke and a red blaze loom over the city, whilst patches of color across the canvas suggest further blasts and spreading disruption. The group of small circles in the foreground represent parachutes, which poignantly and poetically mirror the form of the large moon. Overall, the painting is generally seen as the culmination of abstraction in the artist's work.

On seeing the painting, the Chairman of the WAAC Kenneth Clark responded with both admiration and confusion. Finding the "different planes of reality in which it is painted" - possibly the combination of abstract and figurative elements or the juxtaposition of two landscapes - difficult to understand, he nevertheless saw in the painting an innovative stride towards the future and to post-war art.

Oil on canvas - Imperial War Museums

Eclipse of the Sunflower

From 1942 onwards, Nash had been visiting his friend and fellow artist Hilda Harrison's house in Oxfordshire, nearby his childhood home. Here he observed sunflowers obscuring his view of the Wittenham Clumps during summer. A curator at the Tate Gallery refers to his interest in the "rhyming shapes" of the rounded sunflower heads, hills, moon and sun - a fascination that is reflected also by We Are Making a New World (1918) with its shafts of sunlight, and the steady moon in Totes Meer (1940-1). Eclipse of the Sunflower is one in an intended series of four paintings in which Nash wanted to use the life cycle of the sunflower to represent the sun in the sky - referring to his ambition as "exalt[ing]" the image of the sunflower. Before his death in 1946, the artist completed both this work and Solstice of the Sunflower (1945) but did not manage to paint The Sunflower Rises and The Sunflower Sets.

There are two sunflowers in Eclipse of the Sunflower, one in the bottom left, lying dead and withered, and one floating high in the position of the sun. This sunflower in the sky is healthy, but is perhaps about to be eclipsed. The head of the dying sunflower has just become detached from its stem and thus some critics suggest that the picture represents looming death and the moment that the soul leaves the body. The inky background may have been inspired by the illustrations of William Blake, with details that are reminiscent of earlier landscape paintings, for example the painterly cloud formations and waves in the bottom right corner. There is also a strong sense that the life cycle of the sunflower mirrors the waning and waxing of the moon, and thus the painting illustrates one of Nash's primary interests, that of death and rebirth and the ongoing continuum of natural forces.

Eclipse of the Sunflower is ever the more poignant image given Nash's first-hand experience of death during war and now, that it is made shortly before his own life came to an end. Although he was only 57, the artist had been diagnosed with bronchial asthma and would die of pneumonia shortly after making this work. The artist having become particularly interested in the idea of renewal through death (inspired by poetry and religious myth), was influenced particularly from James Frazer's painting The Golden Bough (1926), which describes a Midsummer ritual of rolling burning "fire wheels" down a hill to imitate the movement of the sun, and William Blake's beautiful poem "Ah! Sunflower" (1794). With the life cycles of nature on his mind, Nash wrote in his essay Aerial Flowers (published posthumously in 1947): "Personally, I feel that if death can give us [a solution], death will be good."

Oil on canvas - British Council Collection

Biography of Paul Nash

Childhood

Paul Nash was born in Kensington, London in 1889. He was the son of barrister, William Henry Nash and of navy captain's daughter, Caroline Nash. He was the eldest child, and brother to John (also to become a very accomplished and well-known artist) and Barbara. When Paul was only three years old, his family moved to the Buckinghamshire countryside in an attempt to benefit his mother's deteriorating mental health. The financial cost of his mother's treatment (which included long spells in a hospital) necessitated that the Nashes rent out their family home, during which time Paul and his father lived together in smaller accommodation whilst his siblings attended boarding school. Sadly, the family's efforts were in vain. Nash's mother did not recover and died when the artist was in his early teens.

As a child, Nash was described as "ill at ease in the world". He enjoyed escaping his strained reality through avid reading and retreating to secluded parts of the Buckinghamshire countryside. Already from a young age, Nash was very inspired by nature, and in particular, by trees. He described the trees in the garden of his family home as "Hurrying along stooping and undulating like a queue of urgent females with fantastic hats". Via such ideas he attributed an anthropomorphic quality to nature, an idea that he often returned to in his mature paintings.

Sadly, school life was also difficult for Nash. He failed to excel in any of his subjects and said that he generally felt "misery, humiliation and fear". He failed to pass the Naval Entrance Examination which led him away from his intended career (following in his grandfather's footsteps) and instead, a fellow pupil at his school encouraged him to consider a future as an artist. Initially, this was a novel idea, for Nash had come from a family for whom art appreciation, according to the Times Literary Supplement, "hadn't meant much more than pinning Paul's and John's watercolour squiggles on the walls."

Education and Early Training

In 1906, Nash began attending the Chelsea Polytechnic, now Chelsea College of Art. Two years later, he moved to the London County Council School of Photo-Engraving and Lithography, a study environment that he enjoyed and described later as 'ha[ving] an atmosphere of liveliness and work." Here, students learnt the practical skill of how to make a living producing posters, layouts, and bookplates. During this happy and productive time, Nash's landscape drawings caught the eye of painter and printmaker William Rothenstein, who championed the young artist and suggested that he enrol at the Slade School of Art.

Of his first meeting with the Slade tutor Henry Tonks, Nash wrote "It was evident he considered that neither the Slade, nor I, were likely to derive much benefit". Indeed, Nash did not do well at figure drawing and as such Tonks, unlike Rothenstein, did not appreciate Nash's talents. As a result of this conflict with a senior tutor, Nash left the Slade within a year, parting also from the influential generation of artists alongside whom he had begun to study including Stanley Spencer, Mark Gertler, David Bomberg, C. R. W. Nevinson, and Dora Carrington.

Nash returned to Buckinghamshire at this time and began a series of landscapes and tree studies, often set at night. He discovered a new natural site, the Wittenham Clumps, a wooded area near his uncle's house, and this became a subject to which he would return again and again. By the time of his return to Buckinghamshire, Nash's younger brother John had also started to paint landscapes, and the two showed their work together in the early 1910s. Nash also used this time to experiment with different painting techniques, including watercolor and more illustrative, graphic styles.

Mature Period

When WWI broke out in 1914, Nash joined the Artists' Rifles Brigade. In the same year he married Margaret Odeh, a campaigner for Women's Suffrage, but it was not long before he was sent to the front. There, Nash was "exhilarated by the sense of purpose" and made several sketches. At the hand of fate, he was sent home with injured ribs (having fallen into a trench) before seeing any action. A few days after being sent home as an invalid, the majority of his remaining unit were killed during a surprise assault and as such from this point onwards, Nash felt extremely lucky to be alive. Having made multiple sketches that impressed people upon his return home, Nash, along with his brother, John, became officially employed as war artists.

When Nash had recovered his broken ribs and returned to the front to glean images of the conflict, his experience changed entirely and he no longer felt an invigorated sense of purpose. This time round, Nash was frequently subject to shelling and heavy bombardment and started to describe the war as "unspeakable, godless, hopeless". He felt uncomfortable in his position as an official war artist, and wrote home, "I am no longer an artist... I am a messenger to those who want the war to go on for ever ... may it burn their lousy souls." In spite of this, he did his best to get as close as possible to the action so as to make "fifty drawings of muddy places", which would go on to inspire many of his future paintings.

On his return home for the second time, this time at the end of the war, Nash started to work his drawings into oils, with the first wave of notable paintings including We Are Making a New World, The Ypres Salient at Night, and The Menin Road. These three paintings were all exhibited at the "Void of War" exhibition in 1918 and established Nash as a highly significant artist in general, and more specifically, as the authority on the presentation of war-torn battlefields. Critics praised Nash's "dignified rage" and greatly admired the way he captured the unusual and eerie atmosphere of No Man's Land.

In spite of his success as an artist, Nash's physical and mental health were both badly damaged as a result of the living conditions in the trenches. In 1921, he spent a week in a hospital, mostly unconscious, going on to make a series of pictures of the. During this time - a time of recovery from trauma - Nash also explored other modes of artistic expression including theatre design, bookplates, textiles, and wood engraving, and also worked as an art teacher. Whilst acting as a tutor at the Royal College of Art, two of his notable students included Eric Ravilious and Edward Bawden.

Nash's career continued with successful exhibitions at the Leicester Galleries in 1924 and 1928. These shows demonstrated Nash turning away from landscapes and beginning to explore abstraction, often combining these two interests. In 1929, he travelled to Paris with his friend and fellow English painter Edward Burra, where the two met Max Ernst and Picasso. This trip inspired Nash to explore Surrealism as a useful language through which to highlight the mysterious and spiritual aspects that he already felt strongly within landscape. Indeed, from this point forth, Nash became a pioneer of Modernism, Abstraction, and Surrealism, founding the Unit One movement in 1933, which greatly helped to revitalise British art during the interwar period. Unit One came together with the support of his friends and contemporary fellow artists, Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, and Ben Nicholson, among others.

Late Period

Between 1934 and 1936, Nash lived in Dorset, where the sea air was thought to be good for his asthma and he worked on producing a guidebook for the area. In his article Swanage or Seaside Surrealism (1936), he described the area as having "a dream image where things are so often incongruous and slightly frightening in their relation to time or place." It was here that Nash identified most closely with Surrealism, experimenting with found objects and starting an affair with fellow (married) artist Eileen Agar, with whom he collaborated on several works. The affair was passionate and long-standing, starting in 1935 when the two artists met and only ending in 1944. All the while both figure remained married to their respective partners. When Agar ended this relationship, possibly because she had started a new love affair with Paul Éluard, Nash was reportedly devastated and moved back to London with his wife. Nash has referred to himself as a "gentle minded creature" and as such it was very difficult for him to reconcile within himself the idea of going to war. He was also an intensely curious personality and was generally attracted to strong and unusual women. Before marrying a suffragette and falling in love with the sexually liberated Agar, during his art school days, Nash was immediately drawn to and became great friends with the highly eccentric Dora Carrington.

When WWII began in 1939, Nash was considered too ill to fight but was once again appointed as an official war artist by the War Artists' Advisory Committee (WAAC). As a long-standing aircraft enthusiast, he was fortunate to be working with the Royal Air Force and Air Ministry. However, officials were generally wary of his imaginative and anthropomorphic depictions of planes, and it was only thanks to the intervention and financial support of chairman of the WAAC, who was also the renowned art historian Kenneth Clark, that he was able to continue painting. Clark's support gave Nash the artistic freedom he needed to continue making his surreal depictions of aerial conflict. His paintings became increasingly abstract, culminating in the Paul Klee -esque Battle of Germany (1944), Nash's final work for the WAAC.

Nash's WW II paintings are amongst his best known; in particular Totes Meer, Battle of Britain and the aforementioned Battle of Germany, which show war-torn landscapes and mangled machinery, yet always remain mythical or dreamlike in appearance. During periods in which he was unable to paint due to depression or asthma (for example after completing Battle of Britain), Nash produced photographic collage using motifs from previous works, and often accompanied by images of Hitler. He even personified Hitler as a (a particularly mean) flying great white shark in one of his collages made during this period. The Ministry of Information declined to use these controversial images as propaganda, despite Nash submitting a whole series called Follow the Fuehrer for this very purpose.

From 1942 onwards, Nash made regular visits to the home of artist Hilda Harrison. These trips were both creative and recuperative for the artist. The country air was thought to benefit his health, and from Harrison's home he once again had a good view of the Wittenham Clumps, the landscape that had so inspired him as a child. Following the completion of his last work for the WAAC, Battle of Germany, in 1944, Nash spent the next eighteen months in "reclusive melancholy". He died in his sleep on 11 July 1946 of heart failure - a result of his long-term asthma. He was buried in Buckinghamshire, and the Egyptian stone carving of a hawk that he had painted in Landscape from a Dream (1936-8) was placed on his grave. A memorial exhibition and concert were held for the artist at Tate in 1948 and were attended by the Queen (the wife of King George VI and mother of Elizabeth II).

The Legacy of Paul Nash

Throughout his career, Nash (quite accurately) saw himself as successor to J.M.W. Turner and to William Blake. Like these inspirational figures before him, he attempted to capture the "spirit" of the English countryside, and according to curator Jemima Montagu, "was able to develop a unique form of expression which evolved out of, and yet has come to define, an idea of the English landscape". This skill was particularly marked in his work as a war artist, a role he was instrumental in shaping. A soldier as well as an artist, Nash's paintings are strikingly honest about the devastating effects of war and particularly its impact on the landscape. For artist Alice Channer, Nash's work resonates strongly to this day. She writes, "Here we are, nearly a century later, looking out at identical and vast landscapes of industrial destruction ... Nash's war landscapes give us some idea of how we got here."

In the Tate retrospective that followed his death, Nash was celebrated for his war art, for his landscapes, and for his affiliation with Surrealism. It is the first two associations that Nash is perhaps best known, although it is important to remember that Nash also produced prints, engravings, lithographs, books, fabrics, rugs, glass, ceramics, and interiors. Tate's assistant curator Inga Fraser draws attention to the range of Nash' influences and output, stating "Nash's modernism was generous and inclusive" and goes on to cite a notebook in which the artist kept lists indicating the diverse references from which he drew. One such list reads "Cézanne, Cubism, artificial pattern, bricks, mosaics, stones, tiles, machinery, Léger, photography, hieroglyphics, block printing, cloth making, and film, natural forms... miscellaneous fireworks, sign, lighting... Woolworths."

Indeed, Nash's artistic career could be said to be full of surprising contrasts. As arts writer Marta Maretich points out, it is ironic that his most famous works, showing the horror and destruction of war, were funded by governmental organizations, the War Propaganda Bureau and the Ministry of Information, the very institutions that he struggled with ideologically as overall he did not agree with or understand war. It is perhaps for this reason that - although Nash rarely received a bad review of his work in his lifetime - Nash seems to have posed a challenge to critics. Even the highly sympathetic Chairman of the WAAC, Kenneth Clark expressed both admiration and confusion at Battle of Germany (1944) whilst the BBC correspondent, William Cook noted that "Nash's [interwar] art was saved from academic introspection by the outbreak of the Second World War". Similarly, the artist Geoff Hands contrasts Nash's "fairly conservative persona" with his interest in Surrealism, Cubism and abstraction, a comment that perhaps characterises why Nash's "official" war work is both somewhat subversive and intriguing. Ultimately we are confronted by the typical English artist paradox, that of living and working as a "subtle radical".

Influences and Connections

-

![William Blake]() William Blake

William Blake -

![J.M.W. Turner]() J.M.W. Turner

J.M.W. Turner -

![Giorgio de Chirico]() Giorgio de Chirico

Giorgio de Chirico -

![Paul Cézanne]() Paul Cézanne

Paul Cézanne - Samuel Palmer

-

![Surrealism]() Surrealism

Surrealism -

![Vorticism]() Vorticism

Vorticism -

![Cubism]() Cubism

Cubism - European modernism

- Dan Peterson

- Michael Alford

- James Hart Dyke

- Eric Ravilious

- Edward Bawden

![Graham Sutherland]() Graham Sutherland

Graham Sutherland- Eric Fitch Daglish

- War Art

- Unit One

- British modernism

Useful Resources on Paul Nash

- Paul Nash: Outline, an AutobiographyOur PickEd. by David Boyd Haycock

- Brothers in Arms: John and Paul NashBy Paul Gough

- Paul Nash (British Artists)Our PickBy David Boyd Haycock