Summary of Morris Louis

Morris Louis became one of the leading figures of Color Field painting, along with his contemporaries Kenneth Noland and Helen Frankenthaler. In his short yet prolific career, most of which he spent in Baltimore and Washington, D.C., Louis continually experimented with method and medium, manipulating large canvases in creative ways to control the flow and stain of his acrylic paints. His mature style, characterized by layered veils and rivulets of poured acrylic paint on untreated canvases, makes his paintings some of the most iconic works of Color Field Painting.

Accomplishments

- In addition to using thinned acrylic paint to stain the weave of his canvas, as colleagues like Helen Frankenthaler and Jules Olitski also did, Louis went so far as to manipulate the canvas itself, folding and bending it to shape the flow of the paint. This innovation allowed him to eliminate his own touch upon the canvas, while still giving him a way to emphasize his medium's inherent fluidity and saturated colors.

- Louis's paintings of the 1950s established a vital link between Abstract Expressionism and Color Field Painting. He rejected the gestural abstraction of action painters like Jackson Pollock and Franz Kline, while also placing more emphasis on tonal relations and free-flowing color.

- Rather than live in New York City as many of his contemporaries did, Louis based his career in his native Maryland and nearby Washington, D.C. In this way he expanded the geographical boundaries of the contemporary art world in America and brought attention to an offshoot of Color Field Painting later termed the Washington Color School.

Important Art by Morris Louis

Charred Journal: Firewritten V

Charred Journal: Firewritten V is executed in a traditional Abstract Expressionist style, and its gestural brushwork and all-over composition are influenced by Jackson Pollock's action painting. Although it measures only about two feet wide, this work manages to achieve a remarkable sense of dynamism within a relatively compact space. Its title alludes to the Nazi book burnings in which supposedly subversive literature was destroyed in the 1930s; its pale markings against a raw, dark background evoke a written language set against a threatening void. This canvas predates Louis's exposure to Helen Frankenthaler's stain paintings in 1954, after which he began his mature Color Field work.

Acrylic resin (Magna) on canvas - The Jewish Museum, New York

Breaking Hue

The Veil series is named for its thin overlapping "veils" of acrylic Magna paint. This canvas is one of Louis's earliest experimentations with applying thin, quick-drying washes of color to unprimed canvas. The title may evoke the sense of shifting color and light that we are encouraged to perceive in this painting. It is difficult to discern where one color ends and another begins, since, in an effect unique to Magna, the underlying layers are partially dissolved by the successive pours of color, creating a diffused, melting appearance. By permitting this new kind of paint to create unpredictable effects, Louis allowed chance to play a larger role in his art: the medium itself dictated the final result. This was a way of rethinking the artist's degree of control over his own work. Although Breaking Hue does not make any visual reference to the physical world, it is an object with a life of its own.

Acrylic resin (Magna) on canvas - Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA

Dalet Kaf

Dalet Kaf is an example of Louis's later Veil paintings. In order to work within the small confines of his studio, Louis would staple canvas to the walls. Here, the sheer washes of paint cascade down the surface of the canvas, with the brighter colors muted by the "veils" of black that frame the composition. With this inventive method, Louis enlisted gravity as one of his artistic tools, allowing it to aid and shape the flow of the paint. By making his process visible, Louis emphasized the medium's inherent fluidity rather than his own authority over it. The paint itself, rather than representational content or the artist's inner psyche, has become the subject of this work.

Acrylic resin (Magna) on canvas - Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Fort Worth, Texas

Point of Tranquility

Point of Tranquility is an example of Louis's series of Florals, a later phase of his Veil paintings. In a technical innovation, Louis created each Floral by rotating the canvas as he poured the paint, rather than working from a single vantage point. The layers of acrylic then ran and dried in a form suggesting a flower, with the bleeding pigment creating a muddled, denser area at its core. The centralized arrangements of the Florals indicated another step in Louis's departure from earlier Abstract Expressionist practices, which utilized "all-over" compositions. Louis's process here also raises an important question: if he created the canvas from multiple approaches, rather than a fixed point, can its audience then choose to view it from different orientations as well? In other words, does it still have a proper "top" and "bottom"?

Acrylic resin (Magna) on canvas - Hirshorn Museum and Sculpture Garden Collection, Washington DC

Delta Theta

Delta Theta is a classic work from Louis's Unfurled series, which are among the most recognizable works of his oeuvre. For this painting, Louis folded the massive, mural-sized canvas (nearly 20 feet wide) before pouring the thinned acrylic down its surface. The color is concentrated in the two lower corners of the canvas, while the large central area of Delta Theta is left untreated and bare. By restricting his composition to the corners, rather than utilizing the center (as was traditional in Western painting) or painting an undifferentiated field across the canvas (as Pollock might have done), Louis took a new approach to pictorial space and how it could or should be filled. And, as the scholar Alexander Nemerov has noted, the monumental scale of Louis's works of the early 1960s evokes an entire era of American optimism and power, both in contemporary art and on the world stage.

Acrylic resin (Magna) on canvas - The Hirshorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C

Partition

Partition is one of Louis's so-called Stripe series, all executed in the last months of his life. In these works, the artist was still interested in optical effects of color relationships; at the same time, he took the simplification of non-representational form to extremes. The Stripe canvases demonstrate Louis's increasingly stripped-down approach to composition and form. They are highly systematic and devoid of the painter's own expressive gesture, with their streams of paint running in tight parallel groupings of narrow bands of color. These late works, which emphasize the most basic geometry of all, straight lines, point the way towards the Minimalist school of the 1960s and 1970s.

Acrylic paint (Magna) on canvas - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Biography of Morris Louis

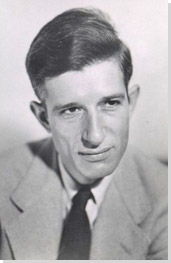

Childhood

Morris Louis Bernstein was one of four sons born into a middle-class Jewish family in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1912. His parents, Louis and Cecelia (Luckman) Bernstein, were Russian immigrants. Louis attended public schools in Baltimore and developed an early interest in art. At the age of 15, despite his parents' wishes he decided not to pursue medical studies and instead accepted a scholarship to the Maryland Institute of Fine and Applied Arts in 1927. During these early years as an artist, he was influenced by the paintings of Paul Cézanne and by visits to the Cone Collection of modern European art in Baltimore.

Early Training

After graduating in 1932, Louis worked in Baltimore for several years, becoming President of the Baltimore Artists' Association. In 1936 he moved to New York. He studied with the Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros in 1936 through 1937 and earned money as a window decorator. In 1938 he began working for the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration. He was hired by the FAP's "easel division," for which he painted images of workers and other scenes of everyday life in a style influenced by Max Beckmann and other Expressionist artists.

In 1943 Louis returned to Baltimore and continued painting in a figurative, sometimes satirical, style. He married Marcella Siegel in 1947 and moved to the suburbs of Baltimore, where he taught art classes and painted increasingly abstract works inspired by Joan Miró. In the late 1940s he began using Magna, a type of acrylic resin paint that became his preferred medium for the rest of his career. By 1950 Louis was painting in an Abstract Expressionist style heavily influenced by Jackson Pollock; his work was beginning to attain recognition among his peers and was shown at several galleries.

Mature Period

In 1952 Louis relocated to Washington, D.C., where he spent the rest of his life and career. He soon met the painter Kenneth Noland, who became his close friend and collaborator in the development of Color Field Painting, as well as the artists Franz Kline and David Smith. Through Noland, Louis met the influential critic Clement Greenberg, who became his greatest champion. Greenberg played a major part in Louis's development as a painter: in 1954 he took Louis to the Helen Frankenthaler's Manhattan studio to see her monumental work Mountains and Sea (1952). Frankenthaler's technique of staining the canvas with poured acrylic paint profoundly influenced both Louis and Noland, who returned to D.C. determined to incorporate these ideas into their own art.

Louis did not fully digest Frankenthaler's concept until approximately two years later when he began painting his first mature series, known as Veils (1957-60) because of their overlapping layers of color. (It should be noted that Louis himself rarely titled his series or his individual paintings, and with just few exceptions, the Greek or Hebrew letters and numbers assigned to his works were given posthumously by his estate.) For these works Louis poured thinned Magna paint over large unstretched and unprimed canvases, allowing the pigment to take its own course and to soak directly into the canvas.

This technique was a radical departure from the "gesture" that defined Abstract Expressionism; Louis's paint moves freely without the interference of a brush or the artist's hand. The illusion of three-dimensional depth is eliminated; his color is not a mark made on the surface but instead becomes part of the surface itself. However, Louis soon reverted to his more conventional style. When he began painting Veils again in 1957, he burned all but ten of several hundred works from the previous three years. This kind of revision and destruction was typical of his relentless experimentation and perfectionism.

Louis continued to explore the Veil concept until 1960, developing several distinct categories of work. These include the "floral" veils, so named because of their flower-like clusters of forms (e.g. Point of Tranquility, 1959-60). Louis created these various types by manipulating the canvas. Although he never wrote down his method and he strictly prohibited anyone from watching him work in his converted dining-room studio, certain assumptions can be made from close study of the paintings. His process involved homemade wooden stretchers that could be adjusted in order to tighten or loosen the canvas, so that the poured paint would run along flat areas, broad depressions, or narrow channels in its surface.

Late Years and Death

By the end of the 1950s, Louis enjoyed substantial renown. He saw his art featured in his first one-man exhibition in Washington, D.C., in 1953 and in his first New York show, a group exhibition titled "Emerging Talent" at the Samuel M. Kootz Gallery, in 1954. He then showed his work with prominent dealers in New York, including Andre Emmerich and Leo Castelli, as well as at galleries in London and Paris. Greenberg's 1960 article "Louis and Noland" in Art International helped to secure his critical reputation as a founder of Color Field Painting.

In the summer of 1960, Louis began a new series called Unfurleds. These remain his most readily identifiable, and perhaps most important, works. They are named after Louis's technique of folding the canvas before pouring the paint and then unrolling them as the paint soaked into the cloth. As large as 20 feet in width, they are his most monumental paintings. The most famous Unfurled paintings feature two rainbow patterns that flow from the edges of the massive canvases towards totally blank centers (such as Delta Theta, 1960). Although they seem like improvisations, Louis always planned and executed the works carefully, destroying any paintings that did not meet his standards.

Louis's final series of paintings, later called Stripes (1961), feature horizontal or vertical bands of fine lines running along long, narrow canvases. Unlike the free-flowing paint in previous series, the Stripes feature methodically plotted lines that do not touch one another. All gesture is eliminated, and the works are more closely related to the hard-edge paintings of Louis's contemporary Barnett Newman than to the work of Pollock. The highly simplified color combinations and regimented forms of these works prefigure the post-painterly abstraction of younger artists like Frank Stella and Ellsworth Kelly.

In 1962 Louis was diagnosed with lung cancer caused by extensive inhalation of paint vapors. He died a few months later, at the age of 49, at his home in Washington, D.C. The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York held a memorial exhibition of his art in 1963.

The Legacy of Morris Louis

Louis was extremely prolific, but his mature career was relatively short: the period between the inception of his first Veils series and his untimely death lasted just eight years. At the time of his death, only around 100 of his 600 extant works had ever been seen in public, so his influence beyond art circles was still limited. His position in the canon was bolstered by his inclusion in a 1965 show of the Washington Color School, and he continued to be hailed by Greenberg as a pioneer of Color Field Painting. Louis's importance waned during the 1970s when his champion Greenberg lost influence as a critic and the Color Field School fell out of fashion. However, his reputation has been revived since the 1980s with several major museum exhibitions, including a traveling major retrospective organized by the Museum of Modern Art in 1986. Today his work is viewed as an essential bridge between Abstract Expressionism and Color Field Painting, as well an influence on such later movements as Minimalism.

Influences and Connections