Summary of Kinetic Art

Kinetic art is a manifestation of the fascination with motion which defines a whole swathe of modern art from Impressionism onwards. In presenting works of art which moved, or which gave the impression of movement - from mobile, mechanical sculptures to Op art paintings which seemed to rotate or vibrate in front of the eyes - Kinetic artists offered us some of the most quintessential expressions of modern art's concern with presenting rather than representing living reality. Tracing its origins to the Dada and Constructivist movements of the 1910s, Kinetic art grew into a lively avant-garde after the Second World War, especially following the genre-defining group exhibition Le Mouvement, held in Paris in 1955. The group was always defined by division, however, and after thriving for around a decade, interest in the style faded; however, its ideas were carried forward by subsequent generations of artists, and it continues to provide a rich source of creative concepts and technical effects up to the present day.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- In creating paintings, sculptures, and art environments which relied on the presentation of motion for effect, the Kinetic art movement was the first to offer works of art which extended in time as well as space. This was a revolutionary gesture: not only because it introduced an entirely new dimension into the viewing experience, but because it so effectively expressed the new fascination with the interrelationship of time and space which defined modern intellectual culture since the discoveries of Einstein.

- Kinetic artists often presented works of art which relied on mechanized movement, or which otherwise explored the drive towards mechanization and scientific knowledge which characterized modern society. Different artists expressed a different stance on this process, however: those more influenced by Constructivism felt that by embracing the machine, art could integrate itself with everyday life, taking on a newly central role in the Utopian societies of the future; artists more influenced by Dada utilized mechanical processes in an anarchic, satirical spirit, to comment on the potential enslavement of humankind by science, technology, and capitalist production.

- Many Kinetic artists were interested in analogies between machines and human bodies. Rather than regarding the two entities as radically different - one being soulless and functional, the other governed by intuition and insight - they used their art to imply that humans might be little more than irrational engines of conflicting lusts and urges, like dysfunctional machines. This idea has deep roots in Dada, but is also related to the mid-century concept of cybernetics.

Overview of Kinetic Art

Declaring, "The only stable thing is movement," Jean Tinguely pioneered Kinetic Art. His sculptural machines expressed his view that all that mattered was, "To live in the present."

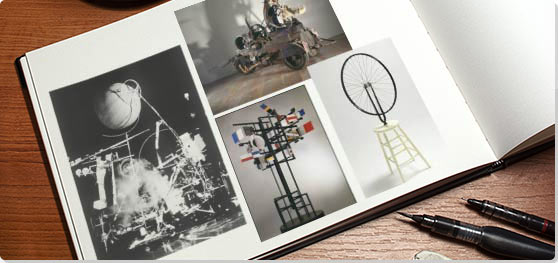

Artworks and Artists of Kinetic Art

Bicycle Wheel

Bicycle Wheel is mainly famous as the first example of what Duchamp called his "readymades": artworks which literally constituted found, generally mass-produced objects, placed in galleries or other suitably suggestive contexts and presented as works of art. In this case, however, the work contains a movable element - the bicycle wheel - and has thus also been seen as the first example of Kinetic art.

Marcel Duchamp is primarily associated with the Dada movement, and Bicycle Wheel is most significant as an expression of that movement's revolutionary attitudes to the boundaries of the art object, and its scorn for established notions of artistic form and interpretation. What is important about the work in this sense is not its incorporation of motion into sculpture but what it is not: its rejection of the artisanal modes of construction and composition central to what Duchamp derided as "retinal art". However, for Duchamp, the movement of the bicycle wheel was also essential to the work's effect. "I enjoyed looking at it," he said, "just as I enjoyed looking at the flames dancing in a fireplace. It was like having a fireplace in my studio, the movement of the wheel reminded me of the movement of flames." The first viewers of Bicycle Wheel were also invited to spin the wheel, and Duchamp went on to make more obviously proto-Kinetic works such as his Rotary Glass Plates (Precision Optics) of 1920, and his Roto-Reliefs of 1935-65.

Although Bicycle Wheel was made outside the context of the Kinetic art movement, artists of the 1950s-60s looked back on it as a precursor, evidence of a tradition of Kinetic art extending across the twentieth century. The importance subsequently assigned to Duchamp's piece also reveals the significance of Dada as a - sometimes hidden - forerunner to Kinetic art. Though in many instances, Kinetic art expressed optimism regarding the relationship between technology and humanity, for some Kinetic artists, the rise of the machine signaled the demise of a vital human spirit, or the absence of any such spirit in the first place. The somewhat abject appearance of Bicycle Wheel, and the comic pointlessness of its freewheeling motion, predict this more satirical, socially critical aspect of Kinetic art.

Bicycle wheel on wooden stool - Israel Museum, Jerusalem

Kinetic Construction (Standing Wave)

Naum Gabo's Kinetic Construction (Standing Wave) consists of a steel rod affixed to a wooden base, set in motion by an electric motor. The oscillations of the rod create the illusion of a static, curvilinear shape, a sculptural form generated entirely through movement, and arguably the first example of Kinetic art created in earnest.

The sculpture was constructed in war-torn, post-Revolutionary Moscow, where Russian artists such as Gabo were attempting to play their part in the construction of a new, Utopian society. As many of the workshops where he might have requisitioned materials were shut, Gabo used an old doorbell mechanism to power the piece. In conceptual terms, the work was meant to demonstrate the new artistic principles outlined in Gabo and his brother Antoine Pevsner's "Realistic Manifesto" (1920), the first document of modern art to speak of "kinetics" as an aspect of artistic form, announcing that "kinetic rhythms" should be "affirmed ... as the basic forms of our perception of real time". More specifically, Kinetic Construction was meant to demonstrate the principle of the "standing wave": the way that certain wave-forms move through space to create the illusion of a permanent, static presence. In both concept and context, then, this piece evokes the technological, politically radical world-view which underpinned the earliest, Constructivist-inspired works of Kinetic art.

Many Kinetic artists of the 1950s-60s revived the technological and utopian fervour of the Constructivist vanguard, making new attempts to integrate technology into art, and to establish a new, rational and scientific creative vocabulary fit for an internationalist culture. Gabo thus created a work which stands at the forefront of one part of the Kinetic art movement; at the same time, it is worth acknowleding that in its relative simplicity of form, Kinetic Construction is, as Gabo put it, more of an "explanation of the idea than a Kinetic sculpture itself".

Metal, painted wood and electrical mechanism - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Light Prop for an Electric Stage (Light Space Modulator)

The Light-Space Modulator created by Hungarian artist László Moholy-Nagy between 1922 and 1930 is an early example of the complex, mechanically-powered Kinetic art that would become more common after the Second World War. The original version displayed in 1930 consisted of a large circular base supporting various interlocking, moving components: several metal rectangles designed to jerk around in irregular fashion; perforated metal discs which released a small black ball; and a glass spiral which rotated to create the illusion of a conical form. Central to the piece's effect were 130 integrated electric light bulbs, which shone through the construction to produce mesmeric interplays of light and shadow on the surrounding surfaces. The work was first shown as part of an exhibition by the Deutscher Werkbund ("German Association of Craftsmen") in Paris; the same year, Moholy-Nagy created a film based on the sculpture, Light Play Black-White-Grey, and used the word "kinetic" for the first time to describe his own practice.

Born in Hungary to a Jewish family, in 1920 Moholy-Nagy emigrated to Germany, and by 1923 was teaching at the Bauhaus, then the most significant outpost of Constructivist principles in Northern Europe. Moholy-Nagy was partly responsible for establishing the technological, rationalist, politically radical approach to art associated with the school; working across a range of applied artforms, he focused on the integration of scientific principles into creative design, and the establishment of new compositional vocabularies for art. The Light-Space Modulator exemplifies these ideas, many of which were expressed in his "Manifesto on the System of Dynamico-Constructivist Forms", co-authored with Alfred Kemeny in 1922: "[w]e must put in the place of the static principle of classical art the dynamic principle of universal life. Stated practically: instead of static material construction [...] dynamic construction [...] must be evolved, in which the material is employed as the carrier of its forces."

Though influenced by Naum Gabo's kinetic constructions - and sketches for kinetic constructions - of the early 1920s, Light-Space Modulator represents a new level of conceptual and technical sophistication within Kinetic art. In this sense, and in terms of the date and location of its creation, it is an important transitional work, standing between the first pioneering efforts of artists such as Gabo and the ever-more complex mechanical constructions of post-1945 Kinetic artists in Western Europe and North America.

Steel, aluminum, glass, plexiglass, and colored lightbulbs - The Busch-Reisinger Museum, Harvard University

Arc of Petals

Arc of Petals is one of many examples of the free-standing or hanging "mobiles" - so christened by Marcel Duchamp - for which the American sculptor Alexander Calder became famous. Looking somewhat like an inverted, suspended tree, the piece comprises a central spine of iron wire with various petal or leaf-like appendages budding off from it; these pieces are largest and most solid-seeming at the top, smallest and most tentative-seeming at the base. The movement of the piece in the breeze is intended to play with the readers' associations of heaviness and lightness, providing a counterintuitive, irregular pattern of motion. With works such as Arc of Petals, Calder defined an important and unique sub-genre of Kinetic aesthetics, one that was concerned with the movement and dynamism of nature rather than of the mechanized, urbanized world.

Calder came from a family of sculptors and painters, and before training as an artist took a degree in mechanical engineering, learning various technical processes which he would later put to use in his Kinetic art. In the late 1920s he moved briefly to Paris, where he befriended many of the prominent modern artists of the day; his construction of mobiles as art-objects commenced at the start of the following decade. Whereas early works in this medium rely on motorized or hand-cranked mechanisms to create pre-determined patterns of movements, by the time Arc of Petals was made, Calder was generally producing mobiles set in motion by passing air currents. Initially he used materials such as glass or pottery to create these pieces, but later works such Arc of Petals were constructed from pieces of hand-shaped aluminum, painted in solid reds, yellows, blues, blacks, and whites. In this case, we can see the influence of his painter friends Joan Miró and Jean Arp in the biomorphic forms of the leaves, while a single aluminum petal left unpainted reminds the viewer of the weight and roughness of the compositional material.

Constructed with artisanal care and intended to be set in motion by natural forces, Calder's mobiles express quite a different aspect of Kinetic art to the futuristic, mechanical contraptions of other artists. The element of chance or contingency introduced into the viewer's encounter with the piece by its interaction with the atmosphere might be described as post-Dada, but there is also a lyrical engagement with nature evident in this effect, and in the graceful organic curves of the piece, while something of the aura of the fine-art object is imbued by Calder's hand-crafting process. In its interaction with the natural world, Calder's work predicts post-Kinetic developments such as Light Art.

Painted and unpainted sheet aluminum, iron wire, and copper rivets - Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice, Italy

Vega III

Vega III, by the Hungarian-French artist and graphic designer Victor Vasarely, is an early example of what was later dubbed Op Art, a subcategory of Kinetic art which relies on the illusion of movement rather than actual movement - whether mechanical or natural - for effect. In an early example of a technique that would later become synonymous with his work, Vasarely uses a warped, black-and-white chequerboard pattern to create the illusion of convex and concave shapes within a flat picture-plane.

Vasarely had supported himself for several years as a successful commercial graphic designer before turning to painting after the Second World War, and many of the visual effects employed in his Op Art were first conceived with the advertising billboard in mind. In the early 1940s, with the curator Denise René, he co-founded the Gallerie Denise René on the outskirts of Paris, establishing it over the next few years as a hub of post-war developments in Kinetic and Op Art. Vasarely himself exhibited there from 1944 onwards, and the breakthrough group exhibition Le Mouvement, staged at the gallery in 1955, presented a clear and coherent survey of Kinetic art for the first time, placing Vasarely's work alongside that of predecessors such as Duchamp and Calder, and contemporaries such as Jesus Rafael Sotó and Jean Tinguely. The origins of Kinetic art, it seemed, extended back into the early twentieth century, while the style was currently in an exciting stage of growth. Vital to this impression, conveyed so successfully by the exhibition, was Vasarely's Manifeste Jaune or "Yellow Manifesto", published to coincide with the show, which sounded a new clarion call for abstract art in the wake of the Second World War, declaring that "pure form and pure color can signify the world".

Inspired by the Constructivist movement and the Bauhaus, Vasarely's mature work in a sense moved beyond Kinetic art before Kinetic art itself had even taken off as a style. In making the viewer's sense that the artwork was moving - rather than the actual movement of the artwork - vital to their engagement with it, Vasarely staged important new questions about the interplay of material form and subjective interpretation in defining the boundaries of the art object: movement could be a sensation entirely generated in the human brain, not necessarily dependent on any physical stimulus. Vasarely also brought a new, scientifically precise awareness of the physiological process of vision to Kinetic art, and inspired a generation of younger artists such as Bridget Riley.

Oil on canvas - The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, New York

CYSP 1

The title of CYSP 1, created by the French-Hungarian artist Nicholas Schöffer, is an abbreviation of "Cybernetics" and "Spatiodynamics". Designed in conjunction with the Phillips electronics company, CYSP 1 was a construction of black steel and polychrome aluminum plates mounted on a base with four rollers. In this base was set an 'electronic brain' which used photo-electric cells and a microphone to record variations in the light intensity, color, and sound levels in the sculpture's surrounding environment. Variations in these atmospheric factors triggered different types of movement: when the sculpture recognized the color blue, for example, it would move forwards, retreat, or turn quickly. Designed partly for use on the stage, CYSP 1 was incorporated into a performance given by Maurice Béjart's ballet company at the Festival of the Avant-Garde in Marseilles in 1956.

Many of the earliest works of Kinetic art had utilized mechanical movement as the basis of their time-bound element, and since the late 1940s Schöffer himself had been creating what he called "spatiodynamic" sculptures, equipped with electric motors allowing remotely-controlled movement. But the integration of an environmentally responsive, unpredictable element into that movement was a major step forward for Kinetic art. Schöffer was familiar with the new field of "Cybernetics" defined in Norbert Weiner's 1948 book of that name, which proposed that the behavior of both humans and machines was based on "feedback loops" established with external environments. Not only did this theory provide a model for artificial intelligence, but it also proposed that the intelligence of humans was no different from that of machines, and that, theoretically, thinking life-forms could therefore be constructed. CYSP 1 represents perhaps the first concerted application of this theory to modern art, and thus signifies a radical advancement in the conceptual and technical scope of Kinetic art.

If Kinetic art was split between those who saw the machine as humankind's potential savior and those who saw it as the potential source of its ruin, Schöffer's work from the 1950s onwards presents the more radical proposition that there is no clear distinction to draw between human and mechanical life in the first place. Through works such as CYSP 1, and more ambitious projects such as his Cybernetic Tower, installed in 1961 outside Liège Conference Centre, he used Kinetic art as the springboard for projects which blurred the boundaries between art and AI, ensuring the longevity and significance of the Kinetic art movement itself.

Painted steel and polychrome aluminum, rollers, electronic sensors and motor

Homage to New York (fragment)

Homage to New York was constructed over three weeks in the sculpture garden of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, with the assistance of several other artists and engineers including Robert Rauschenberg. On its first unveiling in March 1960, it set itself on fire and self-detonated over the course of a 27-minute display of noise and light (to the complete surprise of the assembled audience, and MOMA staff, who eventually called the fire brigade). 23 feet wide and 27 feet high, the sculpture itself was an assemblage of interlocking, mechanized found components, including pieces of scrap metal, wheels, bicycle horns, a piano, a bathtub, and a go-cart, all jutting out into space to create an entanglement of abstracted forms. The fragmented remains of the piece now form part of MOMA's permanent collection.

The Swiss artist Jean Tinguely represented the more anarchic wing of the post-1945 Kinetic art movement. Though his work was displayed alongside that of post-Constructivist compatriots such as Victor Vasarely at the genre defining 1955 show Le Mouvement, sculptural works with names such as Frigo Duchamp (1960) and Suzuki (Hiroshima) (1963) indicate the more Dadaish, socially polemical stance underlying Tinguely's output. He generally constructed his sculptures and machines - what he called his "metamechanical" works - from a bricolage of found objects; by setting them in motion, he performed witty visual commentaries on capitalism's tendency to generate endless, functionless production, often with destructive and violent side-effects. As a signatory of Pierre Restany's 1960 manifesto "Les Nouveaux Réalistes", Tinguely associated himself with a broader movement in French art towards happenings, process-based activities, and works of found sculpture and collage which tore down the barriers between representation and reality, with politically-charged intent.

Homage to New York presents a different idea of the relationship between human life and mechanization than the optimistic, post-Constructivist visions of other Kinetic artists, and thus represents an important and unique contribution to the style. For Tinguely, the rampant drive towards mechanization evident in modern consumer culture was a path towards catastrophe and death. In this sense, his concerns mirror those of Gustav Metzger and the 1960s Auto-Destructive Art movement, as well as those of his peers in the French Nouveau Réalisme movement, placing Kinetic art in a wider historical trajectory than that implied by its Constructivist heritage alone.

Mixed media including painted metal, wood, and rubber tires - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Blaze

The zig-zagging black and white lines of Blaze create the illusion of a vortex burrowing down into the centre of the picture-plane. As the brain plays with the image, the concentric rings - like a psychedelic Dante's inferno - appear to shift back and forth, suggesting inward, revolving motion as they curve rhythmically around the center of the page. Although the image is monochromatic, prismatic colors also appear, as the eye attempts to focus on the piece. Blaze is a brilliantly executed example of the subcategory of Kinetic art known as Op Art.

Its creator, the London-born Bridget Riley, had worked through various styles, including versions of Impressionism and Pointillism, before embarking from around 1960 on the visually mesmeric prints and paintings for which she is now known. Blaze is an early and quintessential example of her mature style, a work which defines the best of the Op Art movement, which was showcased the following year in the enormously successful MOMA show The Responsive Eye. That exhibition, whose catalogue featured Riley's 1964 painting Current on its cover, shot the artist to worldwide fame, and today she remains the best-known of the post-war Kinetic artists (an even more significant achievement given that, along with others such as Liliane Lijn and Vera Molnár, she was one of only a few women associated with the movement).

Blaze has been interpreted in relation to the Precision Optics and Roto-Relief series of Marcel Duchamp, while the black-and-white color-palette and vortex-like form also suggest an affinity with the Vorticist painter and camouflage designer Edward Wadsworth. Riley's work has also been seen to convey a fascination with bodily and organic rhythms, and with landscape painting in the tradition of Seurat: indeed, more than any other figure, Riley has been concerned - as both artist and curator - to show the origins of Kinetic Art in the painting styles of the late-19th century. Her work thus shows the depth of Op Art's historical roots, and, for this reason and because of its sheer technical brilliance, represents a vital contribution to the genre.

Screen print on paper - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Labyrinth

The Groupe de Recherche d'Art Visuel or GRAV, established in Paris in 1960, was made up of 11 Optic and Kinetic artists, including significant individual artists such as Julio Le Parc, Vera Molnár, François Morellet, Francisco Sabrino, and Jean-Pierre Yvaral (Victor Vasarely's son). For the Paris Biennale in 1963, GRAV constructed one of its various 1960s works known as "labyrinths", interactive mazes through which spectators were invited to walk, engaging en route with various effects of light-play and movement. The 1963 labyrinth involved light-sources placed behind perforated screens or arranged in sculptural shapes, wall-mounted reliefs, mobile bridges, and various other kinetic-sculptural elements arranged into twenty distinct environmental sections.

Influenced by Vasarely, artists such as the Argentinian Julio Le Parc - now perhaps the best-known of the GRAV artists - set about furthering his experiments in various respects. In integrating the effects of Kinetic art into walk-through environments, for example, the GRAV artists took the emphasis on viewer-engagement implicit in Vasarely's optical illusions one step further, literally inviting viewers into their artworks, and thereby encouraging highly subjective encounters with those works. The artists of GRAV, like the early pioneers of Kinetic art, also placed great emphasis on the potential social significance of their work, suggesting in their manifestos and critical statements - such as "Enough Mystification", published to coincide with the 1963 Biennale - that new forms of visual experience might herald new forms of collective cultural and social experience. By pooling their resources, and by placing emphasis on "research" rather than subjective inspiration, the group also emphasized the idea of collective intelligence over individual genius, another implicitly political gesture.

Though the activities of GRAV, like the Kinetic art movement in general, did not outlast the 1960s, their collective endeavors over that decade stand as one of the most significant monuments to the impact and widespread acceptance of ideas associated with Kinetic art during the 1950s-60s. Moreover, in moving from Kinetic to Interactive Art, the artists of GRAV predicted one of the many ways in which the ideas of Kinetic art would outlast the movement itself.

Temporary sculptural construction; mixed media

Beginnings of Kinetic Art

In its focus on capturing the dynamism of its subject-matter, Kinetic Art expresses a foundational concern of modern art in general, and many critics have cited Post-impressionist painters such as Seurat as the first Kinetic artists. But the first examples of modern artworks which literally incorporate movement - or movable elements - date from the 1910s, and were created by artists working in the Dadaist and Constructivist traditions. Arguably the earliest work of Kinetic art is the Dadaist Marcel Duchamp's Bicycle Wheel (1913), which consists of a wheel placed upside down on a stool; this is also recognized as the first readymade. In 1920, Constructivist artists Naum Gabo and Antoine Pevsner used the term "Kinetic art" in their Realistic Manifesto; the same year, Gabo completed his Kinetic Construction, a free-standing metal rod set in motion by an electric motor which articulates a delicate wave-pattern in the air, the first work of modern art primarily concerned with expressing movement. Ten years later, the Bauhaus artist László Moholy-Nagy used the term "kinetic" again, to describe the mechanized motion of his Light-Space Modulator (1930), while other figures associated with the Bauhaus, and with the post-Constructivist movement of Concrete Art, produced work across the 1930s-40s which might now be called Kinetic art.

Accepting these early expressions of the concepts underpinning Kinetic art, it was not established as a coherent movement until 1955, when the group exhibition Le Mouvement was held at the Galerie Denise René in Paris. Central to this show was the work of Hungarian artist and René Gallery co-founder Victor Vasarely, whose Manifeste Jaune ('Yellow Manifesto'), published to coincide with the exhibition, became one of Kinetic art's founding documents. Vasarely had been trained in the traditions of the Bauhaus, and had spent many years working in commercial design before turning to fine art, bringing with him various graphic techniques which would inform his new approach, including the use of grid-like arrangements of black and white to suggest depth or motion. Vasarely's work quickly attracted followers, most notably Bridget Riley, who would make a comparable range of effects world-famous.

Other works featured in the Mouvement show relied on real rather than implied movement. In some cases, this movement could be initiated by air or touch, as in the case of Alexander Calder, whose mobiles, including Arc of Petals (1941), combine graceful sculptural lines and biomorphic shapes with a responsiveness to atmospheric movement mimicking the natural behavior of organic forms in space. Or, as was more often the case, the movement could be mechanized. Nicolas Schöffer's interest in incorporating dynamism into his Constructivist-inspired sculptures initially resulted in ever more complex articulations of modelled space. But from the late 1940s he also introduced mechanized motion and theories from cybernetics into his work, producing "Spatiodynamic" sculptures whose movements were governed by environmental feedback.

Kinetic Art: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

The Legacy of Constructivism

The Kinetic art movement emerged out of what was widely perceived as the decline of geometric abstraction in the post-1945 period. Due to its origins in Constructivism - and in associated movements and schools such as De Stijl and the Bauhaus - geometric abstraction had initially been associated with revolutionary attitudes to art and society. Its austere compositional lexicon of lines and flat planes, and its simplified color palette, seemed to express the rationalizing impetus of the modern world, and to promise a new, universally coherent artistic language, while the philosophy that grew up around it was concerned with the integration of art into everyday life, and focused on applied artforms such as architecture and ceramics. These ambitions faded across the middle decades of the twentieth century, however - in line with the ambitions of Utopian politics - and by the end of the Second World War geometric abstraction was increasingly perceived as a somewhat outmoded, drily academic style.

The Kinetic art movement revitalized the tradition of geometric abstraction, utilizing mechanical or natural motion to establish new relationships between art and technology, and to forge new grammars of abstract composition which, it was once again felt, might transcend cultural and national boundaries. To that end, kineticism was introduced across several artistic media, including painting, drawing, and sculpture, and many Kinetic artists sought to work with ever newer and more public media in order to bring the style to a wide audience. Artists associated with a broadly Constructivist approach to Kinetic art include Naum Gabo, László Moholy-Nagy, Victor Vasarely, and Bridget Riley.

The Legacy of Dada

Kinetic art also drew heavily on the Dada movement, which had inspired some of the earliest works of modern art employing motion, such as Marcel Duchamp's Bicycle Wheel (1913) and Roto-Reliefs (1935-65). The motivation for such works, and for the Kinetic artworks inspired by them, was not so much an interest in uniting art and technology as a desire to break with the conventional constraints of the static artwork. Instead of the viewer's experience of the artwork being determined by the artist in advance, Kinetic artists made the movement of the work - and the viewer's subjective perception of that movement - a vital and necessarily unpredictable element of their encounter with it.

The post-Dada element in Kinetic art is partly responsible for the skepticism of technology as an expression of cultural progress which defined elements of the movement. Jean Tinguely, one of the artists exhibiting at Le Mouvement in 1955, expressed this skepticism most forcefully with his self-destructing sculpture Homage to New York (1960), an unwieldy mechanical contraption designed to set itself on fire, and to disintegrate in a hail of sound and light. Other artists associated with Kinetic art, such as Alexander Calder, were influenced by post-Dada and Surrealist artists such as Joan Miró, while Calder's interest in change, contingency, and biomorphic abstraction arguably place in the Dadaist wing of the movement.

The Influence of Science

The Constructivist tradition had always been inspired by a technological conception of life, and this was especially evident in the work of the Kinetic artists influenced by it, many of whom borrowed concepts from fields such as physics, optics, and cybernetics. Naum Gabo's Kinetic Construction (1920), arguably the prototype for all subsequent Kinetic art, was designed to express the concept of the "standing wave" - a type of wave-motion which creates the illusion of a static, curvilinear form - while the Op Art pioneer Victor Vasarely based his visual tricks on studies of the ocular perception of line and color. In broader terms, new conceptions of the relationship between time and space, established by the work of theoretical physicists such as Albert Einstein, provide the ambient cultural context for the fascination with movement evident in Kinetic art.

The interaction of science and Kinetic art was arguably most strikingly expressed by Nicholas Schöffer's "Spatiodynamic" sculptures of the 1940s-50s, intelligent machines whose movements and physical activities would alter based on changes in their external environment. These works were influenced by the newly established field of cybernetics, which posited a series of analogies between human and artificial intelligence. As such, Schöffer's work pushed the integration of science into art to its logical conclusion, implying that human behavior itself might be no more than the expression of a mechanical process.

Later Developments - After Kinetic Art

The mid-1960s brought considerable acclaim to Kinetic works and artists. Julio Le Parc, a pioneer in interactive Kinetic art, was awarded the Grand Prize for Painting at the Venice Biennale in 1966, and Nicolas Schöffer won the prize for sculpture in 1968; the Galerie Denise René celebrated ten years of Kinetic art in 1965 with a group show entitled Le Mouvement 2. But it was increasingly felt that Kinetic art had ceased to be aesthetically or politically radical, and was being steadily incorporated into the art establishment. Arguably, and ironically, the deathblow for Kinetic art was the huge popularity of The Responsive Eye, an exhibition focusing on the Op-Art wing of the movement, held at the The Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1965. The very definitiveness of this exhibition perhaps presented Kinetic art as something of a fait accompli, while some critics criticized the work on display as mere 'gadgetry', a collection of kitsch optical tricks whose only value was in momentarily titillating the eye.

By this time, however, the pioneering generation of kinetic artists had already inspired a number of other artists and collective endeavors, whose work would help the ideas underpinning Kinetic art to survive the demise of the movement itself. In Paris, in the 1960s, the Groupe de Recherche d'Art Visuel (GRAV), inspired by Vasarely's ideas, created various immersive, multi-sensory sound-and-light environments, heralding a move towards the post-Kinetic Interactive Art of the following decades. In California, during the same period, the Light and Space Movement, also influenced by Kinetic art, as well as Minimalism and Conceptual Art, pursued the interest in organic movement and natural visual effects which had defined one wing of the Kinetic art movement.

A vast range of individual artists have employed movement in their work in one way or another since the 1960s, some of them influenced by Kinetic art, and almost all of them by the same principles that informed the movement. Rebecca Horn's sculptures often fuse elements of Dada, Fluxus, and Kinetic aesthetics; her Concert for Anarchy (1990) features a grand piano suspended upside down from the ceiling, from which, every few minutes, the keys are thrust out. The North-American artist Liliane Lijn - one of the first artists to incorporate text into kinetic sculpture, with her poem-cones of the 1960s - combined kinetic sculpture with feminist mythography in the construction of her animatronic Conjunction of Opposites (1986). The playground slides, carousels, and interactive sculptures created since the 1990s by Carsten Höller owe little to Kinetic art directly, but the incorporation of bodily movement into the work is obviously vital to their effect. Today, then, the Kinetic art movement perhaps seems less a direct influence on artists than the source and manifestation of some of the most ubiquitous ideas in contemporary art.

Useful Resources on Kinetic Art

- Force Fields: An Essay on the KineticOur PickBy Guy Brett, Marc Nash

- Kinetic Art: Theory and PracticeBy Frank J. Malina

- Origins and Development of Kinetic ArtBy Frank Popper, S. Bann

- Robert Rauschenberg & Jean Tinguely: CollaborationsBy Roland Wetzel, Mari Dumett, Robert Rauschenberg, Jean Tinguely

- Alexander Calder and His Magical MobilesBy Jean Lipman, Margaret Aspinwall

- Victor Vasarely: 1906-1997; Pure VisionBy Magdalena Holzhey

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI