Summary of John Russell

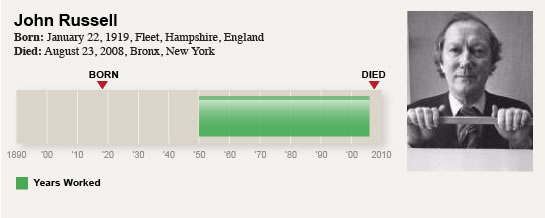

John Russell was an art historian and critic who wrote for the London Sunday Times from 1950-1974, then for the New York Times from 1974-1990, coming on board immediately after the departure of John Canaday. Although seldom cited in the annals of Abstract Expressionist history, Russell's work as a critic was crucial to the continued enthusiasm for modern art well into the 1970s and 80s. Known paradoxically as a tough-minded critic who was nevertheless, perhaps a little too lenient when it came to newer movements in art, Russell wore two masks as an art critic: He was a champion of newer, younger artists like David Hockney and Howard Hodgkin, and was also an accomplished scholar of the Impressionists and subsequent modern movements. Key Ideas / Information

- Russell did not believe that genius was an innate quality; rather it was a quality that was nurtured and educated. All great works of art may only come about once the artist has studied and evolved over time.

- When new art forms arrive, many consider them replacements for the old, but for Russell, this simply was not the case. Any new worthwhile artwork is directly influenced by its predecessors, and it was new art, more than anything else, that kept the Old Masters alive and relevant.

- When it came to art criticism, Russell believed that every artist, no matter what their medium or technique, is worthy of receiving the same degree of attention and diligence in a review. While some work is naturally better than others, Russell was never mean-spirited in any of his writings, even if a work of art wasn't in his favor.

Childhood

Raised by his grandparents in London, Russell attended St. Paul's School and then moved on to study philosophy and economics at Magdalen College at Oxford, where he earned his B.A. in 1940. Early years

Russell was interning at the Tate Gallery when the Germans bombed London during the Blitzkrieg of 1940. He was then evacuated to the country town of Worcestershire. Between 1942 and 1945, Russell served in the British Admiralty for the Naval Division. While serving, Russell met the author and journalist Ian Fleming (famous for creating the James Bond novels), who recommended Russell to the London Sunday Times as a book reviewer. Now with the Sunday Times, Russell began his career as a professional critic, covering not only books but also art, theater and music.

Middle years

In 1950, the art critic for the London Times was fired for writing a negative review of an exhibition at the British Royal Academy, and Russell was subsequently promoted to chief art critic. That same year, he also became a corresponding art critic for the New York Times.

In 1950, the art critic for the London Times was fired for writing a negative review of an exhibition at the British Royal Academy, and Russell was subsequently promoted to chief art critic. That same year, he also became a corresponding art critic for the New York Times. During the 1950s, Russell took on a diverse and vast amount of writing assignments, and published several books, including a travel book on Switzerland in '50, a biography of the classical Austrian conductor Erich Kleiber in '56, and a history of the city of Paris in 1960.

Between 1958 and 1968, Russell sat on the art panel of the Arts Council of Great Britain. During this time, the critic played an integral role in curating several exhibitions, including three at the Tate in London (Modigliani, Rouault, and Balthus), and one at the Hayward Gallery in London (Pop Art Redefined).

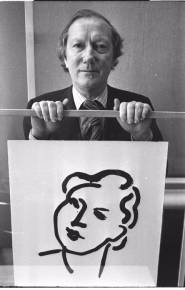

In 1965, Russell wrote a book on Seurat, which many consider to be his best work. A few years later, in 1971, Russell oversaw a traveling exhibition devoted to Vuillard that went from Toronto to Chicago and ended in San Francisco.

In 1974, Russell was recruited by the New York Times chief art critic Hilton Kramer (who had replaced John Canaday) to move to the U.S. and become a resident art critic. Russell would later become the chief art critic in 1982, a position he held until 1990.

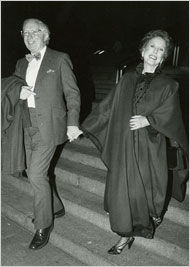

In 1975, Russell got married (for a third time) to Rosamond Bernier, an art critic and editor for the Paris magazine L'Oeil, who had recruited Russell to write for the magazine back in the mid-50s. They were married in Philip Johnson's famous Glass House in New Canaan, CT. Pierre Matisse (Henri's son) was the best man, and Leonard Bernstein wrote the wedding march.

Later years and death

Russell may have left his chief critic post at the New York Times in 1990, but this was no retirement. He continued writing for the New York Review of Books, as well as several guest reviews for the Times. Between 1981 and 2006 Russell edited the Century Bulletin on behalf of The Century Association, a New York organization of some two-thousand authors and artists.

He died in a Bronx nursing home in 2008 at the age of 89.

Legacy

Russell was not well-known for his prowess as an art historian or scholar, but his work as a critic and author suggest a vast catalogue of knowledge, not to mention an undying appreciation for art in all its forms. He had the unique ability to look at something and instantly know who and what inspired the artist. As a writer, he was quick-witted, elegant and extremely learned, and above all, he communicated the message that all great art is connected by its ability to give generation after generation a sense of who they are. Russell was remembered by artists and other art writers as someone who paid very close attention to the smallest of details and the grandest of visions and, according to the artist Howard Hodgkin, he "was very determined to make his own criticism as valuable as possible, which meant never selling an artist short by conferring easy or less than deserved praise on his work."

THEORY:

Intro to Russell's Art Theory

Much like Baudelaire in 1840, Russell recognized that in his time, new art was being produced at an ever-accelerating rate. As the modern world continued racing ahead, people discovered new needs, and many turned to art to meet those needs. Russell wrote: "In art, equally, we had needs which could not be satisfied by the Old Masters, because those needs did not exist when the Old Masters were around." While there are critics who inevitably reach an end-point where all new art ceases to appear relevant or even good, as was the case with Harold Rosenberg and arguably Robert Hughes, Russell was quite different. For all the greatness of the Old Masters, he felt obliged to appreciate new art because, as history had taught him, when there's a need that can only be satisfied by the beauty of a Munch or Kandinsky, looking at a Manet simply will not do. Russell on America and New York City

Like the rest of the art world, Russell clearly saw that no uniquely American art movement had been able to sustain itself prior to 1945. But what fascinated the critic was just how America redefined itself in terms of the arts and modernism after World War II. Russell looked deep into American cultural and literary lore to find the roots of modern art, citing Thoreau's Walden, Whitman's Leaves of Grass, Eliot's Wasteland, and the various writings of Poe, all as chief precursors to the modern visual revolution that came about in the mid-20th century. In the section of his book The Meanings of Modern Art entitled America Redefined, Russell wrote: "It would have been difficult, in any case, for American painters to rival the epical assurance with which both Whitman and Melville addressed themselves to an expanding America." What changed all of this, in Russell's view, was New York City's arrival as the capital of modern art production, for both native-born Americans and people like himself; emigrants who flocked to New York to become part of the burgeoning art world. "There are," wrote Russell, "as many New Yorks as there are New Yorkers. New York is a self-devouring, self-renewing city, with which we come to terms as best we can. It is one of the supreme subjects of our century: one for which we would wish Balzac, Dickens and Proust to have been born again."

Russell on Action Painting

Russell didn't believe that Action Painting's arrival as a leading American art form was merely a coincidence, nor did he completely share Harold Rosenberg's view that it was the product of improvised action from the artist's unconscious (a belief that led many to conclude Action Painting was melodramatic and self-indulgent). Russell looked further back in time to pinpoint Action Painting's relevance. "It arose from an intelligent examination," wrote Russell, "on the part of people who had been serious artists for nearly half a lifetime, as to just why so much of European painting had run itself into the ground. And it stood for an idea current in public life also: that human nature had not said its last word." In the paintings of de Kooning, Rauschenberg, Still, and others, Russell shared Rosenberg's view of Action Painting's evolution. These images were "generated by the very act of applying the paint, without conscious reference to anything in the world outside the studio and with concessions to the divide which once separated painting from drawing, foreground from background and light from shadow." But Russell firmly believed there was something learned and psychologically profound in these images; an expressive force that had sprung out of years and years of studying Kandinsky, Klee and Léger.

Russell on Abstraction and the "New York School"

Russell wrote of the Abstract Expressionists: "To speak of them as 'a school' is a matter more of convenience than of historical truth. Yet one thing was common to all of them, and common to most thinking people in the late 1940s: a feeling of 'either/or.' In art, as in so many other departments of life, humanity was being given a fresh start. It was time to stand up and be counted; the question at issue was (or seemed to be) either a decisive shift in sensibility or a genteel continuance."  Russell was not content to group artists like Johns and Rauschenberg with others like Pollock and de Kooning. He saw greatness in all their works, but believed it inaccurate to place them in the same movement or "school." Whereas the so-called Action Painters (Pollock and de Kooning) had supposedly blocked out the world outside the studio in order to work their canvases, there were others who welcomed the world into their work. In writing about Rauschenberg, Russell said: "He saw it as the function of the artist to work with what is given; and in paintings .. he sieved the dredged filth of New York City as a prospector sieves the sand of the riverbed: for gold."

Russell was not content to group artists like Johns and Rauschenberg with others like Pollock and de Kooning. He saw greatness in all their works, but believed it inaccurate to place them in the same movement or "school." Whereas the so-called Action Painters (Pollock and de Kooning) had supposedly blocked out the world outside the studio in order to work their canvases, there were others who welcomed the world into their work. In writing about Rauschenberg, Russell said: "He saw it as the function of the artist to work with what is given; and in paintings .. he sieved the dredged filth of New York City as a prospector sieves the sand of the riverbed: for gold." Russell on post-Abstract art

As Pop art made its way onto the scene in the late 1950s, Russell saw yet another new occasion for optimism in American modern art. In his writings on Warhol, Lichtenstein and Rosenquist, Russell said, "There was in Pop art an element of exorcism. It was made to banish evil memories, or to hoist them to a level on which they would lose their power to degrade." But Russell's optimism stretched far beyond the boundaries of Pop or Op art. He was always excited by how modern art constantly reinvented itself, and found new ways to draw from historical influences, yet avoided becoming tired and repetitive. New experiments in the application of space and color (found in the works of Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland), and the use of new instruments in art (installation, landscapes, found objects, etc.) were all things that motivated the critic to keep writing and praising art as modernism faded and postmodernism arose, long after the writings of critics like Greenberg and Rosenberg had ceased being relevant.

In particular, Russell was a huge champion of David Smith, who the critic claimed "may have been the last major artist to have an absolutely explicit, constructive and sanguine conception of the future of art." While it's true that Russell appeared to have loved just about everyone (in reality this is an overstatement), he reserved his greatest praise for those select few who represented the complete artist; one who embodied the past, present and future of Modern art.

Writing style

Russell was revered for his talent as a natural writer. He wrote in a very persuasive, witty tone that his readers found comforting and relatable. Unlike his Times predecessor, John Canaday, Russell was not a controversial writer. In fact, some have criticized Russell for being too accepting of most forms of Modern art, and not being critical enough. (There are moments while reading Russell when one may get the impression that he liked just about every work of art he came in contact with.) But the supposed mystery behind Russell's ubiquitous praise was his very keen eye, and a mind that seemed to be its own reference library. Whenever he looked at something, it seemed as though he accessed a dozen or so other works of art. He saw influences right away; nothing was without precedent. Writing in a rhythmic and elegant style that is reminiscent of Gertrude Stein or his fellow countryman Roger Fry, Russell's primary objective in his writing wasn't to promote the arts that were already popular, but to draw well-deserved attention to some of the lesser-known artists in whose work he saw great potential.

ARTISTIC INFLUENCES

Below are Canaday's major influences, and the people and ideas that he influenced in turn.

ARTISTS

J.M.W. Turner

Georges Seurat

Edward Hopper

Stuart Davis

Wassily Kandinsky

CRITICS/FRIENDS

Honore de Balzac

Henry James

Charles Dickens

Clement Greenberg

Harold Rosenberg

MOVEMENTS

Impressionism

Post-Impressionism

Art Nouveau

Cubism

Surrealism

Years Worked: 1950 - 2006

ARTISTS

David Hockney

Howard Hodgkin

Anselm Kiefer

Philip Guston

Jeff Koons

CRITICS/FRIENDS

John Richardson

Lewis Hyde

T.J. Clark

Robert Rosenblum

MOVEMENTS

Conceptual Art

Minimalism

Quotes

"Art in New York was one of the driving, generative forces in the city's cultural life." "It is the highest function of art to tell us who we are."

"Modernism is not something that can be learned step by step, like bookkeeping."

"I think that art should be allowed to go private. It should be a matter of one-on-one. In the last few years, the public has only heard of art when it makes record prices at auction, or is stolen, or allegedly withheld from its rightful owners. We need to concentrate more on art that sits still some place and minds its own business."

"It is difficult in the United States of America to make a mystique of something that has neither social status nor academic status and doesn't make any money."

Content written by:

Justin Wolf

Justin Wolf

THIS PAGE IS OLD

The Art Story Foundation continues to improve the content on this website. This page was written over 4 years ago, when we didn't have the more stringent/detailed editorial process that we do now. Please stay tuned as we continue to update existing pages (and build new ones). Thank you for your patronage!

IMPORTANT ARTWORKS:

|  |  |

|  | |

| FEATURED BOOKS: Written by Russell  The Meanings of Modern Art The Meanings of Modern Art  Reading Russell: Essays, 1941-1988, On Ideas, Literature, Art, Theater, Music, Places, and Persons Reading Russell: Essays, 1941-1988, On Ideas, Literature, Art, Theater, Music, Places, and Persons  London London  Matisse: Father and Son Matisse: Father and Son RESOURCES: Articles by Russell: Articles about Russell: |

Ask The Art Story AI

Ask The Art Story AI